On the time Stevenson was first creating Nimona, he was not but out, to himself or others. It was earlier than he got here out as homosexual and earlier than he got here out as transmasculine. He wrote Nimona to be a gender-nonconforming character, but in addition as an influence fantasy to flee his discomfort together with his physique: “I was very uncomfortable in my body, and I was moving through the world. I just wanted to be her. To be able to change at a moment’s notice to be a dragon, to breathe fire, all of these things.”

It’s not a coincidence that Nimona—within the e book and film—incessantly takes on male personas. There was trans subtext within the story from the beginning, however Stevenson wouldn’t name it that:

“Subtext implies I knew what I was doing… calling it subtext is generous, because that implies that I was doing any of that on purpose. I really, really did not put it together.”

In different interviews, Stevenson says, “It’s (transness) something that I think is at the heart of the comic, but I didn’t know it at the time. It would be many years before I’d start to make any kind of sense of my own gender.”

In making the film, Stevenson was in a position to see the queer and trans components of the story that he didn’t acknowledge on the time: “I was so not ready to feel that, and I didn’t know that was the story I was telling.”

“But I’m not a girl. I’m a shark.”

Nimona isn’t essentially canonically queer or trans within the film, both, however the trans subtext is rather more pronounced than it’s within the e book. I misplaced monitor of what number of traces there have been within the film which have trans subtext, however listed below are a couple of:

“So you’re a girl and a rhino?” “I’m a lot of things.”

“What are you?” “I’m Nimona.”

“Can you just be you, please? “I don’t follow.” “Girl you.” “But I’m not a girl. I’m a shark.”

“Can you just be normal for a second?” “Normal?” “I just think it would be easier if you were a girl.”

“And now you’re a boy.” “I am today.”

It’s value noting that Ballister is normally the particular person saying these invalidating issues to Nimona. He’s the closest particular person in her life, and their relationship is extra developed than it’s within the e book—however that makes his betrayal hit more durable.

In an interview with Stevenon for Off Color, Sydney Turner says, “When I watched Nimona, I thought about how transphobia in the queer community is at large, how sometimes cis gays, like Bal, try to fit into corrupt systems and institutions that the trans community, like Nimona, can’t, no matter how hard they try.”

It’s a model of homonormativity: whereas Ballister is queer, he nonetheless upholds the dominant values of the society he was raised in, and he needs to evolve. He resents Nimona for refusing to decrease herself. He calls her “too much.”

When Ballister insists on asking what she is, Nimona calls these kinds of inquiries “small-minded questions.” She explains that it doesn’t harm to rework; actually, she seems like she has “itchy insides” when she doesn’t, which could be learn as consultant of gender dysphoria. “I shapeshift and I’m free,” she says.

In Heather Wright’s Grasp’s Thesis, “’The Childish, the Transformative, and the Queer’: Queer Interventions as Praxis in Children’s Cartoons,” the writer factors out that “This question of Nimona’s ‘natural form’ evokes Judith Butler’s theories on gender”: it’s all performative and a development. There is no such thing as a one true kind for Nimona; she is a lot extra difficult than that.

It’s not simply Nimona’s fluid relationship together with her id and kind that makes her story, particularly within the film, a trans allegory. She additionally faces related bigotry to trans individuals.

“And I’m the monster?”

The world of Nimona might settle for romantic relationships between males, nevertheless it’s hardly a tolerant society. Residents stay in a metropolis surrounded by a wall, supposedly besieged by “monsters”—no less than, that’s what the individuals in energy declare, to justify their surveillance, weaponry, and military/police pressure.

In each the e book and the film, there’s a class divide: in a single memorable web page of the comedian, a person makes an attempt to sleep below the statue of Ambrotius Goldenloin, solely to be instructed by a knight to maintain shifting. Within the film, Ballister is the primary commoner to be allowed to coach as a knight—which the Director sees as a menace to the dominion: the “first crack in the wall.”

Even after Ballister is framed for regicide, even when he learns it was the Director who framed him, he insists that the Director is only a dangerous apple as an alternative of acknowledging the issues with the institute as an entire. Nimona pushes again, saying now could be the time to query every thing.

When discussing the science fantasy, futuristic medieval setting of the film, Stevenson says, it “feels very true to our world today, where it’s like we have all this advanced technology, but in some ways, you know, we’re still kind of bound by this medieval way of thinking.”

It’s this medieval mind-set, and the system that reinforces it, that’s the actual villain of the story. Children on this kingdom develop up on breakfast cereal commercials that encourage them to slay monsters. Nimona’s childhood pal, Gloreth, initially accepts her shapeshifting, however she is persuaded by her neighborhood to activate her and label her a monster.

