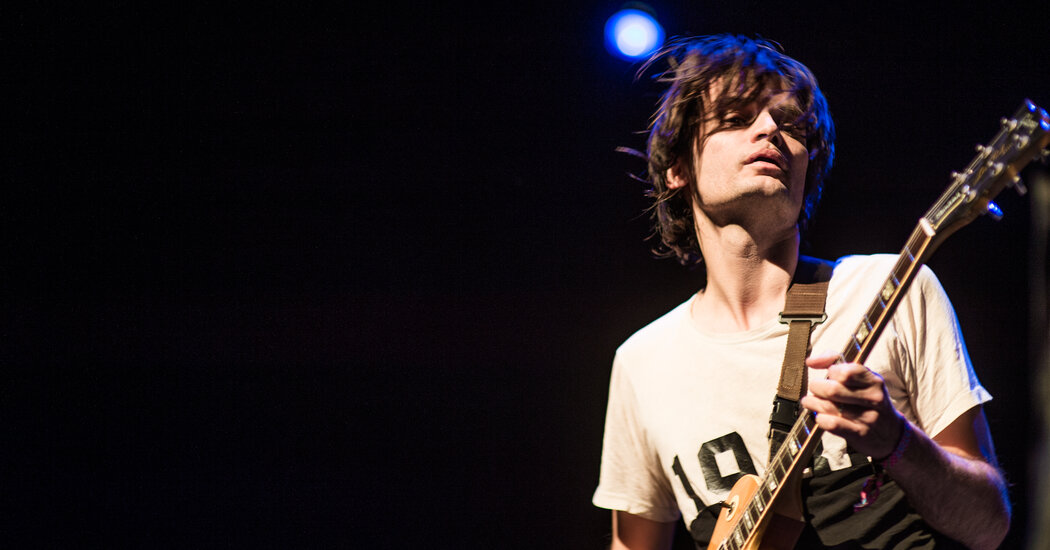

Jonny Greenwood had long since achieved global fame, as the lead guitarist of Radiohead, when he ventured into scoring films nearly 20 years ago. To some, this seemed at first like a side hustle, something to keep Greenwood occupied between albums and tours.

But over the last decade in particular, it’s become clear that is not the case. With 11 scores to his name, including two — for Jane Campion’s “The Power of the Dog” and Pablo Larraín’s “Spencer” — that may figure in this year’s Academy Awards race, what was once a subsidiary career now vies for pre-eminence with Greenwood’s day job.

As he has moved further into film, he has also achieved some prominence as an orchestral composer, with his concert music often fueling his soundtracks. In a recent interview with Alex Ross of The New Yorker, Greenwood described some of his durable strategies, including the use of octatonic scales, which he said can lend “a nice, tense sourness in the middle of all of the sweetness” of a scene.

But if some of his inspirations have remained constant — with modernist composers like Olivier Messiaen and Krzysztof Penderecki remaining steady fascinations — he has also evolved over time. Here are some highlights from his past two decades of writing for orchestras and films.

‘Bodysong’ (2003)

Greenwood’s first soundtrack effort is modest in its ambitions but confident in its execution. It doesn’t offer full-throated orchestral material or directly invoke the likes of Messiaen or Penderecki. Instead, it is more closely associated with the avant-electronica of “Kid A” and “Amnesiac,” Radiohead albums from just before. Yet “Bodysong” makes for an effective, ear-catching album. And some tracks are early templates when it comes to Greenwood’s skill at merging disparate styles, as when the opening jazz combo sound of “Milky Drops from Heaven” is overtaken by whirling tendrils of electronic music.

‘Popcorn Superhet Receiver’ (2005)

This work heralded Greenwood’s leap into classical music — complete with tightly coiled string clusters inspired by Penderecki. But Greenwood’s own melodic style, simultaneously swooning and full of unease, is here, too. It’s the piece that inspired the film director Paul Thomas Anderson to first contact Greenwood, and hearing “Popcorn” in full, you understand Anderson’s early confidence in this composer’s abilities.

What to Know About ‘The Power of the Dog’’

“The Power of the Dog,” Jane Campion’s simmering Western drama based on a 1967 novel by Thomas Savage, is currently streaming on Netflix.

