Companies selling private Medicare plans to older adults have posed as the Internal Revenue Service and other government agencies, misled customers about the size of their networks and preyed on vulnerable people with dementia and cognitive impairment, according to a new investigation of deceptive marketing practices in the industry released Thursday by the Senate Finance Committee.

Many individuals say they were enrolled in plans without realizing it.

The report, by the Democratic committee staff, catalogs complaints from 14 states, and a multitude of marketing materials generated by the insurers and the companies they hire to help sell the private plans.

The plans are part of a program called Medicare Advantage that now enrolls nearly half of all Medicare beneficiaries. The committee says people both in traditional Medicare and those already in a private plan have been inappropriately switched.

“It is unacceptable for this magnitude of fraudsters and scam artists to be running amok in Medicare, and I will be working closely with C.M.S. to ensure this dramatic increase in marketing complaints is addressed,” said Ron Wyden, a Democratic senator from Oregon and the committee’s chairman, referring to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the agency that oversees Medicare. “Medicare Advantage offers valuable plan options and extra benefits to many seniors but it is critical to stop any tactics or actors that harm seniors or undermine their confidence in the program.”

Medicare Advantage has become a highly lucrative market for health insurers. But many of the insurers selling such plans have been accused of overstating how sick their customers are, according to a New York Times review last month that found four of the five largest insurers have faced federal lawsuits accusing them of fraud.

“Because it’s such a profitable line of business, they have an incentive to do more marketing,” said Tricia Neuman, a senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation, who is working on a review of television advertisements by the plans. “And they have more money to do marketing, which increases revenue.”

Most of the behavior documented in the report came from insurance brokers or third-party marketing firms hired by the companies, not the insurers themselves.

The Senate report did not say which insurers benefited from the behaviors described. But it identified similar misleading behavior across multiple states, and an escalating number of complaints, suggesting that the tactics were not limited to a small group of bad actors.

Industry trade groups denounced the practices.

“America’s seniors and people with disabilities deserve Medicare Advantage (MA) plans that continue to deliver better services, better access to care, and better value,” Kristine Grow, a spokeswoman for AHIP, an industry trade group, said in a statement. “Health insurance providers are clear: Americans should be protected from bad actors who engage in misleading advertising and marketing tactics.”

She emphasized the federal government’s strict oversight of the industry’s marketing, including new rules that will require brokers to record their calls with potential customers and offer greater supervision of the third-party marketing groups enrolling new customers.

The Senate report pointed to several aggressive practices that it said amounted to fraud.

Five states said they were aware of brokers that had targeted people with cognitive impairment, and six states indicated people were signed up for a Medicare Advantage plan without even knowing it.

Marketing firms in several states sent mailers to Medicare beneficiaries made to look like correspondence from the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration or Medicare itself, the report said.