When Nimona saves a baby who then picks up a sword, factors it at her, and calls her a monster, she tells Ballister,

“Kids. Little kids. They grow up believing that they can be a hero if they drive a sword into the heart of anything different. And I’m the monster? I don’t know what’s scarier. The fact that everyone in this kingdom wants to run a sword through my heart… or that sometimes, I just wanna let ’em.”

Nimona has grown up in a society that labels her a monster, isolates her, and considers self-defense justification for attacking her within the first place. That traumatization involves a head when even Ballister betrays her, calling her a monster and shifting to attract his sword on her.

As Heather Wright explains,

“By pulling his sword, Blackheart isn’t only engaging in micro-aggressions against Nimona, who has shown she is willing to let these pass without too much suffering, but is now automatically re-engaging in Nimona’s abuse (preparing to slay the monster). Furthermore, this moment drives home the role of state-sanctioned abuse as a primary factor in interpersonal abuse. This new injury causes Nimona to experience a flashback: a trigger to bring Nimona back to the full force of trauma at the initial moment of abuse. In this manner, Blackheart, Nimona’s only family, abuses Nimona with not just his own anger, but with the full power and force of the dominant cultural hatred of ‘monsters.’”

In his interview with Off Color, Stevenson says he sees now that transness is on the coronary heart of Nimona’s story, however in the middle of making the film, “I don’t think any of us expected how timely it would end up being.”

Trans persons are being villainized now greater than when Nimona was first created. Sadly, many trans younger individuals can empathize with being ostracized, hated, thought-about a menace—and even being labelled as monstrous.

In that very same interview, Stevenson compares the film’s fear-mongering about monsters lurking in all places to latest anti-trans laws.

It’s this systemic bigotry that overwhelms Nimona in that climactic scene of the film, and as she transforms into the monstrous, shadowy determine she feels others see her as, she makes an attempt to finish her personal life on the sword of Gloreth, the one who first betrayed her, rejected her, and referred to as her a monster.

Due to the science fantasy setting and imagery, it’s straightforward to lose sight of what’s taking place on this scene: a personality coded as a trans younger particular person is trying to kill themselves after society and household rejection.

Suicide charges are a lot greater amongst trans younger individuals than their cisgender friends. As Heather Wright factors out, this isn’t as a result of they’re trans. It’s due to the bigotry and abuse they usually face: “calling ‘queerness’ itself a risk factor is covering the source of abuse: social abuse and disenfranchisement based on the outsider status of the queer child.” Trans younger people who find themselves accepted by no less than one particular person of their life present a lot decrease charges of suicidality.

We see this acceptance on the finish of the film, as Ballister realizes he was unsuitable. He holds out a hand to Nimona in her shadowy kind and says, “I see you, Nimona. And you’re not alone.” It’s this second of acceptance that brings her again to herself.

“I’ve killed people before. I’ve killed LOTS of people.”: Queerness and Blurring of Boundaries in Nimona (2015)

Whereas the film provides a canon romantic relationship between Ambrotius and Ballister in addition to extra developed trans subtext in Nimona’s character, it additionally sacrifices loads of the complexity, sharpness, and boundary-pushing of the unique. As Heather Wright says, it’s the “blurring of boundaries” that undermines corrupt establishments, and Nimona (2015) has no easy binaries.

The binaries the e book targets most intently are good/evil and hero/villain. Within the film, Ballister rejects the label of villain. He was framed and has by no means actually finished something unsuitable. Within the e book, although, he has embraced the villain label. He lives by his personal ethical code, however he does issues—like non-fatally poison individuals to make a degree—that actually aren’t heroic.

Ambrotius’s character often is the most modified between the e book and the film. Ebook Ambrotius is egocentric, ultimately admitting to severing Ballister’s arm in an act of jealousy whereas colluding with the Director. Within the film, Ambrotius additionally cuts off Ballister’s arm, however solely as a result of he believes Ballister has simply killed the queen and is a menace.

Nimona, too, is a gentler character within the film. It’s aimed toward a youthful viewers than the e book, in order that is sensible, nevertheless it’s value noting that e book Nimona does homicide individuals. Ballister has to persuade her to not casually kill individuals when appearing as his sidekick.

Close to the top of the story, she is captured and experimented on. When she breaks free, she is consumed together with her anger, and Ballister fears what she may do on this state. As a Time article describes this second, “when Nimona is pressed to her breaking point, she splinters into two beings: a child that embodies all of the pain and betrayal she’s experienced and a creature of shadow and flame that personifies a blind rage toward the way she’s been treated.”

