Legislatures in 16 states, Florida outstanding amongst them, have been deliberating rolling again little one labor legal guidelines. In some instances, main steps have already been taken to loosen restrictions on work by youngsters as younger as 14. The erasures, virtually solely promoted by Republicans, goal authorized prohibitions towards little one exploitation which have been in place for almost a century.

Right here’s a shock: Radical transformations in pictures are one major cause the threatened rollbacks have gotten traction.

Within the first decade of the twentieth century, sociologist Lewis W. Hine (1874-1940) picked up a digicam and skilled it on a budget labor carried out by kids, which had turn into commonplace all over the place from Pittsburgh metal mills to Carolina textile factories, from an Alabama canning firm for shucked oysters to West Virginia factories for glass. When revealed, Hine’s haunting photos scandalized America, and legal guidelines to guard youngsters emerged.

A whole fashionable creative style — documentary pictures — was weaned on the rising social effort to rein within the abusive observe of forcing kids to toil in sweatshops and on farms within the wake of the Gilded Age. Emblematic is Hine’s luminous image of a younger lady — known as a spinner — at North Carolina’s Whitnel Cotton Mfg. Co. He positioned the shabbily dressed little one between a seemingly never-ending row of whirling textile bobbins, the place her job was to patrol the interminable line and speedily restore damaged threads, and a row of manufacturing unit home windows the place gentle streams in from open air to light up the inside scene. She has stopped her work to face the digicam, clearly on the photographer’s instruction.

Lewis W. Hine, “Cotton Mill Worker, North Carolina,” 1908; gelatin silver print.

(J. Paul Getty Museum)

Her proper hand, fingers curled, rests on the infernal machine, whereas her left hand is open on the windowsill. She’s a juvenile hostage, an harmless trapped between captivity and freedom.

A spinner’s toil in a textile mill was not particularly harmful, though lack of a finger was actually a danger. Nonetheless, as Stanford artwork historian Alexander Nemerov has sharply noticed, the harm recorded in Hine’s entrancing {photograph} was inflicted at the very least as a lot on the younger lady’s soul as on her physique. An aura of entrapment is evoked. A repetitive, tedious, mechanically decided routine is her current and her future, stretching into infinity. When her targeted gaze meets yours, a coiled look of resignation stiffens her mushy face, and it’s painful to see.

You may transfer on. However for her, that is it.

The transformation in pictures immediately just isn’t that artists have deserted a productive curiosity within the state of the world, together with these types of merciless labor situations, which social documentary pictures discover. They haven’t. LaToya Ruby Frazier is one spectacular instance.

“The Last Cruze,” her transferring exhibition at Exposition Park’s California African American Museum in 2021, registered the lives of union staff on the Basic Motors plant in Lordstown, Ohio — staff displaced and disrupted when the manufacturing unit was shuttered two years earlier. Frazier’s set up of 67 black-and-white pictures and one shade video informed an unflattering story of the human aftermath, and it did so in fascinating methods.

However additionally it is truthful to say that her soulful set up didn’t — couldn’t — generate the identical form of outrage that Hine’s pictures did. In 1908, when he started to publish his pictures of younger kids working underneath bleak situations in factories and on farms, the context during which the images appeared was radically completely different from immediately’s visible surroundings.

Lewis W. Hine, “Oyster shuckers, Biloxi, Miss.,” circa 1911; gelatin silver print.

(J. Paul Getty Museum)

As we speak, residing in a media-saturated panorama, there’s no escape from them. Solely hardly ever do they disrupt. Get up within the morning, verify your telephone, and scores — perhaps even a whole bunch — of images flash by earlier than breakfast. In such a milieu, Hine’s troubling 1908 pictures would simply disappear, maybe seizing a second however quickly evaporating into the visible miasma that floods the zone each day.

And now, with the arrival of synthetic intelligence, assumption of a direct connection to actuality unravels. Skepticism about photographic authenticity arises.

Hine, then in his early 30s, was a part of a rising Progressive motion that sought large-scale social and political reform following the collapse of post-Civil Warfare Reconstruction and the explosion of the greedy Gilded Age. John Spargo, a self-educated British stonemason who emigrated to New York in 1901, turned an unlikely political theorist of the motion. His guide “The Bitter Cry of the Children” fiercely condemned little one labor practices, arguing partly that interrupting college with work prompted lifelong impairment.

