UNIVERSAL CITY, Calif. — At the outset of the coronavirus pandemic, when film production came to a halt and recording studios shuttered, John Williams, the storied Hollywood composer and conductor, found himself, for the first time in his nearly seven-decade career, without a movie to worry about.

This, in Williams’s highly ritualized world — mornings spent studying film reels and improvising at his Steinway; a turkey sandwich and glass of Perrier at 1 p.m.; afternoons devoted to revisions — was initially disorienting.

But in the months that followed, Williams came to relish his freedom. He had time to compose a violin concerto, immerse himself in scores by Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms, and go for long walks on a golf course near his home in Los Angeles.

“I welcomed it,” Williams said in a recent interview. “It was an escape.”

Now the film industry is back in action, and Williams, who turned 90 on Tuesday, is once again at the piano churning out earworms — pencil, paper and stopwatch in hand.

But Williams, whose music permeates popular culture to a degree unsurpassed by any other contemporary composer, is at a crossroads. Tired of the constraints of film — the deadlines, the need for brevity, the competition with ever-blaring sound effects, the work eating up half a year — he says he will soon step away from movie projects.

“I don’t particularly want to do films anymore,” he said. “Six months of life at my age is a long time.”

In his next phase, he plans to focus more intensely on another passion: writing concert works, of which he has already produced several dozen. He has visions of another piece for a longtime collaborator, the cellist Yo-Yo Ma, and he is planning his first proper piano concerto.

“I’m much happier, as I have been during this Covid time, working with an artist and making the music the best you can possibly make it in your hands,” he said.

Yet the legacy of his more than 100 film scores — the “Star Wars,” “Jaws” and “Harry Potter” franchises among them — looms large, to say nothing of his fanfares, themes and celebratory anthems for the likes of NBC’s “Meet the Press,” “Sunday Night Football,” the Olympics and the Statue of Liberty’s centennial.

“He has written the soundtrack of our lives,” said the conductor Gustavo Dudamel, a friend. “When we listen to a melody of John’s, we go back to a time, to a taste, to a smell. All our senses go back to a moment.”

Williams’s music harkens back to an era of Hollywood blockbusters, when crowds gathered at theaters to be transported. He has excelled at creating shared experiences: instilling in every member of an audience the same terror about a menacing shark, conjuring a common exhilaration in watching spaceships take flight.

The pandemic has robbed Hollywood of some of that magic. But Williams’s admirers say his music, with its appeal across cultures and generations, is an antidote to the isolation of the moment.

“We need him more now than we’ve ever needed him before,” said Hans Zimmer, another storied film composer.

Williams — a fixture in the industry since the 1950s, with 52 Academy Award nominations, second only to Walt Disney, and five Oscars — recognizes that he might be the last of a certain type of Hollywood composer. Grandiose, complex orchestral scores, rooted in European Romanticism, are increasingly rare. At many film studios, synthesized music is the rage.

“I feel like I’m sort of sitting on an edge of something,” he said, “and change is happening.”

Born in New York, Williams became interested in composing as a teenager, entranced by the orchestral scores and books brought home by his father, a jazz percussionist.

After stints as a studio pianist in Hollywood in his 20s, he found work as a film and television composer, making his feature film debut at 26, in 1958, with “Daddy-O,” a comedy about street racing.

In the 1970s, Williams’s work caught the attention of Steven Spielberg, then an aspiring filmmaker searching for someone who could write like a previous generation of Hollywood composers: Max Steiner, Dimitri Tiomkin, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Bernard Herrmann.

“He knew how to write a tune, and he knew how to support that tune with compelling and complex arrangements,” Spielberg recalled in an interview. “I hadn’t heard anything of the likes since the old greats.”

The two began a partnership that has spanned a half century and more than two dozen films, including “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” “Schindler’s List” and “Jaws,” for which Williams’s two-note ostinato became a cultural phenomenon.

“When everyone came out and said ‘Jaws’ scared them out of the water, it was Johnny who scared them out of the water,” Spielberg said. “His music was scarier than seeing the shark.”

In 1974, when he was 42, Williams suffered what he called “the tragedy of my life” when his first wife, the actress Barbara Ruick, died suddenly.

“It taught me who I was and the meaning of my work,” he said, but added that the next several years were difficult, and he struggled as a single parent of three children with a busy career. “Star Wars,” which premiered in 1977, brought a new level of fame and marked the beginning of a four-decade-long project that has encompassed nine films, dozens of musical motifs and more than 20 hours of music.

George Lucas, the creator of “Star Wars,” said Williams was the “secret sauce” of the franchise. While the two sometimes disagreed, he said Williams did not hesitate to try out new material, including when Lucas initially rejected his scoring of a well-known scene in which Luke Skywalker gazes at a desert sunset.

“You normally have, with a composer, giant egos, and wanting to argue about everything, and ‘I want it to be my score, not your score,’” Lucas said. “None of that existed with John.”

Williams’s career as a conductor also took off. In 1980, he was chosen to succeed Arthur Fiedler as the leader of the Boston Pops. Over the next 13 years in the position, he worked to promote film music as art, and forged friendships with leading classical artists.

In 1993, when he was working on “Schindler’s List,” he called the renowned violinist Itzhak Perlman. “I hear a violin,” he said, according to Perlman. To this day, Perlman added, the aching theme from that film remains the only piece that audiences specifically request to hear at his concerts.

Perlman said Williams had a talent for conveying the essence of disparate cultures: evoking Jewish identity in “Schindler’s List,” for example, or Japanese traditions in “Memoirs of a Geisha.”

