President Biden is unpopular everywhere. Economic concerns are mounting. Abortion rights are popular but social issues are more often secondary.

A new series of House polls by The New York Times and Siena College across four archetypal swing districts offers fresh evidence that Republicans are poised to retake Congress this fall as the party dominated among voters who care most about the economy.

Democrats continue to show resilience in places where abortion is still high on the minds of voters, and where popular incumbents are on the ballot. Indeed, the Democrats were still tied or ahead in all four districts — three of which were carried by Mr. Biden in 2020. But the party’s slim majority — control could flip if just five seats change hands — demands that it essentially run the table everywhere, at a moment when the economy has emerged as the driving issue in all but the country’s wealthier enclaves.

The poll results in the four districts — an upscale suburb in Kansas, the old industrial heartland of Pennsylvania, a fast-growing part of Las Vegas and a sprawling district along New Mexico’s southern border — offer deeper insights beyond the traditional Republican and Democratic divide in the race for Congress. They show how the midterm races are being shaped by larger and at times surprising forces that reflect the country’s ethnic, economic and educational realignment.

“The economy thing affects everyone while the social thing affects a minority,” said Victor Negron, a 30-year-old blackjack dealer who lives in Henderson, Nev., and who was planning to vote for the Republican vying to flip the seat from a Democratic incumbent. “If everyone’s doing good, then who cares what else everyone else is doing.”

In a polarized nation where more than 80 percent of House seats are entirely uncompetitive, the swing districts are, almost by definition, the competitive outliers. They are the rare places where Latino residents might vote Republican. Or blue-collar white voters are still winnable for Democrats. Or red-state suburbs could vote blue, or blue-state exurbs could go red.

In all four seats in Kansas, Pennsylvania, Nevada and New Mexico, the Democratic candidates were leading overwhelmingly among people who were more concerned with societal issues, garnering roughly 8 in 10 votes among voters who thought issues like abortion, guns and the state of democracy were most important to their vote. Similarly, the Republican candidates each won around 70 percent of the vote of those chiefly focused on the economy.

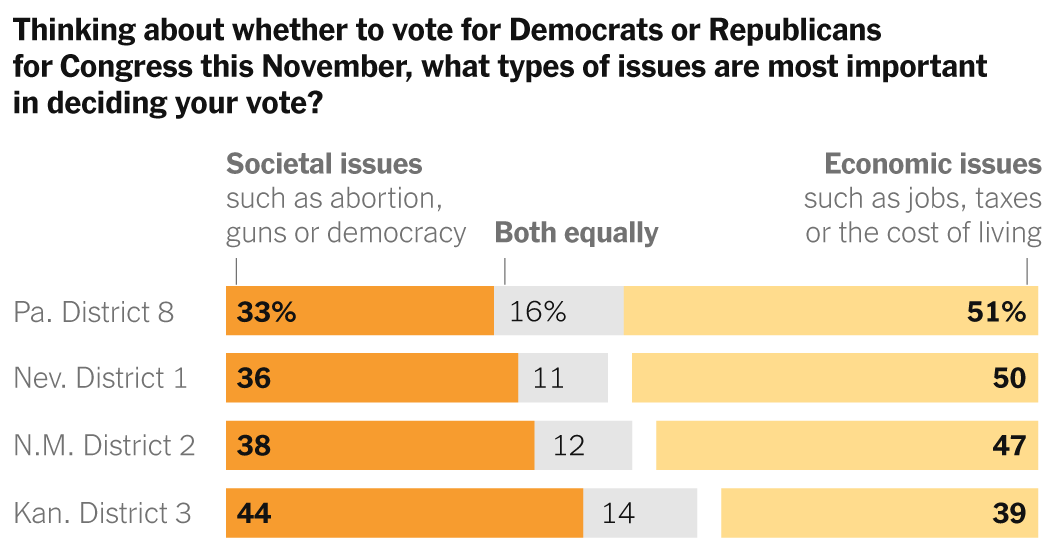

Which party was ahead on the ballot test was often a matter of what issues voters there prioritized.