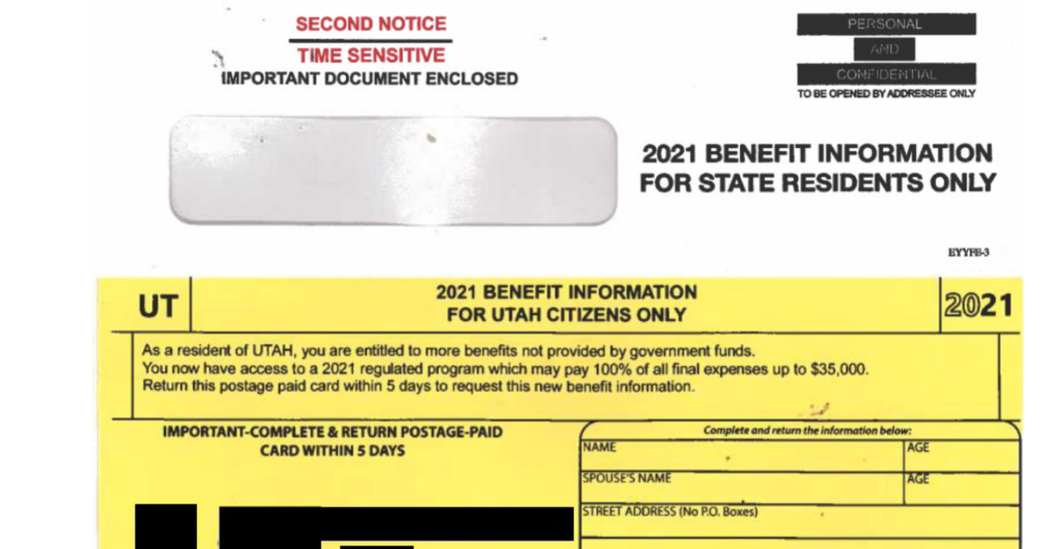

The mailings are designed to generate leads for insurance brokers. Federal rules prevent cold-calling of Medicare beneficiaries. But once respondents call, click or mail back a form, the companies are allowed to call them repeatedly. The investigation found similar forms from several states that looked like tax documents, using the font and layouts of an I.R.S. form. One Utah mailing declared: “IMPORTANT-COMPLETE & RETURN POSTAGE-PAID CARD WITHIN 5 DAYS.”

The report also said that a frequent refrain in television commercials and mailings was the idea that switching to Medicare Advantage would increase beneficiaries’ Social Security benefits. Some plans do charge lower premiums than traditional Medicare, but not most. Only 7 percent of beneficiaries this year were enrolled in a plan that offered such a premium discount, according to research from the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee.

The report described an Oregon man who enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan after hearing that switching would increase his Social Security check by $135 a month. It turned out that his new plan did not cover prescription drugs, and his Social Security income was unchanged because Medicaid already paid his Medicare premiums. “He was astonished and very stressed out when he went to the pharmacy,” according to a complaint cited in the Senate report. “He says he was never told that and would never have enrolled in a plan” without drug coverage.

Ten of the 14 states said people were confused about whether their doctors or the drugs they were being prescribed were covered under a plan. In Oregon, a patient was switched from traditional Medicare and a Medicare supplemental policy to a Medicare Advantage plan by an agent who came to her house. The new plan did not include her mental health provider as part of its network. Her claims, previously covered, were denied.

A 94-year-old woman with dementia in Missouri was sold a plan that did not include the hospital or doctors she saw in her rural area, according to another complaint. She was forced to travel significantly farther for her medical care.

Medicare Advantage plans have become increasingly popular. They are required to offer similar benefits to traditional Medicare, and many include extras like dental benefits, gym memberships or lower premiums. But the plans typically come with limited provider networks, which means that switching plans could mean losing access to doctors or coverage for certain prescriptions. Most Medicare beneficiaries are allowed to switch plans once a year, during a period known as open enrollment, which this year started Oct. 15 and ends Dec. 7.

That’s the time of year when the advertisements, mailers and telemarketers are most pervasive. Medicare has recently promised to increase its oversight this year and next, but the increasing popularity of the program and looser regulation under the Trump administration appear to have led to an increase in complaints to Medicare.

The report says that complaints to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services more than doubled, from 15,497 complaints in 2020 to 39,617 in 2021. Several state insurance regulators have also seen an increase.

“In some areas of the country, confused and embarrassed seniors have fallen victim to improper marketing practices,” said Ceci Connolly, the chief executive of the Alliance of Community Health Plans, who wrote last month to Senator Wyden about concerns that people were being misled into changing plans.

“It is very clear from the on-the-ground experience of our members that it has grown significantly,” she said in an interview. Plans say members are being switched to competing insurers without their knowledge, including one plan in which a beneficiary was disenrolled four times before ultimately being allowed to stay.

David Lipschutz, the associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy, which favors stronger regulation of the plans, said Medicare could be substantially more aggressive about enforcing the rules against deceptive marketing.

“Plans might try to distance themselves from this marketing misconduct and say we have no control over these agents and brokers or their brokerage firms, but C.M.S. has been pretty clear that plans are liable for the conduct of these downstream entities,” he said.

Medicare has told plans it will begin policing marketing materials more closely. Starting next open enrollment, Medicare will review and approve television advertisements before they air to make sure celebrities accurately describe the plans’ benefits. (One heavily shown ad that featured Joe Namath, the former star football quarterback, was changed to comply with regulations, according to the report.)

“C.M.S. remains committed to the shared goal of protecting people with Medicare from confusing and potentially misleading marketing while also ensuring they have the accurate and necessary information to make the coverage choices that best fit their needs,” said Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, the C.M.S. administrator, in a statement thanking the committee for the report.