“Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts,” which opened this month at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is a classic holiday exhibition: family-friendly, frothy, not asking for much heavy lifting. And like that of the holiday season itself, its promise is a little overstated.

The exhibition traces, often in granular detail, the disparate elements of the European aesthetic movements that Disney animators, some 600 strong by the end of the 1930s, swept into its movies: French Rococo in “Beauty and the Beast” (1991); Gothic Revival architecture in “Cinderella” (1950), late medieval and Early Netherlandish art in “Sleeping Beauty” (1959), 19th-century Germanic Romanticism in “Snow White” (1937). All these stories originated in Europe, so the idea that the Disney machine rooted its visual interpretation in European art isn’t that much of a leap as, say, staging “Hamlet” in Y2K-era Manhattan.

As the title suggests, there are plenty of 18th-century French whorled gilt bronze candlesticks and treacly soft-paste biscuit porcelain figurines, but there’s also, by dint of the four Disney films included in the thesis, a good share of German, Netherlandish, and British examples, too. And those pieces, 60 in total and largely from the museum’s own collection, are outstripped more than two to one by items on loan directly from Disney: 150 pieces of concept art, works on paper, and film footage from the Walt Disney Animation Research Library, Walt Disney Archives, Walt Disney Imagineering Collection, and the Walt Disney Family Museum, which can make a viewer at the exhibition feel like Alice falling down the rabbit hole into a sponsored content post. (The Met says the exhibition is not underwritten by Disney, which I’m not sure makes this level of sanctioned corporate capriccio better or worse.)

The original “Beauty and the Beast” is a Rococo-era fairy tale written by French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, and later popularized by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont. (Jean Cocteau also made a popular film version, in 1946.) None of those three treatments featured anthropomorphized Boulle clocks and teapots with inexplicably English accents, understood to be the Disney triumph. The exhibition credits that flourish, however, to Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon, whose 1742 novel, “The Sofa, A Moral Tale,” tells the story of a man punished for his insincerity by having his soul condemned to inhabit sofas until he witnesses a genuine declaration of affection.

The exhibition explains this progenitor was unknown to Disney’s animators, and chalks the company’s invention up to serendipity. The Met tries to ground this section with a luscious red velour sofa (ottomane veilleuse) dated to around 1760, to show its Rococo roots.

While there is no bad excuse to look at a magnificent sofa or a richly adorned and miraculously complete Sèvres dinner service circa 1775, as is also on view here, its implied affinity with Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast” scullery duo of Mrs. Potts (transmogrified into a teapot) and her son Chip (a teacup) feels wan and contradictory. In fact, we learn that Disney’s animators found translating Rococo’s sinuous lines impossible, instead settling on a neutered stylistic expression. This is most disappointingly seen here in the cartoons’ costuming for its male characters: Rococo’s flamboyance was toned down so as not to alienate American concepts of masculinity. A historically correct Gaston would have delighted in an opulently embroidered waistcoat and ruffled jabot, rather than a solid colored V-neck whose only adornment was its plunging décolletage.

Beyond the visuals, there’s a tighter parallel between Disney’s goal of mass entertainment and Rococo’s superficial expression of pleasure that goes unexplored in the show (the exhibition is organized by Wolf Burchard, an associate curator at the Met). Both schools reflect the myopic optimism of their makers, Rococo, with its excesses of ornamentation, pastel color palette, and curvaceous shapes evoking youth and eroticism; Disney with its flattened ideas about good and evil and tidy endings. That optimism paid off better for Disney than Rococo, whose aristocratic decadence helped instigate the French Revolution.