Five Movies to Watch This Winter

“His music has a fingerprint,” he said. “When you hear it, you know it’s John.”

Williams’s concert works, more abstract than much of his film music, have been less widely embraced. But Ma, for whom Williams has written several pieces, said curiosity and humanity anchored his works. In 2001, moments before Ma was to begin a recording session of “Elegy,” a piece for cello and orchestra, he recalled that Williams told him he had written the music in honor of two children who had been murdered.

“I think of him as a total musician, someone who has experienced everything,” Ma said. “He knows all the ways that music can be made.”

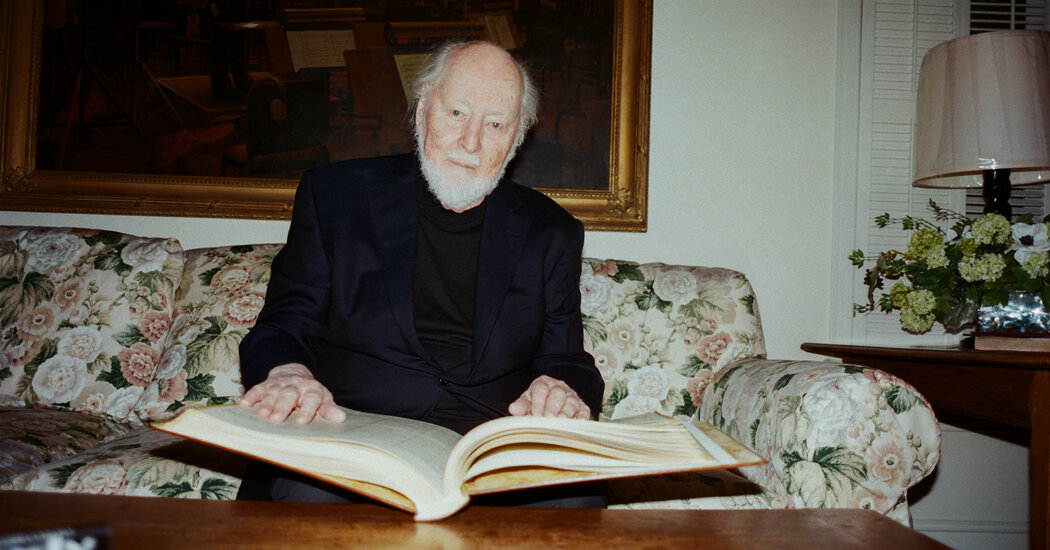

Inside his studio on the back lot of Universal Studios Hollywood, Williams is surrounded by mementos: a miniature bust of Beethoven, vintage movie posters chosen by Spielberg and, on a coffee table, a yellow bumper sticker reading, “Just Say No.” A model of a dinosaur, a nod to “Jurassic Park,” watches over the piano.

At 90, he is astute and energetic but soft-spoken, looking much the same as he has the past two decades: black turtleneck, faint eyebrows and a wispy white beard.

This year, he will complete what he expects to be his final two films: “The Fabelmans,” loosely based on Spielberg’s childhood, and a fifth installment in the “Indiana Jones” series.

“The Fabelmans” has been particularly emotional, he said, given its importance to Spielberg. On a recent day, he recounted, the director wept as Williams played through several scenes on the piano.

Williams said that he expected “The Fabelmans” would be the pair’s final film collaboration, though he added that it was hard to say no to Spielberg, whom he considers a brother. (Spielberg, for his part, said that Williams had promised to continue scoring his films indefinitely. “I feel pretty secure,” he said.)

At the end of his film career, Williams is making time to pursue some longtime dreams, including conducting in Europe. His works were once considered too commercial for some of the great concert halls. But when he made his debut with the Vienna Philharmonic in 2020, players asked for photos and autographs.

The violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter said she was disappointed that there had been skepticism about his music.

“Everything he writes is art,” said Mutter, for whom Williams wrote his second violin concerto, which premiered last year. “His music, in its diversity, has greatly contributed to the survival of so-called classical music.”

And his peers say he has helped establish, beyond doubt, the legitimacy of film music. Zimmer, who wrote the music for “Dune,” said he is “the greatest composer America has had, end of story.” Danny Elfman, another film composer, called him “the godfather, the master.” Dudamel drew comparisons to Beethoven.

Williams is more modest, describing himself as a carpenter. “I don’t know if it’s a passion,” he said of composing, “as much as an almost physiological necessity.”

He said he still gets a thrill when people tell him that his music has been formative in their lives: He was delighted several years ago when Mark Zuckerberg, the chief executive of Meta, said he had insisted on playing “Star Wars” at his bar mitzvah, over his parents’ objections.

Williams said he tries not to fixate on age, even as hundreds of ensembles around the world — in Japan, Australia, Italy and elsewhere — host concerts to mark his birthday. And he said he does not fear death; he sees life as a dream, at the end of which we awaken.

“Music has been my oxygen,” he said, “and has kept me alive and interested and occupied and gratified.”

Williams recalled a recent pilgrimage to St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, Germany, where Bach once worked as a cantor. He listened intently as a pastor described the efforts to protect the great composer’s remains during World War II; he marveled at the dedication to preserving Bach’s legacy.

On his way out of the church, he paused. An organist was filling the grand space with the hymn-like theme from “Jurassic Park.”

Williams, beaming, turned to the pastor.

“Now,” he said, “I can die.”