The Museum of Modern Art’s lobby will glow this winter, not by the twinkling lights of the holiday season but the swirling datascapes of a digital artist whose popularity rose during the speculative frenzy around NFTs.

Last year, Refik Anadol plugged more than 138,000 images and text materials from the museum’s publicly available archive into a machine-learning model to create hundreds of colorful abstractions that he called “machine hallucinations,” selling them as NFTs, or nonfungible tokens.

It was the beginning of a quiet partnership between Anadol, a 37-year-old Turkish American artist, and the MoMA curators Michelle Kuo and Paola Antonelli — and it was a financial boon for both parties. Some of the blockchain-based artworks wound up selling for thousands of dollars, with the most exclusive one selling for $200,000. Within the fine print of the transactions was a note that the museum would earn nearly 17 percent of all primary sales and 5 percent of all secondary sales. For MoMA, struggling with pandemic attendance drop-off — from about three million in normal times to 1.65 million last fiscal year — growing a digital audience makes good financial sense.

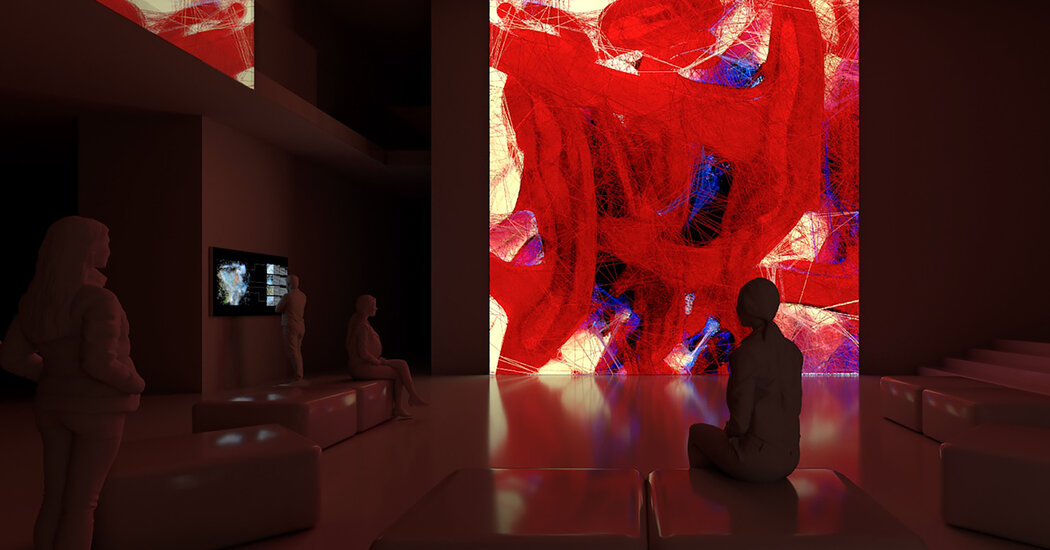

Now, the curators have invited Anadol to dig deeper into the MoMA archives for the new data-driven installation, “Refik Anadol: Unsupervised,” which will start Nov. 19 in the Gund Lobby and run through March 5.

“Being open to new technology is part of our responsibility,” said Antonelli, the museum’s senior curator for the department of architecture and design, who is known for guiding MoMA’s acquisitions of historical video games like Pac-Man and the @ symbol. “We are never jumping on new technologies, but rather realizing that we need to keep pace with the world.”

Until recently, most museums had spurned digital art collections in favor of the paintings and sculptures that still dominate their galleries. But after budgets tightened and attendance plateaued during the coronavirus pandemic, the industry has started to embrace artistic experiments involving blockchain, virtual reality and artificial intelligence programs. Curators want to connect with younger, tech-obsessed audiences and catch the interest of any crypto millionaires who might donate.

At the Guggenheim Museum, executives are hiring a new assistant curator for digital art that will be funded by LG, the electronics company, which is also paying for a $100,000 annual award to artists making “groundbreaking achievements in technology-based art.” Conservators are also exploring the possibility of uploading ownership records to the blockchain, which could help art historians researching the collection.

Naomi Beckwith, the museum’s deputy director and chief curator, said that while some trustees had been focused on the financial possibilities of NFTs, her curatorial team had a broader mandate to follow artists into the metaverse, buzzy shorthand for new online technologies.

“We have hit a critical point where the technology that’s available to artists has far outpaced what museums can offer in terms of resources. So we have to beef up,” Beckwith said. “If artists are working with technology, then we have to be able to hold it.”