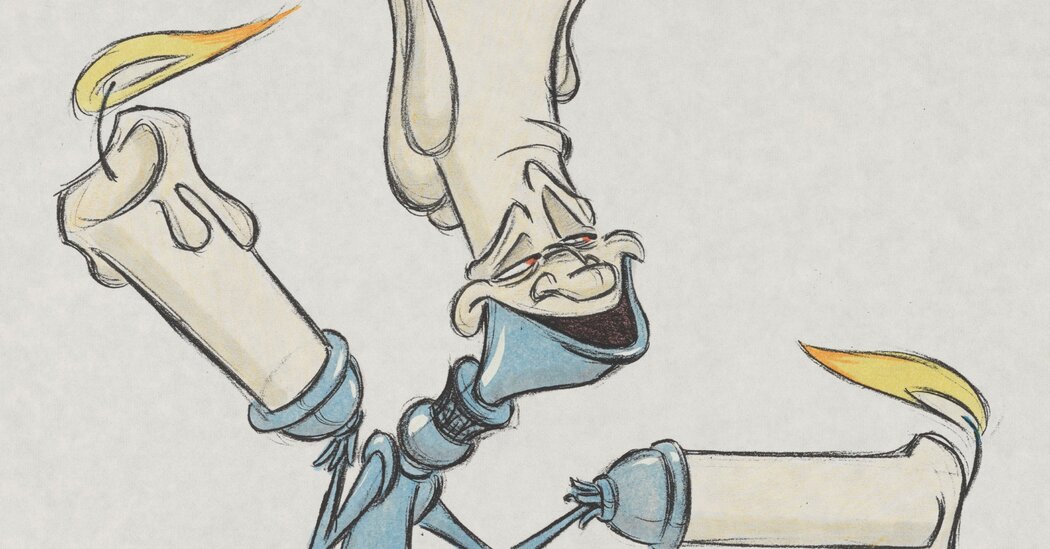

The exhibition settles for forced rhymes, like the suggestion that a roiling still life of a buffet by Alexandre François Desportes (1661-1743) possibly resembles the dancing-candlestick chorus line of “Be Our Guest,”and that the satyr presiding over the painting’s feast has a kinship with Lumière.

One of Disney’s clearest, most abiding influences is the Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, a 19th century historicist confection built in honor of Richard Wagner. It’s the direct model for the centerpieces of Disney’s theme parks around the world, and multiple iterations of its logo, so it’s surprising Neuschwanstein only makes a brief appearance toward the end of the exhibition. Though to be fair, “Inspiring Walt Disney, the Animation of the Burgenromantik” does not trip as easily off the tongue.

You would think Disney would object to the Met’s analysis of their appropriative techniques, but the exhibition is careful not to use the “A” word (the expansive catalog addresses this idea more fully). Disney’s films are “influenced” and “inspired” by European art rather than wholesale lifts of it. But the exhibition would be better served by locating Disney’s oeuvre in the continuum of lightly veiled theft that animates art history. There’s no shame in stealing, as Rubens’ copies of Titian upstairs attest.

Instead, the exhibition provides a fascinating if unintentional analysis of the particularly American compulsion to take European ideas and make them a little worse (café culture, bread, democracy), and the corporate compulsion to make those ideas a little worse still.

The most interesting of the Disney-supplied artifacts on view are the panels of concept art from its famed animators — Mary Blair’s vibrantly colored, almost abstract gouaches; Eyvind Earle’s deeply layered background paintings; Mel Shaw’s evocative soft pastels; and Kay Nielsen’s sumptuous preparatory sketches, all of which were largely junked or flattened, according to the exhibition, into Disney’s matte finish realism. They look totally foreign to their final counterparts, and one can’t help but fantasize about how richer those films could have been had they been faithful to their artists’ vision.

Is Disney’s output art? It’s not really a question that troubles the exhibition, but one that the exhibition insists on printing in big letters anyway, presumably to pre-empt criticism. In 1938, we learn in the show, when the Met accepted Disney’s gift of an animation cel from “Snow White” into its collection, Walt Disney cannily suggested many of the old masters he was joining would make fine employees, even as the man who was arguably the country’s largest employer of artists posed as the rube (“Well, take da Vinci. He was a great hand for experiments. He could have tinkered around to his heart’s content working for us … But don’t ask me anything about art. I don’t know anything about it.”).

Now as then, the Met positions its current inclusion of Disney in the same register of daring vision, as if Disney is still a vanguard animation studio and not the world’s largest conglomerator of entertainment I.P.

The self-consciousness isn’t necessary; Disney transcended the high-low debate a long time ago. A better question is whether a major art institution dedicating programming to a multibillion dollar corporate behemoth best serves a viewing public (the Met allows Condé Nast to do this once a year, too, of course, with its Costume Institute Gala).

By the time you’re spat out into the Petrie European Sculpture Court it’s hard to say whom this is all meant for. Devotees of the decorative arts will likely balk at the dilution of the form, much of which is on view elsewhere in the museum without commercial interruption; and it’s doubtful Disney completists, who can be rabid in their devotion, have a Rococo-shaped hole in their hearts.

“Children believe what you tell them and they do not call it into question,” goes the preface to Cocteau’s “Beauty and the Beast.” Certainly naïveté helps here, too. I watched a small girl in a tulle tutu try to scale a vitrine of Meissen porcelain statuettes by Johann Joachim Kändler, particularly enchanted with one group, a fox accompanying a singer on harpsichord. She was having a great time.

Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts

Through March 6, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Ave., (212) 535-7710, metmuseum.org.