Combine Walmart, Disney, Netflix, Nike, Exxon Mobil, Coca-Cola, Comcast, Morgan Stanley, McDonald’s, AT&T, Goldman Sachs, Boeing, IBM and Ford.

Apple is still worth more.

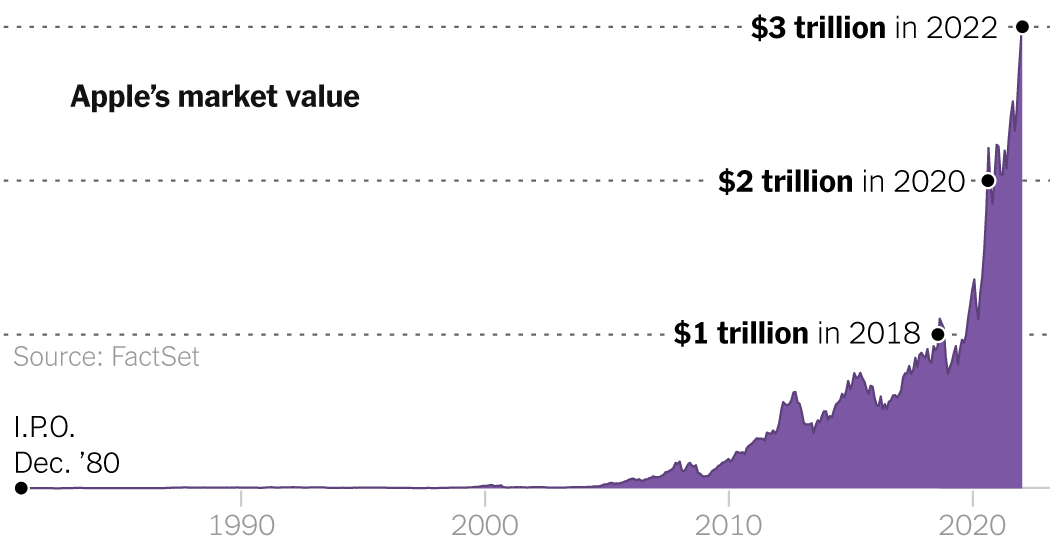

Apple, the computer company that started in a California garage in 1976, is now worth $3 trillion. It became the first publicly traded company to ever reach the figure on Monday, when its stock briefly eclipsed $182.86 a share before closing at $182.01.

Apple’s value is even more remarkable considering how rapid its recent ascent has been. In August 2018, Apple became the first American company ever to be worth $1 trillion, an achievement that took 42 years. It surged past $2 trillion two years later. Its next trillion took just 16 months and 15 days.

Such a valuation would have been unfathomable a few years ago. Now it seems like another milepost for a corporate titan that is still growing and appears to have few tall hurdles in its path. Another tech giant, Microsoft, could follow Apple into the $3 trillion club early this year.

“When we started, we thought it would be a successful company that would go forever. But you don’t really envision this,” said Steve Wozniak, the engineer who founded Apple with Steve Jobs in 1976. “At the time, the amount of memory that would hold one song cost $1 million.”

By just about any measure, a $3 trillion valuation is striking. It is worth more than the value of all of the world’s cryptocurrencies. It is roughly equal to the gross domestic product of Britain or India. And it is equivalent to about six JPMorgan Chases, the biggest American bank, or 30 General Electrics.

Apple now accounts for nearly 7 percent of the total value of the S&P 500, breaking IBM’s record of 6.4 percent in 1984, according to Howard Silverblatt, an analyst who tracks valuations at S&P Dow Jones Indices. Apple alone is about 3.3 percent of the value of all global stock markets, he said.

Behind Apple’s ascent is its tight grip on consumers, an economy that has especially favored its business and its stock, and its shrewd use of an enormous pile of cash.

When Apple unveiled the iPhone in January 2007, the company was worth $73.4 billion. Fifteen years later, the iPhone, already one of history’s best-selling products, continues to post impressive growth. In the year ending in September, iPhone sales were $192 billion, up almost 40 percent from the year prior.

The pandemic also sent sales of other Apple devices soaring, as people used them more to work, study and socialize, and sent investors fleeing to the safety of Apple’s stock in an increasingly uncertain global economy.

Apple’s immense sales and wide profit margins have provided it with a stockpile of cash big enough to buy a company like UPS, Starbucks or Morgan Stanley outright. At the end of September, Apple reported $190 billion in cash and investments.

“They’ve created the greatest cash machine in history,” said Aswath Damodaran, a New York University finance professor who has studied Apple.

Yet instead of making a major acquisition, or even trying something ambitious and expensive like building multiple factories in the United States, Apple has decided to largely give its cash back to its investors by buying its own stock.

Over the past decade, Apple has purchased $488 billion of its own shares, by far the most of any company, according to an analysis by Mr. Silverblatt. Much of that spending came after Apple used a 2017 tax law to move most of the $252 billion it had held abroad back to the United States. Apple is now responsible for 14 of the 15 largest stock buybacks in any single financial quarter, Mr. Silverblatt said. “They are the poster child,” he said.

An Apple spokesman said the company has spent more than $82 billion on research and development over the past five years, steadily increasing its investment each year, and that it employs about 154,000 people, or 38,000 more than five years ago.

Apple is also the largest taxpayer in the United States. In April, the company said it had paid $45 billion in taxes over the prior five years.

Economists are split over buybacks. Some economists say companies with excess cash should return the money to its shareholders. That it is far better for the economy than sitting on billions of dollars in cash, they say.

“This whole notion that buybacks are somehow going into a black hole is mystifying,” Mr. Damodaran said. “That is cash going to investors.”

Other economists say that buybacks are largely designed to increase a company’s valuation and that the money should instead be used to invest in the business, raise wages or even cut prices.

Apple, for instance, has spent billions of dollars buying its own stock while also using low-wage workers to assemble its products, working hard to avoid taxes and tariffs, and continually raising the prices on its devices.

“Apple could have gone and used that money to do all sorts of things. Instead, they’re using it to boost their stock price,” said William Lazonick, a professor emeritus of economics at the University of Massachusetts who has been a leading critic of buybacks since the 1980s.

Mr. Lazonick said that buybacks increase stock prices by encouraging investors to buy, and then causing momentum in the stock market as other investors look to cash in on the increase.

Stock buybacks reduce the number of total shares available for purchase. That makes each remaining share more valuable and improves the underlying fundamentals of the company in equations that large investors and automated trading systems use to pick stocks. As a result, the stock price climbs higher.

To Mr. Lazonick, a $3 trillion valuation is the result of a mix of factors. “It’s impossible to know how much of that is speculation, how much is manipulation and how much is innovation,” he said.

Kellen Browning contributed reporting.