In all four seats, most voters said they would prefer to vote for a candidate who thinks abortion should be mostly or always legal. But the issue’s power, relative to the economy, has appeared to fade in recent Times/Siena polling — except in the mostly highly educated and suburban battleground districts, and perhaps especially in the states where voters perceive abortion access at risk.

The challenge for Democrats is that resilience in well-educated suburbs or any other single kind of district will not be enough to hold the House. Weakness in just one kind of district, like rural Hispanic districts, could prove to be their undoing.

In 2020, Mr. Biden carried three of the four districts that were polled, yet today his approval rating does not top 44 percent in any of them, though the Democrats in all four seats were running ahead of the president’s poor ratings.

The State of the 2022 Midterm Elections

Election Day is Tuesday, Nov. 8.

Voters in three of the four districts were more focused on economics than social issues. The lone exception — Kansas’ Third District, a suburban area outside Kansas City that is one of the most highly educated in the country — is the only seat where a majority of voters hold a college degree, a group that is generally more insulated from economic hardship. Across all four districts, voters with a college degree were 11 to 15 percentage points more likely to prioritize social issues than those who did not graduate from college.

“Even if a candidate now is not promising me low taxes or financial incentive, the social issues right now are just too big,” said Deborah Hoffman, a 56-year-old Republican and database administrator who lives in Shawnee, Kan. This year, she’s planning to vote for the Democrat: Representative Sharice Davids, who was leading her Republican challenger, Amanda Adkins, in the survey, 55 to 41 percent.

Years ago, no political observer would have guessed that the suburbs of Kansas City would count as a bright spot for Democrats. The area had voted for every Republican presidential candidate dating back nearly a century, including Mitt Romney in 2012.

The Kansas district was at the epicenter of the fallout from the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade, as Kansas residents voted overwhelmingly to reject an initiative that would have ended abortion rights in the state. By a 61 to 25 percent margin, voters in the district say they would rather vote for a candidate who thinks abortion should be legal than illegal.

Over the last decade, American politics has realigned along educational lines, with highly educated areas lurching to the left and working-class districts trending to the right, opening the door for Republican breakthroughs in eastern Las Vegas, southern New Mexico and northeastern Pennsylvania. All of these areas backed Barack Obama in 2012 and countless Democrats before him.

In each of those three districts, around one-third of likely voters have a college degree. The economy was rated as the top issue.

Erika Horvath, 46, a single parent of two who has lived in downtown Las Vegas for five years, called this “the worst economy I’ve seen.” She said she was splitting her ticket this year but voting against Representative Dina Titus, the Democrat, and for her Republican challenger, Mark Robertson.

“It’s scary out here,” she added. “I haven’t seen this many looking for housing or jobs. Rents are way up.”

The survey showed that race tied at 47 percent — a stark turn for Ms. Titus, whose once solidly Democratic seat at the heart of Las Vegas has morphed into a battleground through a confluence of unfavorable demographic trends, a tough midterm environment and new district lines.

How Times reporters cover politics. We rely on our journalists to be independent observers. So while Times staff members may vote, they are not allowed to endorse or campaign for candidates or political causes. This includes participating in marches or rallies in support of a movement or giving money to, or raising money for, any political candidate or election cause.

Hispanic voters in Las Vegas’s eastside neighborhoods swung as much as 15 or 20 points toward Donald J. Trump in 2020. Mr. Biden still carried the boundaries of Ms. Titus’s new seat, which is Nevada’s most Hispanic, by 8 points that year.

But the survey showed Ms. Titus leading only narrowly among nonwhite voters in the diverse district, 51 percent to 40 percent, well beneath the margins that traditionally made Nevada’s First a Democratic-leaning district.