Ballister’s concern of Nimona at this second and what she’s able to isn’t irrational. She tells him, “I’ve killed people before. I’ve killed LOTS of people.” We see baby Nimona kill the invaders who attacked her village. We see present-day Nimona incinerate the Director. Ultimately, Ballister—the closest factor Nimona has to household—kills her creature self and leaves her baby self behind because the lab self-destructs. Ballister spots her alive within the closing few pages of the story, however their relationship continues to be severed, and that’s the final time he sees her.

It’s a bleak ending, nevertheless it was initially even darker. Stevenson says that this ending modified “for two reasons. The first was that I told my sister the ending and she threatened to never speak to me again if I didn’t change it. And two, I was also starting to get to the place, personally, where I was able to listen and say, ‘you’re right.’ The ending I had planned hasn’t felt right for a while. I think that the ending I had planned was an inability for me to imagine a happy outcome for myself.”

In Nimona (2015), nothing is easy, clear-cut, or binary. All of the characters are deeply flawed and harm one another. We cheer for Nimona, however she’s additionally a assassin. We wish Ambrotius and Ballister to reunite, even when Ballister did one thing unforgivable. We wish Ballister to get a contented ending regardless of betraying Nimona.

This isn’t “good queer representation” in the way in which it’s normally outlined. These characters aren’t position fashions. They’re one thing extra uncommon, and extra vital. They expose the uncomfortable messiness of being an individual. Typically, we could be monstrous. We could be deeply flawed. We make errors that may’t be totally repaired. And even then, we’re worthy of affection. As Stevenson says, “…that is really important to me: No one is lovable all the time. Everybody needs that understanding. And [Nimona] expresses that in a way that the rest of us can’t, not being able to turn into fire-breathing dragons.”

Nimona (2015) exhibits us characters we root for even once they’re egocentric, unsuitable, or monstrous. It provides a chance of loving ourselves even in our rage, even once we’re monstrous.

Along with the complicated and flawed characters, the e book additionally has an unpredictable plot. That is partly the liberty that webcomic as a kind permits: every web page is episodic, and the story is written over an extended time period, permitting it to evolve over time and zag in sudden methods. The film, in distinction, follows extra predictable story beats.

If we take a look at simply the ending, the 2 variations of this story method it in very alternative ways. Nimona is self-sacrificing as an alternative of rageful. Whereas I used to be moved by Ballister reaching out for Nimona and telling her he sees her, the subsequent scene was irritating.

The Director has aimed an enormous gun inside the town partitions to destroy Nimona, which might additionally kill many residents. After Nimona returns to herself, she transforms right into a phoenix-like creature and flies in direction of the gun, absorbing the affect, saving the town residents, and breaking open the wall to disclose a stupendous panorama behind it.

Within the aftermath, the residents assemble a memorial to Nimona, calling her a hero. Within the closing scene of the film, we see Ballister react to what appears to be Nimona’s return.

That is clearly imagined to be a contented ending—no less than, a happier ending than the e book. However given how Nimona is coded as trans, or no less than as The Different, it was uncomfortable to see her sacrifice herself to avoid wasting the identical individuals who terrorized her, who referred to as her a monster, who rejected her, traumatized her, and drove her to wish to finish her life.

After all, Nimona being functionally immortal makes this sacrifice much less closing, nevertheless it nonetheless feels unfair that the one means she may persuade the overall inhabitants to simply accept her as worthy was to threat her life for the individuals who hated her.

(That is principally the plot of “Rudolph the Rednose Reindeer:” the outsider is rejected till they save the day, after which everybody accepts them and the outsider holds no grudge for his or her earlier cruelty.)

As Heather Wright notes, even on this completely satisfied ending, the nod in direction of systemic change falls flat:

“[N]o ‘monster’ children are in this happy new world, or at least they are not visible in this moment. There’s no ‘home for battered monster girls’ opening in the main street. The new leadership or government systems are utterly unaddressed. And that knight is still there, even though they are playing ball with happy children. Is there evidence here that if another strange being arrives they will meet with kindness and welcoming? Have the police force (the knights) been adequately reformed in the ambiguous time since the film’s climax?”

However 2015 is a distinct time from 2023 (or 2025). As Wright says, “It might be that 2023 does not have space for the nuanced, messy, and very personal telling of Nimona that 2015 had.” The message has been simplified, its jagged edges smoothed: by the top of the film, Nimona has flipped from being seen as a villain to being seen as a hero, which doesn’t deconstruct that binary.