‘There Will Be Blood’ (2007)

This was the project that Anderson wanted Greenwood for. It uses parts of “Popcorn Superhet Receiver,” making it ineligible for an Oscar, but adds some new music that helps render the film’s pressure-cooker atmosphere as something seductive. Like “Prospectors Arrive,” with piano, strings and the ondes Martenot in a gorgeous blend of instrumental colors. The Copenhagen Philharmonic later recorded a string orchestra suite culled from the soundtrack.

‘48 Responses to Polymorphia’ (2011)

The original incarnations of “Overtones” and “Baton Sparks,” from Anderson’s 2012 film “The Master,” can be heard in this orchestral work. That self-borrowing resulted in another round of Oscar ineligibility, despite the soundtrack’s excellent original tracks, like the harp-driven “Alethia.” And once again, the original orchestral piece is impressive on its own. Taking as its start the lush final chord of Penderecki’s “Polymorphia,” Greenwood pushes into more firmly Romantic territory than in “There Will Be Blood.” (Don’t worry, though: There’s still plenty of string noise.)

‘Inherent Vice’ (2014)

Anderson’s adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s noirish novel offered an opportunity for Greenwood to broaden his film-score palette. The song “Spooks” has its roots in an as-yet-unreleased Radiohead track, but the most winning feature for guitar here is “Amethyst” — a piece that combines folky strumming and droning background chords to ultimately joyous effect. It goes with a part of the ending that’s legitimately happy — not a regular feature of either Anderson’s or Pynchon’s work.

‘Water’ (2014)

This orchestral work fits well alongside the score for “Inherent Vice.” You can hear in it some scalar patterns familiar from tracks like “The Golden Fang.” Yet this 14-minute piece (for an unusually outfitted string orchestra, including flutes, ondes Martenot and a tambura) is its own thing, perhaps because of inspiration from various Indian classical music traditions that Greenwood was immersed in around this time. After what amounts to a slow “alap” development section familiar from some raga styles, we get a climactic whirlwind tour through Greenwood’s overarching melodic design.

‘Phantom Thread’ (2017)

In an interview with the former New York Times chief classical music critic Anthony Tommasini, Greenwood described drawing inspiration from a wide variety of sources — including Benjamin Britten and Bill Evans — for the score of this Anderson film, set in the 1950s. But though the music lacks some of the obvious avant-garde touches of Greenwood’s past work, it’s still suffused with some of his signatures. A cascading piano riff from “The House of Woodcock,” for example, is a bit familiar when compared with the piano in the second half of “Prospectors Arrive” from “There Will Be Blood.” But the more sweetly arranged version here gives it an entirely new character.

‘You Were Never Really Here’ (2017)

If the score for “Phantom Thread” was uncharacteristically gallant, here is a return to electronically driven, sometimes discordant music, Greenwood’s second time working with the director Lynne Ramsay. Just as Joaquin Phoenix’s character stumbles through the plot without a full understanding of what he’s stepping into, so, too, does Greenwood’s score keep the listener off balance — thanks to rhythmic feints in quasi-dance tracks like “Nausea.” But it’s not all mysterious: “Tree Strings” and “Tree Synthesizers” help give the final act its surprising effect of release from trauma.

‘The Power of the Dog’ (2021)

A setting in the old-time American West? Menacing, droning strings? Is this score for Campion’s first film in 12 years some kind of retread of Greenwood’s neo-Western work on “There Will Be Blood”? Not at all. Touches here are particular to the waking-dream surrealism of Campion’s project. “Detuned Mechanical Piano” is a bit too refined (à la miniatures by Gyorgy Ligeti) to really be the work of a busted player piano. And the strummed locomotion of “25 Years” is a reminder of Greenwood’s guitar chops, which were heard on his score for “Norwegian Wood” (2010).

‘Spencer’ (2021)

Larraín’s film, starring Kristen Stewart, isn’t a conventional Princess Diana biopic. As Diana hallucinates her way through various royal obligations, Greenwood’s score delights in the way that the film hews closely to her perspective. A track like “The Pearls” starts off as a plausible imitation of decorum, with a string quartet shown onscreen in the entryway to a dining room. But as Diana loses her cool, so, too, does the musical material stretch beyond propriety. (Sure enough, the onscreen quartet responds to the interminable dinner with some thundering accents.) The pairing of improv jazz textures with the escape from courtly life is particularly well done on cuts like “Arrival.”