Surveying the confusion unleashed by the airborne toxic event in “White Noise,” DeLillo writes, “In a crisis, the true facts are whatever other people say they are.” And as the Gladneys evacuate, passing the fully lit windows of a furniture store, then a motel, Jack is unnerved by all the unconcerned patrons, staring at them from inside. “It made us feel like fools, like tourists doing all the wrong things,” he says. “We were a parade of fools, open not only to the effects of chemical fallout but to the scornful judgment of other people.” Baumbach marveled at how accurately the book depicted what was happening now: the triple-guessing and self-consciousness, the ridiculous ways we are left to triangulate our fear in a catastrophe. And yet, he said, “the book wasn’t going through the pandemic. The book was written during sanity.” It had a clarity about this new reality, which he otherwise couldn’t apprehend.

He started in the middle of the book, just as an experiment — to see whether he could translate the most cinematic section, the evacuation sequence, into something scriptlike. Until then, the most actiony thing to happen in one of his films was arguably Ben Stiller running down a street in Brooklyn because he thinks someone has mistakenly left a restaurant with his father’s coat. To make “White Noise,” he would have to shoot a miles-long traffic jam, an attempted murder; a station wagon jumping through the air, Evel Knievel-style; and a mammoth C.G.I.-enhanced toxic cloud swallowing the sky. But Baumbach felt something as he worked on the adaptation in isolation that spring — momentum — and just kept going. His copy of “White Noise” was always there, after all, open on his desk, telling him what happened next.

The project was big and aspirational. It was also a life raft. Baumbach, Gerwig pointed out, was drawn to “White Noise” amid a “feeling of total uncertainty: Are movies going to get made again? Are people going to come? Are we just going to live off the fumes of the world that used to be? It allowed him, I think, to write something that, in other circumstances, would feel too big, too scary, too unwieldy, too much. It was almost like this dare: If they ever let us do it again, this is the one I want to do.”

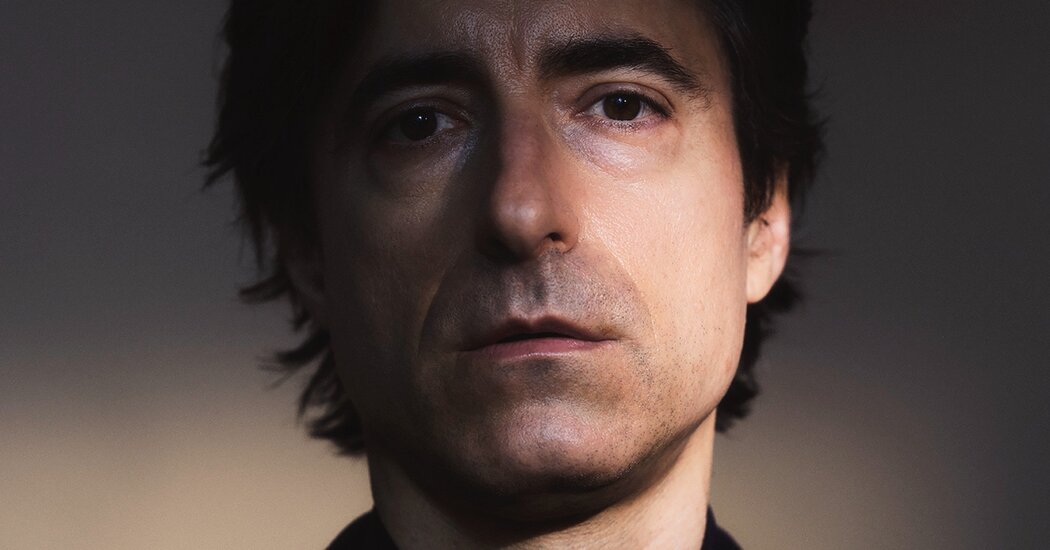

Baumbach is 53 and speaks in long, looping stops and starts and carefully considered multipoint turns, like a man trying to parallel park his consciousness into an impossible spot. We met for the first time in May in London, at a house in Notting Hill where Baumbach and Gerwig were staying while Gerwig shot her next film, “Barbie.” She and Baumbach wrote the script together, once he’d wrangled “White Noise” into shape. “We got into ‘Barbie’ mid-pandemic,” he said.

Baumbach was editing “White Noise” in a stand-alone building behind the house, set up with a workstation for his editor, Matthew Hannam, and a huge L-shaped couch facing a large screen. On the wall were three long rows of stills from “White Noise,” each about the size of a Polaroid, which they taped up, one by one, to track their progress. I spotted a close-up of Jack Gladney’s wife, Babette — an aloof-seeming but equally disquieted character whose own fear of death drives her to seek out a mysterious medication. Gerwig had pitched herself to Baumbach for the role after getting to a moment in the script when another character tells Jack that his wife has “important hair.” “I saw her incredibly clearly in my mind,” Gerwig said. “I saw her hair. I saw her glasses. I saw her acrylic nails.” Now, there she was on Baumbach’s wall, face suspended inside a permed, blond cumulonimbus: part lioness, part aerobics instructor.

Baumbach finished an initial cut of the movie about two weeks earlier. (The finished film comes out this month.) Now, while making a second, even more meticulous pass, he and Hannam were fixated on a long sequence that followed Jack, played by Adam Driver, around the Boy Scout camp to which people evacuated during the airborne toxic event. Driver, who has been in four of Baumbach’s previous films and has become a close friend, is 39 but appeared on the screen as a beleaguered man at least a decade deep into middle age. He’d raised his hairline with a wig, wore a chunky leather jacket and gained a proud, round paunch by drinking lots of beer. Driver, as Jack, walks through a crowded field of evacuees, buzzing with cross talk, when a colleague from the college appears: Murray Jay Siskind, played by Don Cheadle, a transplanted New Yorker and cultural-studies professor who doesn’t so much experience everyday life as improvise a scholarly monograph about it in real time. Flagged down by Jack, Murray exclaims, “All white people have a favorite Elvis song!” I laughed out loud. That’s what’s on his mind — how Murray chooses to greet his friend under the eccentrically apocalyptic circumstances.