On a brisk day back in February, the artist Adam Himebauch posted a screenshot of a Go Fund Me to his Instagram account: a successful campaign that appeared to have raised $255,336 of a $50,000 goal for a documentary recapping an illustrious career and life from the 1970s to the present. Seven months later, on social media, grainy stills and clips from the documentary announced his new installation at the New York City Museum of Contemporary Art’s satellite location.

The only hitch? There was no Go Fund Me; there is no N.Y.C. MOCA.

Throughout the past year, Himebauch, 38, a parodist as well as an artist, has been testing the boundaries of what even his inner circle thinks they know about him in “Back to the Future,” his project that includes digital performances and live exhibitions with in-person actors.

Using faux archival footage and social media — including an @nycmoca account and nearly two dozen fringe Instagram accounts (@adamhimebauchllc, which has more than 100,000 followers, and @adamhimebauchfanpage), Himebauch (pronounced hime-bock) has meticulously created the persona of an older, acclaimed artist in his late 60s to early 80s. By his own estimate he spends 30 to 50 hours per week painting at his TriBeCa studio — and some weeks, nearly as much time managing the 11-month-long digital project.

“Back to the Future” puts the art in artifice. The art is real — certainly, the brushstrokes on the canvases are his own. And his name, Adam Himebauch, isn’t a pseudonym. But the facts of his career are fuzzy, the timeline fabricated.

In the culmination of his scheme, Himebauch, who has been in New York City since 2011 and is originally from Delavan, Wis., has two exhibitions underway: a gallery show called “Retrospective,” at Trotter & Sholer gallery in Lower Manhattan; and the “N.Y.C. MOCA” installation, “Before & Back: Adam Himebauch,” at the Market Line, on the Lower East Side through the end of the year.

In “Retrospective,” he mimics an artist’s survey, showing the development of a talent from the 1970s on. Himebauch’s vivid landscape paintings in bold monochromes have titles like “Vincent Needle in Yellow Haze 1981” and “Deep Blue Japanese ZigZag 1979.” Stamped just beneath the name of each work is the year the painting actually was created — often, “2020.”

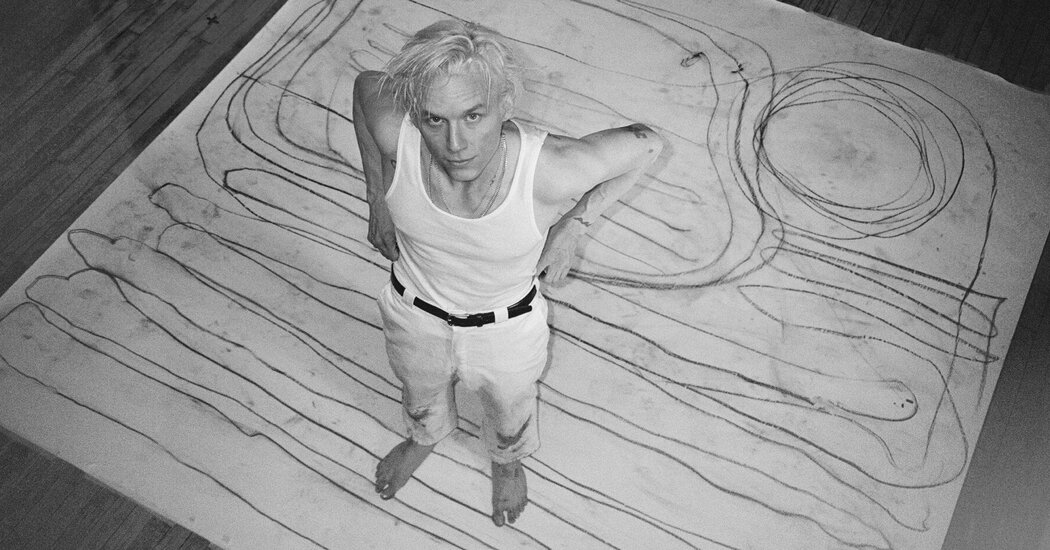

“Everything is done with a little bit of a wink, wink,” Himebauch, who defines himself as self-taught, said in a recent interview. He has been observed at the gallery sporting neck-length bleached hair that can make him look both 25 and 65, depending on the narrative he’s following (and the lighting).

Viewers typically learn about his exhibitions from his myriad social media accounts, which offer a slew of buzz-generating stunts: photoshopped bus advertisements, a “book release” with the German luxury art book publisher Taschen, “vintage” Himebauch “Jazz in the park 1982” T-shirts in soft pastels and “found” Super 8 footage.

Perhaps if all of this led to bad art, the project could be taken as pure cynicism. But that’s the thing — the art itself is pleasurable, with layers of colorful light that renders the landscape like vintage sepia photographs. Steeped in a longing for the natural world, Himebauch’s paintings are the reward for, if only momentarily, feeling like a fool. Suddenly, you’re part of the secret. The faux documentary, the photoshopped museum images and the book signing reveal a laboring artist with the amiable courtesy you’d expect of a transplant from Wisconsin. It’s all more silly than sardonic.

“What made it worth doing the show is that the work is really good,” said Jenna Ferrey, the owner of Trotter & Sholer. “It can stand on its own.”

The Fine Arts & Exhibits Special Section

The paintings, all for sale, range from $5,000 to $9,500.

“There’s a bit of tongue-in-cheek commentary on perceived value and the kind of endorsements that art receives,” she said.