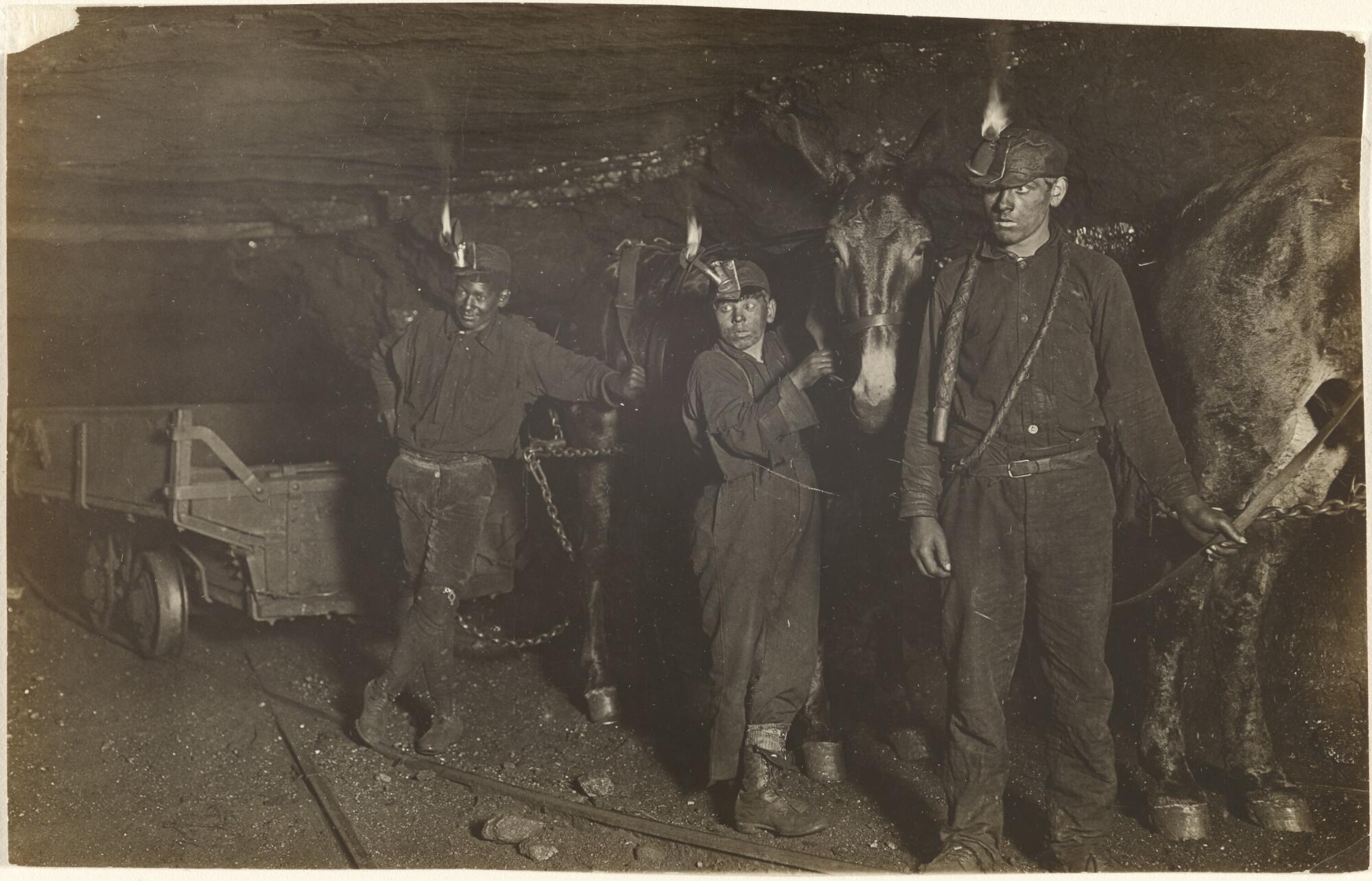

“Three young coal miners, with mules; Pennsylvania,” 1908; gelatin silver print.

(J. Paul Getty Museum)

Novelists as completely different as Jack London and H.G. Wells agreed, they usually stated so briefly tales and journal essays. A non-public, nonprofit Nationwide Baby Labor Committee shaped to foyer state and federal officers, whereas embarking on public training. The NCLC employed Hine.

His analysis expertise as a sociologist had led him to the pioneering pictures of Jacob Riis, a police reporter for the New York Tribune. Riis uncovered Decrease East Facet slum situations in tenement pictures that may kind the idea for his famend guide, “How the Other Half Lives.” Hine, recognizing the ability of pictures as visible proof, quickly picked up the digicam too.

