CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — In the corner of a ground-floor gallery at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America sits a small plexiglass case, holding two cowboy hats.

One was the signature headgear of Flo Kennedy, the firebrand feminist lawyer and activist. The other belonged to Mildred Jefferson, a onetime president of the National Right to Life Committee.

One is brown suede, the other is white straw — a color contrast that might seem to symbolize the stark polarities of the abortion debate.

But “The Age of Roe,” a new exhibition here, aims to break down any simple understanding of how the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade has shaped America.

The show, in the works since 2020, was originally going to be called “Roe at 50.” But then the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in June struck down the constitutional right to abortion, and Roe was dead at 49.

“It was a weird time to be curating an exhibit,” Mary Ziegler, the exhibition curator, said in a telephone interview. “Since Dobbs — and I include myself here — it’s been a very emotional time. There’s been a lot of heat, and not a lot of light.”

Dobbs, Ziegler said, didn’t materially change much about the exhibition, beyond the title. And that title is meant to raise a question.

“Have we entered a new era, or not?” she said. “And if we have, what do we make of the old one?”

Debate over abortion may pervade our politics. But it’s a subject few museums have tackled. The Whitney Museum of American Art only recently acquired its first painting related to it. And at historical institutions, the charged politics around the issue may scare museum directors off.

Abortion, said Jane Kamensky, a professor of history at Harvard and the Schlesinger’s faculty director, is “an issue of lightning-rod intensity.” But questions of reproduction are central to the lives of women, she said, and to the library’s academic mission.

Read More on Abortion Issues in America

“If you live on the third rail,” she said, “what else can you do but try to use that electricity to illuminate?”

The exhibition represents more than an era in American history. It also reflects the continuing evolution of the Schlesinger, which dates its origins to 1943, when the suffragist Maud Wood Park donated her women’s rights collection to Radcliffe College, her alma mater. (Harvard College did not admit women until the 1970s.) Its collecting accelerated in the 1960s as both the women’s movement and the field of women’s history were exploding.

Today, the library’s 4,400 separate archival collections include the records of the National Abortion Rights Action League and the National Organization for Women, as well as the papers of advocates like Bill Baird, a pioneering reproductive rights activist who in 1965 opened one of the first abortion-referral clinics in the United States.

The Schlesinger has long held some papers from conservative women, like Jefferson, the anti-abortion activist (and the first African American woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School).

But in recent years, the library has pushed to broaden its holdings, looking beyond what Kamensky has called its predominantly upper-middle-class, liberal, “Acela corridor” perspective to include more radical women, women of color and conservative women.

The exhibition draws deeply from a huge collection acquired last year from the Sisters of Life, a Roman Catholic order founded in 1991 by Cardinal John Joseph O’Connor of New York to “promote life” and discourage abortion and euthanasia. Their holdings, largely amassed by the anti-abortion activist Joseph R. Stanton, had been kept in the order’s convent in the Bronx, with limited access for scholars.

Ziegler, who drew on the collection for her recent book “Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment,” helped bring it to the Schlesinger, after extended discussions.

“Historically, some archives, especially women’s archives, have tended to collect more from progressive organizations,” Ziegler said. For conservatives, she said, “this can create a feedback loop of mistrust.”

The Sisters of Life acquisition, Kamensky said, may be “challenging” for some in the archival community, including at the Schlesinger. But she said that a full understanding of the history of American women requires looking beyond the traditional liberal-feminist frame.

“With pro-life activism, we tend to understand it from the outside in,” she said. “The dynamics of our own moment shows us how insufficient that is.”