Maybe, in these instances, we’d like a gentler and kinder model of this story—particularly one aimed toward a youthful viewers. Stevenson says whereas adapting the story to the display, he “wanted to keep that darkness and that anger, but over the years I realized that while it’s easy to be cruel to yourself it’s much harder to be cruel to other people” and that’s wasn’t truthful to say there’s no completely satisfied ending for Nimona when so many individuals see themselves in her:

“[I]t would be irresponsible to present an ending without hope. Compared to the comic, which I think was hopeful in its own way, I think the movie takes a much more aggressive stance with that radical hope and love and acceptance.”

The graphic novel’s ending is ambiguous, purposely irritating and messy. It’s bittersweet. It’s comprehensible that on this political local weather, that ending was modified to be kinder to its characters—and to the viewers who see themselves in these characters.

“We are all, in our own ways, a question without an answer”: Why We Want Nimona Extra Than Ever

The e book and film provide very completely different views on the story, and I believe they work finest in live performance. The e book is extra spiky, sudden, and difficult—however the film, to me, has extra coronary heart. The unique Nimona leans cynical, whereas the film is hopeful. And whereas the plot is simplified within the film, it’s additionally—let’s be trustworthy—a bit clearer and paced higher.

I extremely advocate each the e book and the film, so you may get each points. However whereas they differ lots from one another, there’s one thing they share, and I believe it’s the magic of this story. It’s Nimona, in fact.

Nimona is much less murderous within the film, however she’s nonetheless herself. Whereas I’ve mentioned the trans subtext within the film, I’ve to make it clear that she’s not merely a stand-in for queerness or transness. Sadly, queer and trans individuals can not shapeshift into pink rhinos or cereal-spewing dragons or birds made from pure gentle (until I missed that day in orientation).

She’s not only a metaphor. She’s complicated, multi-layered, and unattainable to pin down. Ballister retains asking her, “What are you?”, and Nimona refuses to offer a easy reply, to scale back herself to one thing he (or anybody) can comprehend. We get a number of origin tales for Nimona, some clearly made up, some that could be true—or might not, or could also be solely a part of the story. None of them satisfactorily solutions the query “What are you?”, as a result of that may be a small-minded query.

As Stevenson places it in an interview for Out,

“She’s so often questioned like, ‘Everyone would be more comfortable, everyone would understand more if you tried to do something that was more palatable or more digestible for people who don’t get it.’ And that’s something I think that queer people deal with all the time: how to turn yourself into the most socially acceptable version of yourself so that you receive the love and acceptance that everyone needs.

It’s very radical to refuse that, to refuse to simplify yourself down or sand your own edges off or try to fit into some kind of framework that makes you make sense to other people. And I think that Nimona, she refuses to do that.”

Nimona isn’t merely misunderstood. In spite of everything, she does kill individuals. She is extra difficult than that. She rejects any pat means of understanding her. The truth is, understanding her is pointless and certain unattainable.

In an interview with Off Color, Stevenson reiterates this message on the coronary heart of the story:

“I just really want people to take the message from this movie. Even if you don’t understand every single aspect of someone’s identity, how they move through the world, or their experience, that you don’t need that in order to love them. You don’t need that in order to accept them. And when you really get to know someone, that understanding will start to come but you don’t need it. The first thing you need to do is love somebody.”

Many people can relate to feeling unattainable to utterly perceive: “We are all, in our own ways, a question without an answer. I think a lot of us feel that way, and I want to tell stories about that.”

On this time of elevated villainization of trans individuals, when politicians drum up an ethical panic towards trans individuals to get votes irrespective of the associated fee, it’s this message that’s strongest, and it persists by way of the e book and the film: you don’t want to know somebody to simply accept them and love them.

Whereas the story has remodeled over time, and a few components have been smoothed over, the explanation it persists is Nimona. She is essentially the most boundary-pushing factor—her refusal to be simplified and totally understood. She is defiant, uncontainable, rebellious as a matter in fact, and we’d like her greater than ever.

Nimona is aware of the right way to all the time query authority, rewrite dominant narratives, and be ungovernable. In a time of rising authoritarianism and fascism, she’s the hero (or villain or sidekick or not one of the above) we may all stand to take some inspiration from. She’s the explanation we fell in love with the graphic novel ten years in the past, and we’d like her greater than ever as we speak.

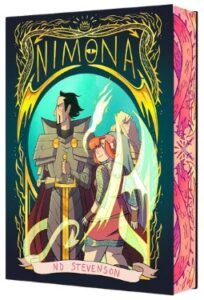

Psst, do you know the Nimona tenth Anniversary Version comes out Might twentieth? This isn’t sponsored; I simply thought you may want an version with a brand new cowl illustration, embellished edges, and bonus content material. It’s restricted, so seize one earlier than they’re gone.