Historically, museums have been reluctant to embrace technologies that might require conservation tools and curatorial expertise beyond the classical traditions of painting and sculpture. It took nearly a century after photography was invented for the artistic medium to receive its first museum exhibition in the United States. That 1910 show at Buffalo’s Albright Art Gallery was arranged to demonstrate that photography could be a visual form of artistic expression during an era when most people regarded cameras as documentary tools.

Things move much faster nowadays. Only 14 years after the blockchain was invented through the development of cryptocurrency, that same gallery, now called the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, will have an online auction that the curator Tina Rivers Ryan billed as the first survey of blockchain art by a major American museum. “Peer to Peer” will open in November with commissioned works by more than a dozen digital artists, including Rhea Myers, LaTurbo Avedon and Itzel Yard (known online as IX Shells).

The Fine Arts & Exhibits Special Section

A museum spokesman, Woody Brown, was careful to avoid saying that his institution was selling NFTs, preferring to describe the offerings as “digital artworks by artists who are engaged with blockchain technologies.” However, many of the artists included in the exhibition are known for selling NFTs and the show is being produced alongside Feral File, an NFT marketplace that also hosted the sale for Anadol’s collaboration with MoMA.

The sharp decline of the NFT market, with trading volume plummeting nearly 97 percent compared with record highs, is already starting to change the way digital art is branded. Some artists and curators are avoiding the term because of its association with speculation and scamming. Others complain that marketers used the abbreviation as a catchall over the past two years, incorrectly lumping together different types of digital art to take advantage of the bull market.

Christiane Paul, the Whitney Museum’s digital art curator, described the situation as a mixed blessing for her field of expertise. “On the upside, NFTs have generated more interest and awareness for digital art,” she said. “But one of my pet peeves is how people now equate digital art with JPEGs and spinning little GIFs when it’s a medium that has a 60-year-long history that consists of everything from algorithmic drawings to internet art.”

Paul was recently promoted after nearly 20 years as an adjunct with the Whitney. What changed? NFTs.

“Usually I had to sell the idea of digital art to the upper administrative levels,” she said. “Now trustees are coming to me and asking if the Whitney should be in the metaverse.”

Paul has used her expanded position to advocate more digital art in the museum, which commissions works annually through its Artport program. She said her job now was to fill gaps in the museum’s collection, starting with the early days of computer drawings in the 1960s by artists like Manfred Mohr and the software experiments of the 1980s.

She said the museum has already collected several NFTs, including work from Eve Sussman’s series “89 Seconds Atomized,” which fractionalizes the artist’s video “89 Seconds at Alcazár” into 2,304 unique works that can be reassembled by collectors.

The curator said her approach was cautious. “We see NFTs as a natural extension of artistic practices in the digital field,,” Paul explained.

Some museums have been a little more adventurous, however, and the many initiatives MoMA had planned over the past year are starting to bear fruit.

With its share of profits from Anadol’s “machine hallucinations,” the museum hired a young associate named Madeleine Pierpont to help develop projects in the digital world. On a recent job posting, these included building membership and retail programs involving NFTs; facilitating artist blockchain projects; and researching partnerships with the crypto community.

In September, a foundation for the media mogul William Paley, who founded CBS, announced that it would auction a trove of artworks from his collection (including pieces by Picasso, Rodin and Renoir) for an estimated $70 million. The proceeds are supposed to help MoMA further expand its digital footprint, and the museum’s director, Glenn Lowry, did not rule out the possibility of purchasing NFTs with the money when asked by The Wall Street Journal.

“We’re conscious of the fact that we lend an imprimatur when we acquire pieces,” he told The Journal, “but that doesn’t mean we should avoid the domain.”

Over the past year, MoMA curators and trustees have quietly met with several blue-chip NFT artists like Mike Winkelmann (known as Beeple), Justin Aversano and Dmitri Cherniak. And during a recent event at the museum about how artists are using new web technologies, curators provided attendees with a free NFT they had commissioned by the artist Stephanie Dinkins.

Collectors have also made overtures. Ryan Zurrer, a venture capitalist in the crypto industry who owns one of Anadol’s NFTs, said he was interested in donating his edition to the museum.

Kuo, the MoMA curator, declined to discuss whether the museum would take Zurrer up on his offer. For now, she remains focused on installing Anadol’s living vortex of algorithmically generated visions in the museum’s lobby. The artist’s machine-learning program will continuously develop new images, combining information from the museum’s collections with real-time data from the environment inside and outside the building, including motion and climate.

“Refik is bending data — which we normally associate with rational systems — into a realm of surrealism and irrationality,” Kuo said. “His interpretation of MoMA’s data set is essentially a transformation of the history of modern art.”