After the coming apocalypse, when prizes are handed out for the best novels that presaged our end, Joy Williams’s new one, “Harrow,” will be a contender in the experimental category. Our mutant overlord critics will ask about it, squatting around a pixelated campfire, wearing goggles, sucking the marrow from squirrel bones, “What the hell was that?”

As Williams’s books go, this isn’t a very good one. Her wit misfires more than usual; the ecological themes are overly familiar; there are no real characters to hang onto, and very little plot, not that anyone comes to Williams for scenario.

Expectations are funny things, though. If you blacked out Williams’s name on the cover and told me that “Harrow” was written by a recent graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, I would probably have thought to myself, “A wild one has escaped the infirmary! I greet you, wild one, at the start of an interesting career. Please stop making me laugh while unspooling my intestines.”

Such are the mental contradictions when reading a lesser Williams novel.

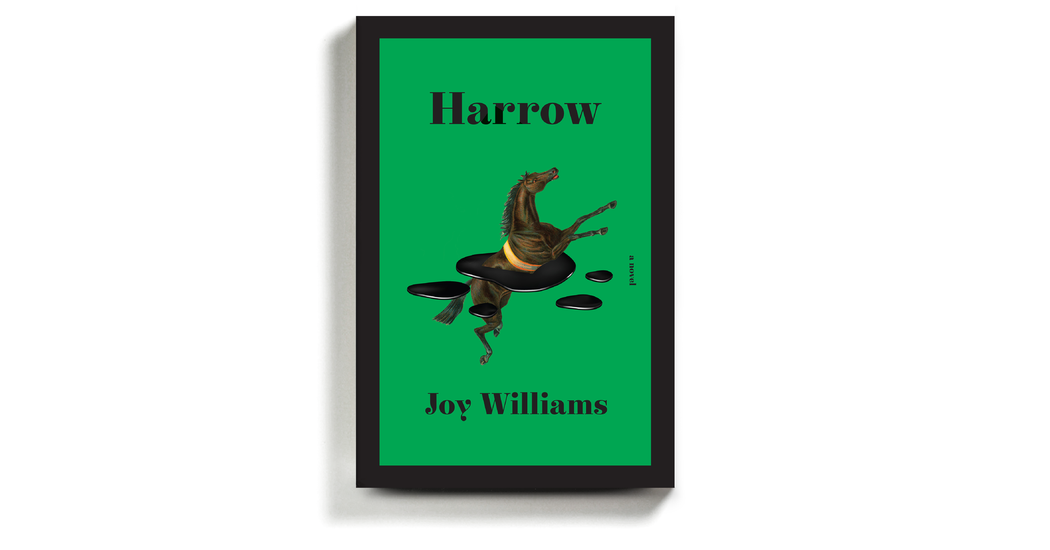

“Harrow” is her fifth novel. It’s about a teenager named Khristen who washes up, after some undefined natural cataclysm — there are no more birds or oranges, and cockroaches are kitten-size — at a faded retreat filled with elderly, vaguely fatuous eco-warriors.

It’s Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road” — a cynic, or a Williams character, might think — meets Mike White’s prickly, resort-themed “The White Lotus.” “We’ve been punched right back,” Williams writes, “to the Middle Ages.”

Khristen’s mom has told her all her life that’s she special, a chosen one of sorts, because she died briefly when young and then rose again. Khristen doesn’t feel special. No one but her mom thinks she is either, though she’s perfectly pleasant.

The best moments in “Harrow” arrive when we tag along with Khristen meeting the decrepit and exotic inmates — excuse me, the decrepit and exotic guests — at this old place. They’re a frisky if harmless sort of monkey-wrench gang, taking their last rolls with life’s fuzzy dice.

“They were a gabby seditious lot,” Williams writes, “in the worst of health but with kamikaze hearts, an army of the aged and ill, determined to refresh, through crackpot violence, a plundered earth.”

One man plans to blow himself up at a truck and bulldozer dealership. A woman is “supposed to shiv an herbicide representative but is dragging her heels.” A guy named Tom “had planned on going to a trophy-hunting convention and poisoning all there including the children with their tyke-sized AK-47s,” but he’s lost his eyesight.

They’re all too tired to think of grander missions, and they don’t really want to hurt anyone. No one’s contemplating, as Conrad suggested in “The Secret Agent,” blowing up the prime meridian, in the form of the Greenwich Observatory.

Khristen wants an assignment, too. “Maybe you should kill all the poets,” someone suggests, adding: “They’re so repulsively, tremulously anthropocentric.” The plan falls apart. Poets don’t gather often enough. And the angry ones are OK, right?

What’s left of America in this novel sounds as if it’s being run by a coalition of Trump dead-enders, shock jocks and every 1-800 accident lawyer from every unholy billboard. All conservation attempts are seen as reactionary. Tax breaks are given to households with guns, and thus “no one pays taxes because everyone has guns.”

Activists are imprisoned. “Nature had been deemed sociopathic, and if you found this position debatable you were deemed sociopathic as well.” The Smithsonian should get out and stick whatever nature is left into a breathable baggie, for permanent storage.

The wealthy raid blood banks, because transfusions are “tremendously rejuvenating and less superstitious than ingesting powdered rhino horn.”

Williams’s characters strike poses and dispense thought bubbles, verbal pellets; they can seem to have stepped out of a Jules Feiffer strip. Everyone skitters sideways, as if they were crabs. Her humans are given to epiphanic exclamations that often have nothing to do with anything that’s happening. They’re trying to remain sane in a demented world. They’re total weirdos, in the best sense.

Early in the novel, we meet a woman who’s described this way: “She was a sun-wrinkled dope-fogged ex-hippie whose highest ambition in life was to have someone give her an old Mercedes diesel that she could run on waste fry oil from the restaurant where she worked.” I read that sentence and laughed: There she is, an ur-Joy Williams character, double distilled.

You skim “Harrow,” as if it were a book of poems, for the author’s observations, threaded as they are with acuity and chagrin and strange harbingers and vestiges of old mythologies: “What came first in your opinion, Lola, the rabid rain or the birdless dawn?”; “Future humans, such a reckless concept”; “There aren’t meteors in meteor showers anymore. It’s just space junk from rockets and satellites”; “Have you ever seen anything stiller than a ham?”; “Something definitely had gone wrong. Even the dead were dismayed”; “That light show at the corner of your eyes is not a celebration in your honor, it’s the tumor moving in.”

My favorite detail in “Harrow” may be this one: There’s a television channel that broadcasts only minutes of silence. “They describe what the minute of silence is for and then they broadcast it. It’s all some people watch.”

In the novel “Winter” (2017), Ali Smith asked: “Things never go so wrong, do they, in real nature writers’ lives, that they can’t solve it or salve it by writing about nature?” Williams isn’t that kind of nature writer, one of the tenderheaded, cry-of-the-loon variety. Even if this novel is half-realized, like a wire frame awaiting clay for its head, its skepticism and sanity are consistently on display.

Someone wrote on Twitter recently that Williams’s fans should call themselves The Joy Division. That’s an agreeable idea for many reasons (I’d buy a hoodie), including how much crazy joy her characters derive from simply being outside and looking around.

As for those after-the-fall book prizes, whoever picks up Williams’s award can accept by reading this sentence aloud, from Page 123, as the entirety of the speech: “The world’s heartbreaking beauty will remain when there is no heart to break for it.”