In New Mexico’s Second District, Representative Yvette Herrell, a Republican, is hoping that trend will help her hang on, too. Her district was redrawn to be more Democratic. Donald Trump carried the old district by 12 points, and under the new lines, Mr. Biden would have won the seat by 6 points.

Ms. Herrell has depicted her Democratic challenger, Gabriel Vasquez, as prioritizing environmental goals over the oil and gas jobs held by many Hispanics in the region. The poll showed a virtual tie, with Mr. Vasquez ahead 48 percent to 47 percent.

“I have four kids and I have a wife and a family that I take care of,” said Isaiah Hernandez, a 32-year-old cleaner who lives in Albuquerque. “It’s a lot different when you have to provide for a family than when you’re on your own.” He is planning to vote for Ms. Herrell.

Tony Sena, a 52-year-old plumber who lives in Albuquerque, is also planning to vote Republican next month. “If you don’t have a good economy, nothing else is going to matter as much,” he said.

The results in another district suggest that strong House candidates can still defy national trends.

Pennsylvania’s Eighth District has been at the epicenter of the realignment of traditionally Democratic, white working-class voters to the Trump-led Republican Party, and Mr. Trump carried the district by 3 percentage points in 2020.

The district, which includes the city of Scranton, prioritized the economy the most of all four districts polled, which should benefit Republicans. And Mr. Biden’s approval rating was the lowest here, too, despite his Scranton roots.

Yet Representative Matt Cartwright, a Democrat, leads his repeat Republican challenger, Jim Bognet, 50 percent to 44 percent.

Mr. Cartwright held 13 percent support among voters who said they backed Mr. Trump in the last presidential election, the most crossover support of any candidate in the polls. And he pulled off something else unusual: Across all four races, Mr. Cartwright was the Democrat who was winning the largest share of the vote both among voters focused on social issues and those focused on the economy.

After Mr. Cartwright, Ms. Herrell had the second most crossover support, drawing 11 percent of Biden voters despite voting against certifying the 2020 presidential election. She claimed that the 2018 race was stolen from her, too.

Ms. Herrell’s election denialism might seem like a deal-breaker in a district that voted for Mr. Biden. But issues related to democracy did not appear to be a strong motivator in any of the districts surveyed.

Around one-third of voters in every district said it didn’t matter whether a candidate thought Mr. Biden or Mr. Trump won in 2020, including around half of independents. Relatively few voters preferred a candidate that believed Mr. Trump won the election, though the 22 percent who said as much in Ms. Herrell’s district was the highest of any of the four polls.

And while New Mexico’s Second may have voted for Mr. Biden, it is also conservative and rural in parts — one where the right kind of Republican can make a pitch.

Ms. Herrell “understands the struggles and she also understands that we are wanting to keep the culture,” said Katana Wolf, a 39-year-old who works in behavioral health and lives in Las Cruces. “It’s a culture that’s just Las Cruces here.”

The increasing educational divide that the poll showed also was apparent in interviews.

Kelly Lieberman, a 58-year-old who lives in Overland Park, a leafy Kansas City suburb, is hoping Democrats prevail this fall, just as progressives did in her state’s abortion referendum. “We showed the country: We are not all crazies over here,” she said. “We can make rational scientific based choices.” She added, “Republicans are so unscientific.”

In Shavertown, Pa., Eugene Gingo, a 79-year-old Republican retiree, expressed resentment about those who went to college and who might look down on him.

“They think that they’ve got a degree and they’re experts,” Mr. Gingo said. “You get some of these Ivy League graduates that know nothing about the Civil War but yet they’re going to tell me. Again, it’s insulting.”

Ms. Lieberman is voting Democrat. Mr. Gingo is going Republican.

Reporting was contributed by Kimberley McGee in Las Vegas; Carey Gillam in Overland Park, Kan.; and Jon Hurdle in Scranton, Pa. Ruth Igielnik, Kristen Bayrakdarian and Sadiba Hasan also contributed reporting and analysis.