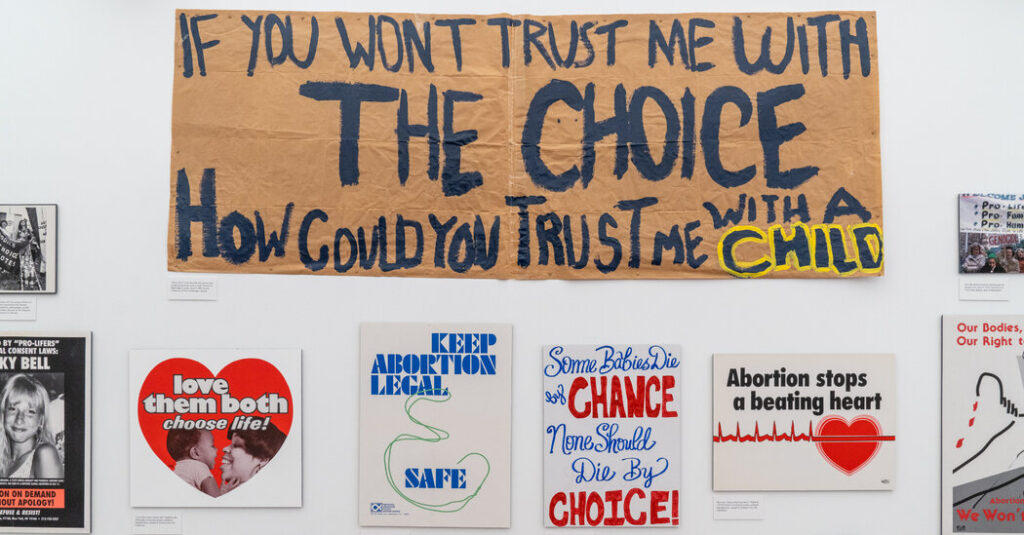

The material on display is mainly photographs, fliers, letters, clippings and signs. But on one wall, opposite the entrance, is a diptych that makes the bodily reality and pitched stakes of abortion viscerally clear.

To the left of a window, there’s a large painted cross. From a distance, it may seem to reflect religious objections to abortion. Come closer, and it turns out to be the “cross of oppression” Baird carried when he protested outside anti-abortion conventions.

To the right is a case with an array of obstetric instruments, along with boxes of the abortion medications that have increasingly taken the procedure out of clinics and into the home.

For some visitors, the wall text reads, the display may illustrate how abortion has become “safer, less time-consuming and less invasive.” Others may see “evidence of a crime or instruments of violence.” The potentially strong responses underline one of Ziegler’s main goals: keep the story personal, and let visitors react.

“The idea was to lift up voices you don’t usually hear, particularly people most intimately connected, and not editorialize a lot,” said Ziegler, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, who has contributed opinion essays to The New York Times.

The exhibition begins with a small display about abortion activism before Roe. During a tour last week, Jenny Gotwals, the library’s curator for gender and society, pointed out fliers with the now-familiar phrases “right to choose” and “a woman’s right.” In a nearby photo, a man at a 1971 anti-abortion protest in Massachusetts holds a sign reading “Abortion is Murder!”

“It’s really a snapshot of the rhetoric,” Gotwals said.

Wall projections of sometimes wrenching letters give different views of the experience behind the slogans. But one of the show’s most striking displays is entirely devoid of people.

Near the wall projections, an array of photographs show interiors from an abortion clinic in Hempstead, N.Y., established by Baird, a former pharmaceutical executive.

The empty waiting area bears an eerie resemblance to the living room on “The Brady Bunch.” Captions explain that the photos were taken in 1980, following repairs after a firebombing.

The exhibition also explores how the fault lines of race and class cut across the debate. Some items, like a statement from the Combahee River Collective, show how abortion has been seen as a means of autonomy and liberty for Black women, who have sometimes rejected the rhetoric of “choice” in favor of calls for “reproductive justice.” Other items denounce abortion as a tool of racial genocide, and a moral crime akin to slavery.

For many poor women, Roe itself was no guarantee of anything. A flier in Spanish advertises a vigil for Rosie Jiminez, said to be the first woman to die from an unsterile abortion after the passage in 1976 of the Hyde Amendment, which forbids Medicaid funding for abortions.

The show also captures how the party politics of abortion have hardened since the 1970s, when neither party, a wall text notes, had a clear position on abortion. The relationship between abortion and religion has also shifted.

Initially, the Roman Catholic Church (which fielded most early anti-abortion activists) “largely downplayed questions of faith around abortion,” a wall text says. And until the late ’70s, when white evangelicals embraced the anti-abortion cause, the Southern Baptist Convention supported a limited right to abortion.

In a small audiovisual gallery, a loop of archival footage brings some pungently theatrical blasts from the past. One clip shows Kennedy, the cowboy-hatted activist, leading a feminist “street walk” around St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, singing in-your-face (and unprintable) feminist anthems.

Another captures the moment in 1985 when Ronald Reagan called in to encourage a rally of anti-abortion protesters preparing to march from Los Angeles to Washington. “It’s a battle we’re going to win,” he said.

That pitched battle continues. But it’s undergirded, the exhibition notes, by a paradox. Even as party polarization around abortion has widened, public opinion has “remained strikingly stable, with most Americans supportive of a right to abortion with some restrictions.”

The show’s goal isn’t to change anyone’s mind, but to “replace dogmatism and ideology with curiosity and discovery,” Kamensky said.

“I hope people come away saying some version of ‘I didn’t know that,” she said.

You may also like

-

Capturing Stories, Connecting Worlds: The Journey of Cade Chudy and 4th Shore Productions

-

The Multidimensional Universe: A New Theory Unfolds

-

Lights, Camera, Impact: Antoine Gijbels’ Inspiring Videography Journey

-

Striking a Balance: Sophie Annaston’s Journey to Setting Boundaries in the Influencer World

-

Unlocking the Superpower of Critical Thinking: A Conversation with John Chetro Szivos