His pictorial paperwork of kid labor started to appear in weekly magazines, like Charities and the Commons, and in broadly distributed NCLC pamphlets with such dry if explanatory titles as “Child Labor in Virginia” and “Farmwork and Schools in Kentucky.” The publications may need had restricted circulation, however their poignant pictures seeped into the favored press.

For readers who didn’t spend their days strolling the manufacturing unit flooring or supervising the sorting of coal chunks sliding down a chute, an incisive image would stand out. Witnessing {a photograph} of a naive little one climbing up barefoot into large equipment or shadowed beneath huge tobacco leaves sprayed with pesticides may simply stick within the thoughts.

Lewis W. Hine, “10 year old picker, Gildersleeve tobacco farm,” 1917; gelatin silver print.

(J. Paul Getty Museum)

Hine’s 1917 image of a 10-year-old boy working Connecticut’s Gildersleeve tobacco farm, south of Hartford, reveals him on his knees in an irrigation ditch between rows of what’s most likely the powerful tobacco used for cigar wrappers. (Extra tender tobacco, shredded for the filling, was grown within the South, not New England.) It’s the primary selecting, when three absolutely grown leaves close to the underside of the stalk are lower and stacked. First one aspect’s plant, then the opposite’s, could be picked — and on the kid would go, plant by plant within the humid, late-summer warmth down prolonged rows overlaying acres of farmland.

Quickly, the second tier of leaves would mature and the method repeated. Then the third tier was prepared, picked whereas reaching up, and so forth till, standing, the plant was absolutely harvested.

The labor’s grueling tedium is stifling. My very own first summer season job as a child in quest of after-school pocket cash was selecting cigar tobacco on a Connecticut farm simply north of Hartford. I used to be 14. I lasted lower than per week. Hine’s tousled little boy, who seems forlornly into the digicam with scowling darkish eyes beneath a furrowed forehead, probably had no such liberating selection.

As we speak’s drive to roll again state little one labor legal guidelines is being pushed by conservative teams just like the Basis for Authorities Accountability in Naples, Fla., a well-funded anti-welfare group. (Mockingly, in accordance with its 2023 tax submitting, the CEO of the FGA, a nonprofit looking for to loosen little one labor restrictions, obtained greater than $498,000 in wage and different compensation.) In that tourism-dependent state, the Orlando Weekly reported that Gov. Ron DeSantis’ workplace wrote his state’s invoice, saying adjustments made by the legislature final 12 months to loosen working restrictions for minors “did not go far enough.” If handed, youngsters as younger as 14 may work in a single day hours on college nights or lengthy shifts and not using a meal break.

The Miami Herald reported that, in protection of his plan, the governor defined to the Trump administration’s border czar {that a} youthful workforce might be a part of the answer to changing “dirt cheap” labor from migrants within the nation illegally. The invoice, he added, would “allow families to decide what is in the best interest of their child.”

Lewis W. Hine, “Cranberry picker, New Jersey,” 1913; gelatin silver print.

(J. Paul Getty Museum)

DeSantis requested, “Why do we say we need to import foreigners, even import them illegally, when you know, teenagers used to work at these resorts; college students should be able to do this stuff.”

Faculty college students, in fact, are adults, not kids, their common age between 18 and 25. And the Baby Welfare League of America notes that, in 2022, dad and mom dedicated 71% of reported little one abuse in Florida, so an enchantment to household decision-making as a alternative for legal guidelines regulating little one labor is fraught.

The historic instance of Lewis Hine’s distinctive documentary pictures — and their useful impression on kids’s lives — would assist illuminate the present, extremely contentious topic. His work is discovered in lots of public collections. The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y., are two that maintain 1000’s of prints and negatives. The Getty Museum in L.A. has greater than 100.

However there’s a hitch: Nonetheless a lot artwork museums immediately categorical a dedication to social relevance, their programming is the alternative of nimble. It takes years to provide and schedule an exhibition. As we speak’s little one labor battle may be over.

If ever there have been an important cause for a digital present on an artwork museum’s web site to be offered and vigorously promoted, that is it. Through the first Trump administration, the favored digital journal Bored Panda did simply that, mounting an in depth anthology of Hine’s riveting little one labor pictures. Demand for affordable labor by no means goes away, however typically it crests. We’re there once more.

Lewis W. Hine, “Newsboy, Mobile, Alabama,” 1914; gelatin silver print.

(J. Paul Getty Museum)