Joe Biden is selling. But is anyone buying?

The president, a used-car salesman’s son who sees himself as a consummate political pitchman, is stepping up efforts to promote his hard-won, $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure package to the public, in hopes of branding it is as his apex achievement, reversing his recent plunge in the polls and boosting Democrats’ chances in the 2022 midterm elections.

Among Democrats, however, concerns are growing about whether the White House — hurtling from crisis to crisis — can mount the sustained campaign necessary to reframe a sprawling bill that was gridlocked for months into a triumph that will help them hold Congress.

The package is already popular, with a solid majority of voters saying they support its funding increases for rail, roads, ports, water systems, broadband and the power grid. But the president and his allies are under no illusion about what they are really selling — Mr. Biden himself, and his theory-of-the-case for American politics, that delivering on concrete campaign promises is the only way to transcend the rage and culture-war messaging of Trump-era politics.

“When you do fundamentally helpful things for people, and you make sure they know about it, you will get credit for it,” said Jared Bernstein, a longtime economic adviser to the president, summing up the Biden brand, and the plan for his comeback in the polls.

Yet the challenges facing Mr. Biden — who, as President Barack Obama’s vice president a decade ago, had some success serving as a traveling salesman for the stimulus and health care bills — are formidable.

The infrastructure bill is intended as a long-term solution to decades of neglect. Many of the projects will not be selected, much less completed, for years — so many Americans might not immediately see the windfall. And Mr. Biden, for all of his Amtrak gusto, is not an especially consistent messenger.

Moreover, the initial enthusiasm about the bill has been sapped by months of intraparty squabbling that trapped the president “in the sausage-making factory,” as a senior White House aide put it. And a new fight over the unresolved $1.85 trillion social spending plan threatens to send him right back into the legislative grinder. Rising inflation and pessimism about the economy, coupled with the lingering pandemic, and the hangover from the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan, have soured the public mood and pushed Mr. Biden’s once-robust approval rating to the low 40s.

While 32 Republicans — including Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the minority leader, voted for the package (he called it a “godsend” for his state this week) — the party is already trying to dilute its political impact. Some Senate conservatives have even cast its passage as a victory of sorts for former President Donald J. Trump, whose halfhearted push on infrastructure became a running joke.

On Tuesday, Representative Sean Patrick Maloney of New York, who heads the campaign committee for House Democrats, warned the White House not to squander the moment, telling The New York Times that Mr. Biden “needs to get himself out there all around the country” before “the next crisis takes over the news cycle.”

He concluded with a message to White House staff: “Free Joe Biden.”

One of the president’s closest allies, Representative James E. Clyburn, Democrat of South Carolina, sees it as a race against time to brand the victory as a Biden accomplishment. His biggest worry, he said in an interview, was that Republicans would simply start showing up at ribbon cuttings to celebrate projects many in their party opposed.

Mr. Clyburn pointed to one example he encountered back in his home state this week: Gov. Henry McMaster, a Trump-allied Republican, appeared at a groundbreaking for a popular $1.7 billion highway project that was funded, in part, by a state tax increase he had initially vetoed.

“Democrats have never done a good job of telling people what we have done,” said Mr. Clyburn, the third-ranking Democrat in the House. “We’ve got to do the work, sure, but then we’ve got to go back and tell people that we’ve done it. We got to get off our duffs.”

White House officials are also eager to make a quick sale on infrastructure. The Build Back Better Act, which includes a dizzying array of social spending programs, is also popular but is likely to face unanimous opposition from Republicans. Recent focus groups conducted by Democratic pollsters indicate that swing voters might be swayed against the new package by messaging that depicts it as “socialist” overreach.

Mr. Biden’s team argues that both bills are a political boon, and say they are intent on taking full advantage of his infrastructure win as quickly as possible. The president has participated in strategy meetings, impatiently instructing aides to simplify their descriptions of programs so voters can more easily understand them, according to a Democratic official who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss internal deliberations.

Mr. Biden scheduled a White House signing ceremony on Monday that will include legislators, mayors and governors from both parties, followed by trips around the country over the next week to sell the plan.

In addition, the administration is turning back to an infrastructure sales force of sorts in dispatching cabinet members, led by Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg and Energy Secretary Jennifer M. Granholm, to promote infrastructure investments in cities, towns, rural areas and tribal communities. Vice President Kamala Harris will also play a role, according to Andrew Bates, a White House spokesman.

The administration is also preparing a messaging blitz on television and media outlets targeted at Black and Hispanic communities, the Democratic official said. The White House digital team is developing social media explainers and videos to promote the benefits of the infrastructure plan to different constituencies.