The artist gives a peek behind the curtain in a flier at the entrance to the gallery, revealing that his project “constructs a reality” of past and future.

“Truth, in the context of this project, is a currency,” it reads.

Ferrey said that by the time a buyer reaches the point of purchase, they tend to know what’s going on. If not, she clues them in. “It’s a fun mind game that you get to play with us, not that you’re being tricked,” she said. But not everyone is convinced.

“Art is not supposed to be tongue in cheek, not if it’s good,” said Robert Dimin, 42, the partner and sales director of Denny Dimin Gallery in Lower Manhattan, who calls the “Back to the Future” project “marketing hoopla.”

Dimin said that had the pieces been priced according to what an artist of Himebauch’s reputed stature would generate — six to seven figures per painting — he might feel the project had tipped into legitimacy beyond an act of public relations.

For an institutional critique to work “it has to go as deep as it possibly can go,” he said.

Of course, adding zeros to the prices would risk them not selling at all. Three of the six works on display have been sold, Ferrey said.

A boxy, old-style television in Trotter & Sholer’s window flashes images of Himebauch as a baby intermixed with footage from the documentary: Himebauch running on a rooftop, on the cover of Life magazine, drawing with his body on a canvas on the floor à la Jackson Pollock; Himebauch in black and white with a rope tied around his waist, harking back to the “Art/Life One Year Performance” of Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano from 1983-1984, when the two artists were tied together for an entire year with an 8-foot rope around their waists.

After the double-take, the performance starts to feel like a quiz: Can you name each of the canonical art history references?

“It’s extremely unoriginal,” said Will Corwin, a sculptor and New York art critic. “It seems to be more about an expensively produced, pretty poorly conceived and gimmicky ironic takedown of the art world, spoofing Andy Warhol primarily, and also playing with what we think of as vintage retro European and ’70s TV art coverage. It’s not really convincing.”

Convincing or not, Himebauch joins a storied list of alter ego tricksters. Elements of his performance recall the comic Andy Kaufman, who left behind an incendiary lounge singer persona Tony Clifton; Colin de Land and Richard Prince, who are thought to be the artists behind the fictive painter John Dogg (Prince once opened a fake art gallery, also in the Lower East Side); and Jayson Musson, who through online videos created the hip-hop alias Hennessy Youngman and rose to fame with his biting criticism of a predominantly white art world.

Social media hypes are having a moment. Last month, the marketing for the collaborative album by Drake and 21 Savage, “Her Loss,” included a concoction of fake Vogue magazine issues and fabricated appearances on NPR’s Tiny Desk series and “The Howard Stern Show,” which The New York Times pop music critic Jon Caramanica called “chum” for fans. And earlier this year, Harry Styles fans were left perplexed after it was revealed that a YouTuber named George Mason had started a “secret” TikTok account as the star.

Himebauch himself is no stranger to stunts. He was previously known for his satirical street graffiti under the artist name Hanksy, in which he reproduced Banksy images with Tom Hanks’s face appended. At Hanksy’s peak, he became known for a 2015 mural in Manhattan’s Chinatown of Donald Trump’s face layered atop a pile of feces surrounded by buzzing flies, an image that spawned replica posters all over downtown.

Now, he is back to keeping his fans guessing, and the art crowd on its toes.

On the opening night of “Before and Back” in September, at “N.Y.C. MOCA,” at the Essex Market, a man who resembled an older Himebauch caused stares and confusion: Clad in a black beret and World War II bomber jacket, Peter Millard, 77, a Manhattan-based designer, casually strolled around as Himebauch at the artist’s request.

“I walked in as him,” Millard said.

Some art gazers approached him with reverence. “They would ask, ‘Oh are you Adam?’ And I would say, ‘Yes, I’m Adam now,’” he said.

At one point Millard was offered a bouquet of flowers. The real Himebauch, unhidden, stood a mere few feet away.

In addition to drafting his elder doppelgänger, Himebauch also hired actors to play the assistant curator and exhibition guide who handed out brightly colored clip-on buttons with the words “N.Y.C. MOCA,” a nod to the old Metropolitan Museum of Art metal tags given to visitors from 1971 to 2013.

The fictional museum’s “satellite exhibition” even caught the attention of the official Instagram account for New York State tourism, @iloveNY, which on World Art Day reposted Himebauch’s fake 2014 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in which he superimposed images of his own paintings onto real photos of the museum’s gallery halls.

(Hypebeast, a culture and lifestyle site, published an article promoting Himebauch’s fake documentary and upcoming coffee table book. Was the coverage part of the act? The answer is predictably cloudy. Himebauch, who is friends with the editor, says that the story wasn’t choreographed.)

At the opening of “Retrospective” last month, Dimes Square creatives dressed in red leather and billowing trousers spilled out of the 500-square-foot gallery and onto the street; a pianist played on the sidewalk; small batch French wine was passed in plastic cups. Onlookers couldn’t help but poke in their heads.

One passer-by entered the gallery and inquired who the artist was. When Himebauch’s publicist, Sydney Schiff, pointed to the youthful artist, the man look surprised.

“How were you painting in the 70s?” he asked him.

Himebauch replied with a smile, “A really good skin care routine.”

Retrospective

Through Dec. 17 at Trotter & Sholer, 168 Suffolk Street, Lower Manhattan; trotterandsholer.com.

Before & Back: Adam Himebauch

Through Dec. 31 at the Market Line, 115 Delancey Street, Manhattan (lower level of Essex Crossing beneath the Essex Market); marketline.nyc.