Everything has been fried up as if in a goblin’s skillet. The result is wicked, in every sense of that word. The kids take some goofy, quasi-Luciferian pride in it all.

One day, the landlord and a property developer turn up. “No matter who you are,” Darnielle writes, “you always notice how the adults wreck everything as soon as they show up on the scene.”

The two are dispatched, gruesomely, with an enormous sword. Incredibly, no killer is caught. This is pre-internet, and the murders take on the quality of myth. There are rumors of “dead bodies atop a pyre of pornography, cryptograms in graffiti, the specter of teenage satanic rites.”

Chandler begins his reporting two decades or so after the murders, hoping to wrestle some clarity from “the muddy beginnings in which legends are conceived.” He’s methodical, obsessive. He pores over eBay listings, which have become a happy hunting ground for crime fetishists.

Chandler recounts these kids’ stories. He reconnects with a childhood friend. There are many subtle flicks in perspective.

Chandler reconsiders, at length, one of his early books, “The White Witch of Morro Bay,” about a young schoolteacher who murdered two students who broke into her apartment, stabbing one of them 37 times with an oyster knife. He receives a letter from the mother of one of the boys who was killed, and it affects him deeply — it’s a blow beneath the waterline.

“By what inevitable degrees,” Stanley Elkin asked in “The Dick Gibson Show,” his 1971 novel, “does bent become inclination, inclination tendency, tendency penchant, penchant disposition, disposition fate?”

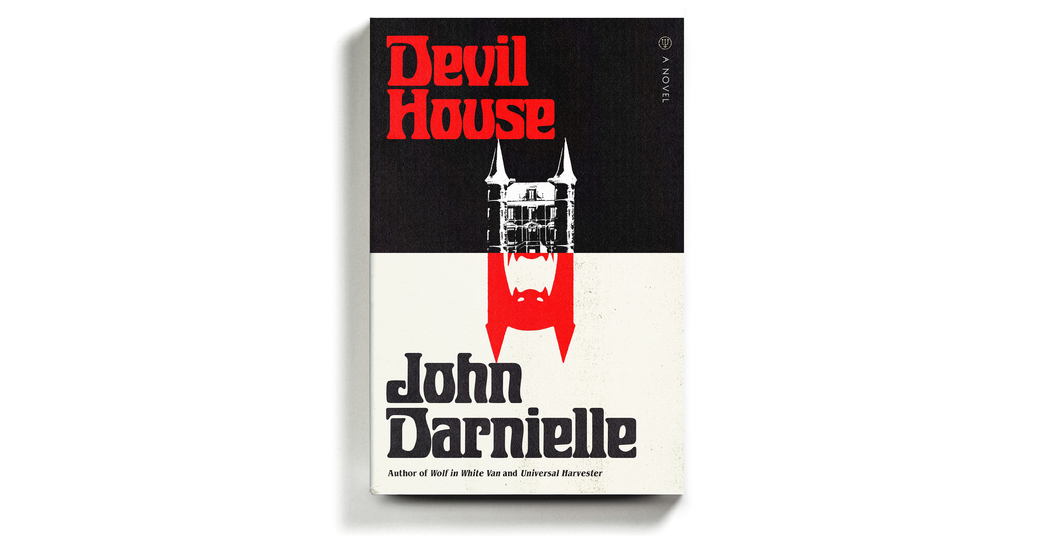

That’s a restating of one of the issues that animates “Devil House.” It’s never quite the book you think it is. It’s better.