“You can have surrogates both span out across the country and talk about your policies, but at the end of the day, it’s the president’s agenda, it’s his vision, and he’s got to be the one selling it,” said Mike Schmuhl, who managed Mr. Buttigieg’s 2020 presidential campaign and now serves as the chairman of the Indiana Democratic Party.

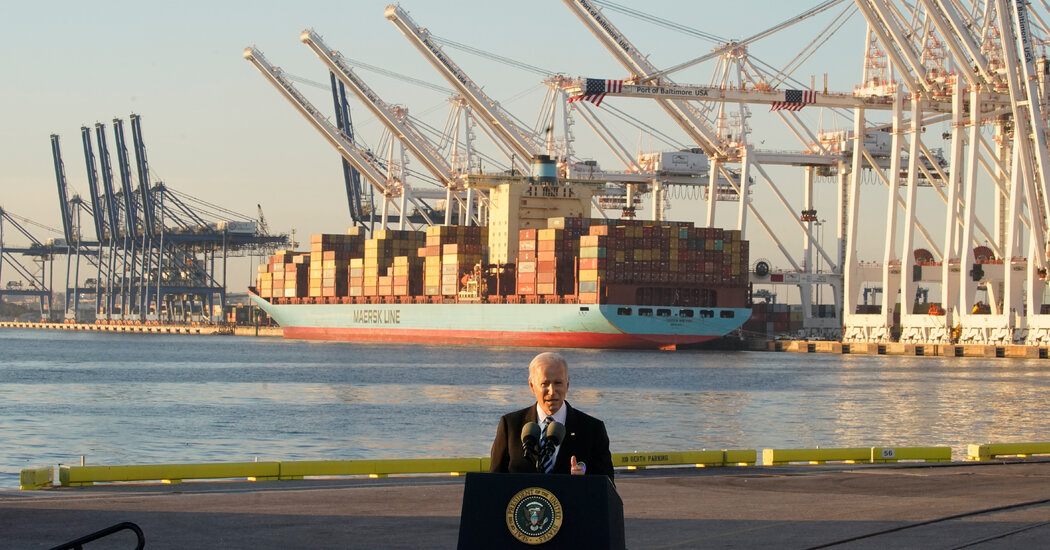

But Mr. Biden does not have the luxury of focusing exclusively on selling the bill. His appearance on Wednesday at the port of Baltimore, for example, was not strictly an infrastructure event: It was intended to address growing concerns about the supply chain bottlenecks, in addition to publicizing the $17 billion allocated in the bill for improvement at ports.

The Infrastructure Bill at a Glance

In many ways, Mr. Biden’s current challenge echoes the task he confronted in 2010 and 2011 when he was dispatched to states and cities to sell Mr. Obama’s stimulus and health care plans, which were unpopular at the time, and passed with virtually no Republican support.

Aides to both Mr. Obama and Mr. Biden said he was, in general, an enthusiastic and effective salesman, especially adept at glad-handing with local officials and hugging it out with regular citizens, skills that later helped him reassure voters he was the best pick to replace Mr. Trump.

But Mr. Biden, then as now, had a tendency to ramble on and commit his share of gaffes. (One former West Wing aide recalled watching the daily clips of his appearances with clenched fists.)

At the time, Mr. Biden pressured Mr. Obama, with little success, to spend less time in Washington focusing on governmental process, and more time on the road explaining his policies to voters — the same request Democrats are now making of Mr. Biden.

“We have a great opportunity to go out and sell a bill that genuinely has an impact on people’s real lives,” said Representative Josh Gottheimer, a New Jersey Democrat who is likely to face a serious challenge next year in a suburban New York City swing district. “But everyone has to really go out and make the case for it — and celebrate it — if it is going to be helpful for Democrats in seats like mine in 2022.”

But Mr. Biden’s centrist strategy, rooted in his desire to revive a bygone era of bipartisanship, is also providing a safe haven for a handful of moderate Republicans who are betting that delivering results for their constituents will offset the damage of a fleeting alliance with a Democratic president.

“It is a difficult time to act in a bipartisan way, and some of the phone calls I’ve gotten to my office are a reflection of that,” said Nicole Malliotakis of New York, whose district includes Staten Island and southern Brooklyn. She was one of 13 House Republicans to vote for the package.

“Sadly, you have a lot of people who are more concerned with the optics of giving the president some credit,” she added. “But it’s my job to serve the people who elected me, and they want me to deliver real infrastructure because we’ve got real problems here — we’ve got constant flooding, and we have got to deal with our inadequate sewer systems.”