Jim Kaat’s father, John, raised him on tales of his baseball hero, Lefty Grove, who defined pitching dominance in the years before World War II. When Grove was inducted to the Hall of Fame, in 1947, John Kaat made the pilgrimage to Cooperstown, N.Y., to see him.

Jim Kaat would make many trips to Cooperstown, too, reveling in the chance to roam among legends. He played in the Hall of Fame Game in 1966, on the day Ted Williams and Casey Stengel gave their speeches, and returned through the years to honor teammates at their inductions — Harmon Killebrew, Mike Schmidt, Bruce Sutter and more.

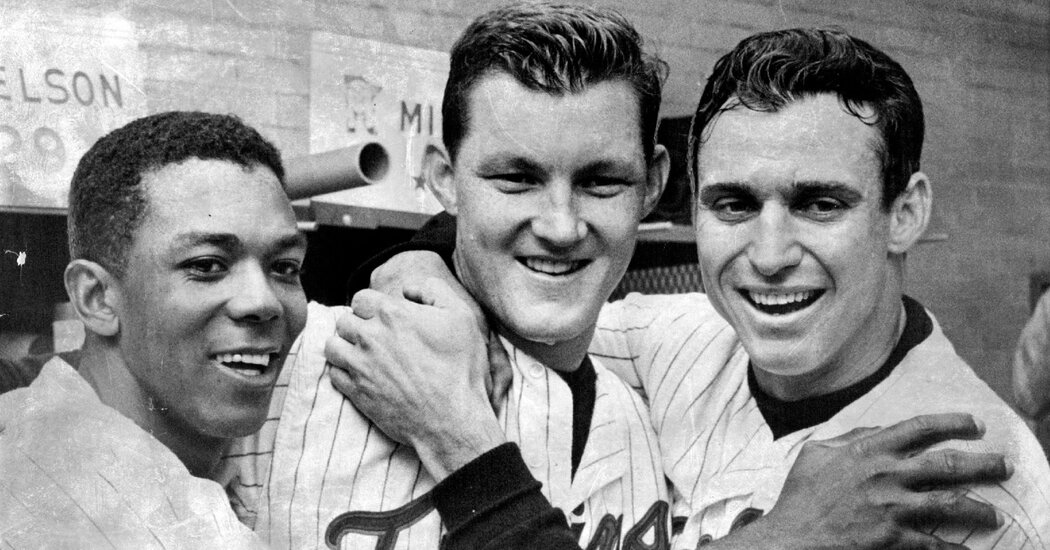

Now Kaat, at 83 years old, will have his own plaque in the gallery, as one of the six old-timers elected by a pair of committees that met on Sunday in Orlando, Fla. Kaat’s former Minnesota Twins teammate, Tony Oliva, also 83, was elected, too, along with Gil Hodges, Minnie Miñoso, Bud Fowler and Buck O’Neil.

All of the candidates had been considered and passed over before, including Hodges, Miñoso and O’Neil while they were still alive. The path to the Hall can be arduous for some, and Kaat sounded almost sheepish about his place in a room reserved for the giants of the sport.

“There’s got to be degrees of the Hall of Fame,” Kaat said. “I think they probably have a back row for me and I’ll wave to those guys up there. But it is pretty awesome to think of. I know when my career ended, Bowie Kuhn had told me it was the longest career for a pitcher in history.”

Kuhn, a former commissioner of Major League Baseball, was right: Kaat’s career spanned 25 seasons and was the longest ever at his retirement in 1983. Nolan Ryan now holds the record for pitching seasons, with 27, along with the records for strikeouts and no-hitters. Ryan is one of those no-doubt Hall of Famers, the ones who took the express lane to immortality with a first-ballot induction by the writers’ vote.

Dominance was not Kaat’s game. He had 180 complete games, won 16 Gold Gloves and went 283-237 with a 3.45 earned run average. But he is also the first Hall of Fame pitcher in the integration era (since 1947) to allow an average of more than a hit per inning (9.2 per nine). He spent most of his final five seasons as a situational reliever.

“I never really was a perennial No. 1 pitcher,” Kaat said, mentioning Grove, Warren Spahn, Greg Maddux and more. “All of those pitchers were No. 1 pitchers. I evolved, some years, into a No. 1 pitcher, but I wasn’t the guy that just said, ‘You’re going to start opening day for 10 years.’ I understood that and I know a lot of people in the past, the writers, said it took him too long to accomplish what he did.”

Candidates with splashier statistics — but far more complicated legacies — could join the 2022 class next month, when the Hall announces the results of the writers’ ballot, which includes David Ortiz and Alex Rodriguez for the first time, and Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens and Curt Schilling for the last. Players who are not elected by the writers can gain entry later through 16-person committees — or, as Bob Costas put it on MLB Network, “baseball’s court of appeals.”

The makeup of the jury, whose individual votes are kept secret, can heavily influence the outcome. Harold Baines, a longtime Chicago White Sox star, was elected in December 2018 by a committee that included Chicago’s team chairman, Jerry Reinsdorf, and its former manager, Tony La Russa. Former teammates like Schmidt, Rod Carew and Ozzie Smith — and contemporaries like Fergie Jenkins and Joe Torre — probably helped Kaat’s case.

“Whether it was exposure, being a broadcaster, that helped, I don’t know,” Kaat said. “I think what helped today was having players there I played with and against.”

Hodges, the slugging first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers who guided the Mets to a championship as manager in 1969, nearly made it on the writers’ ballot. Candidates need 75 percent of the vote to be elected, and Hodges got 50 percent in 1971, the year before his death of a heart attack at age 47. Until Sunday, Hodges (who peaked at 63.4 percent) was the only player ever to get 50 percent on the writers’ ballot without eventually making it in.

Miñoso, who died in 2015, never generated much attention from the writers but was finally recognized for a career that began in the Negro leagues and stretched to 1980, in a token appearance for his primary team, the White Sox. Miñoso, an outfielder, hit .299 with a stellar .848 on-base plus slugging percentage in nearly 2,000 games.

Oliva is a native of Cuba, like Miñoso, and won the American League batting title in 1964 and 1965, his first two full seasons. A left-handed hitting outfielder, Oliva made eight All-Star teams, won three batting titles overall and hit .304 with an .830 O.P.S.

“My family never had a chance to see me play in the United States,” Oliva said. “In Cuba I played very little, I only played every Sunday in the country. My mother, my father, my brother, they never saw me play. I wish they had the opportunity to be here today, but they’re in heaven right now, my father and my mother, they’d be very proud that their little country boy from Cuba is in the Hall of Fame today.”

Fowler and O’Neil were elected by a different committee than the others, one that considered players whose contributions predated the integration era.

Fowler, whose career began in the 1870s, was a pioneer in many regards who is considered by many to have been the first Black player to have played organized baseball against white players. O’Neil, a founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, was a star first baseman who spent decades around professional baseball as a manager and scout.

O’Neil died at age 94 in 2006, the year the Hall of Fame admitted 17 members from the Negro leagues, but not him. The Hall created a special achievement award in O’Neil’s name, but has at last given him the highest honor of all.