Laura Winters, writing in The New York Times in 1996, called “Paradise” “a shimmering, oblique coming-of-age fable,” adding that “Admiring Silence” was a work that “skillfully depicts the agony of a man caught between two cultures, each of which would disown him for his links to the other.”

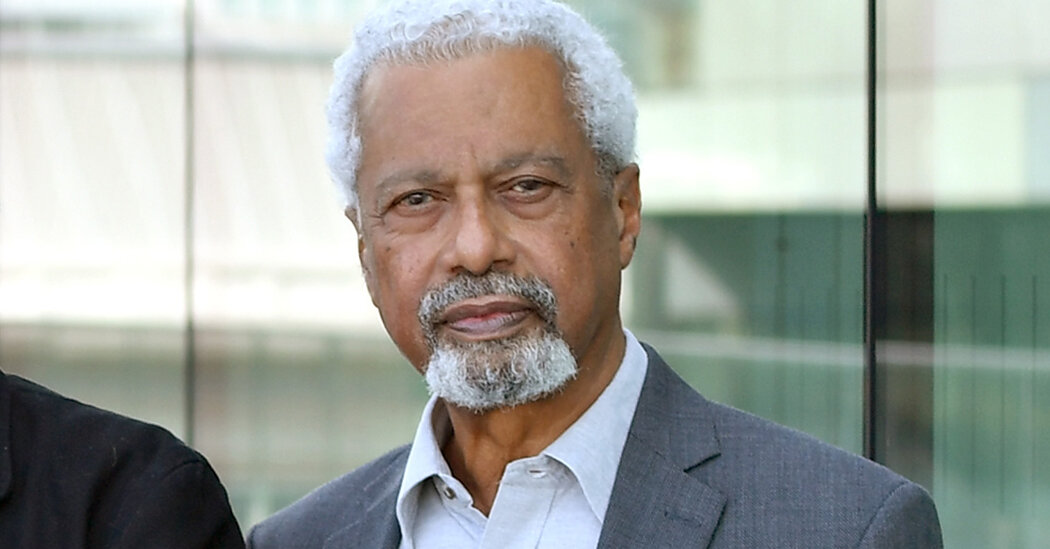

But despite being hailed as “one of Africa’s greatest living writers” by the author Giles Foden, Gurnah’s books have rarely received the kind of commercial reception that some previous laureates have.

Lola Shoneyin, the director of the Ake Arts and Book Festival in Nigeria, said that she expected the Nobel Prize would draw a larger audience for Gurnah on the African continent, where his work is not very widely known, and that she hoped his historical fiction might inspire younger generations to reflect more deeply on their countries’ pasts.

“If we are not looking very actively and deliberately at what has gone on in the past, how can we forge a successful future for ourselves in the continent?” she said.

Gurnah was born in Zanzibar, which is now part of Tanzania, in 1948. After moving to England, he started writing fiction in his 20s. He finished his first novel, “Memory of Departure,” about a young man who flees a failed uprising, at the same time he was writing his Ph.D. dissertation. He became a professor of English and postcolonial literatures at the University of Kent in Canterbury, teaching the work of writers such as Soyinka, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Salman Rushdie.

In both his scholarly work and his fiction, Gurnah has tried to uncover “the way in which colonialism transformed everything in the world, and people who are living through it are still processing that experience and some of its wounds,” he said.

The same themes that occupied him early in his career, when he was processing the effects of his own displacement, feel equally urgent today, he said, as both Europe and America have been gripped with a backlash against immigrants and refugees, and political instability and war have driven more people from their home countries. “It’s a kind of meanness and miserliness on the part of these prosperous countries that say, we don’t want these people,” he said. “They’re getting these literally handfuls of people compared to European migrations.