CHICAGO — Going out to dinner with Jose Abreu, the reigning winner of the American League Most Valuable Player Award, can be a challenge. At least it is for his teammates on the Chicago White Sox who try to pay their fair share.

“He always tries to pay,” third baseman Yoan Moncada said in Spanish. “You want to pay but you can’t.”

“You have to stop him,” left fielder Eloy Jimenez added. “He likes paying. Just because he is earning more doesn’t means he has to buy all the food.”

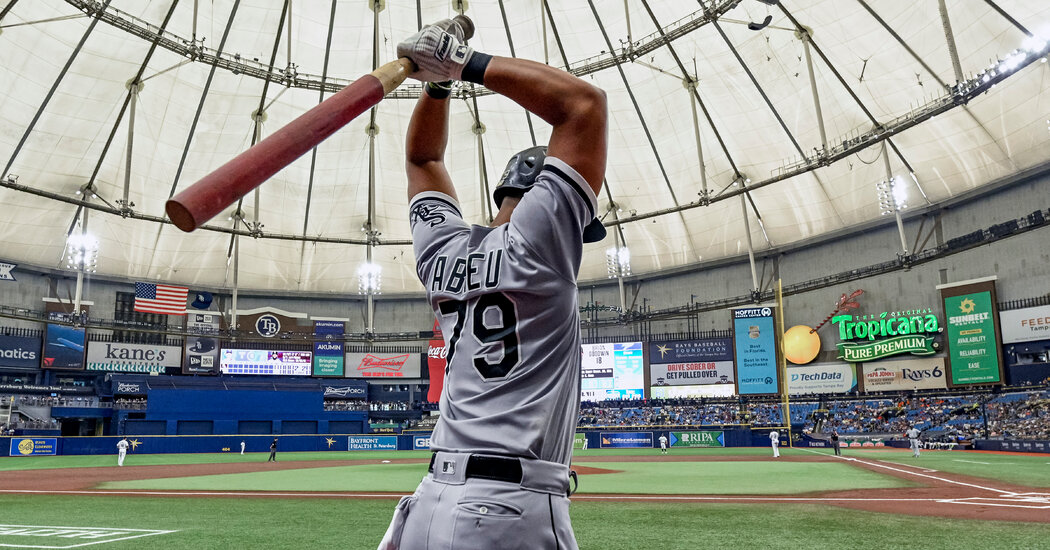

In many ways, on and off the field, the White Sox revolve around Abreu, their everyday first baseman since 2014. When they traded away mainstays like Chris Sale, Adam Eaton and Jose Quintana in 2017 to rebuild the roster and snap out of losing, they made Abreu a cornerstone. And as the White Sox have been reborn as one of the most exciting teams in baseball, and will soon claim their first A.L. Central crown since 2008, Abreu, 34, has remained exactly in the same spot — a run-producing slugger in the heart of the lineup and a team leader in the clubhouse.

“Through the early parts of this process, I said a few times that we probably value Jose more than other teams do, simply because we’ve had the benefit of seeing the impact he has in the clubhouse,” White Sox General Manager Rick Hahn said.

“And certainly everyone can see what he does on the field and the value on the offensive and defensive production. But we sort of boost that up a little bit because we know how he essentially role models exactly what we want guys to be when they wear a White Sox uniform.”

Like many Cuban baseball players fleeing to chase their major-league dreams, Abreu endured a harrowing defection to come to the United States. In 2013, he left on a boat to Haiti from Cuba, where he had starred for the Elefantes de Cienfuegos of Serie Nacional and made about $20 a month. On his flight from Haiti to Miami, where his six-year, $68 million contract with the White Sox awaited, Abreu has said he went to the airplane bathroom, ripped out the first page of the fake Haitian passport that bore his photo and fake name, and washed it down with the help of a beer.

Quickly, the 6-foot-3, 235-pound Abreu became a vital part of Chicago’s lineup. He was an All-Star and a Silver Slugger in his first season, and won the A.L. Rookie of the Year Award for hitting .317 with 36 home runs and 107 runs batted in. He has been as reliable as any player in baseball since.

Through Friday, only one person had more R.B.I. than Abreu (782) since the start 2014: St. Louis Cardinals third baseman Nolan Arenado (807). Only two people — Carlos Santana and Charlie Blackmon — had played in more games than Abreu’s 1,101 in that span. He once explained that his mother, whom he left behind in Cuba when he defected, is unhappy whenever he is not in the lineup.

Other than his injured 2018 season and the coronavirus pandemic-shortened 60-game 2020 season, Abreu has hit at least 25 home runs and driven in at least 100 runs each year while playing every day. In an era of modern baseball where traditional measuring sticks such as R.B.I. have been de-emphasized over more precise advanced metrics, Abreu has excelled at driving in runs.

“They devalue everything at this point,” White Sox shortstop Tim Anderson, 28, said. “They devalue batting average, R.B.I. They just want homers. But the guy has been consistent since he got here and he just continues to work and get better the older he gets. Behind the scenes it’s totally different from what people see. He actually works and works and works.”

Last year, Abreu was named the A.L.’s M.V.P. for hitting .317 with 19 home runs and 60 R.B.I. as he guided the White Sox, who haven’t won a World Series since 2005, to their first postseason berth in 12 years.

Through Friday, he was hitting .263 with 29 home runs and 111 R.B.I., his third straight season leading the A.L. in run production. He has played in 140 of his team’s 147 games, overcoming nicks and bruises and hit-by-pitches that might send others to the injured list. (Opponents try to neutralize Abreu, who stands close to the plate, by pitching him in, and thus he had been hit 19 times through Friday, fourth most in baseball.)

“He gets himself ready, no matter how he’s aching or tired or whatever, and takes the assignment,” White Sox Manager Tony LaRussa said. “He gets himself ready to play and he plays with great enthusiasm and toughness. That’s a special kind of dig-deep toughness that goes beyond his talent.”

After colliding with Kansas City Royals third baseman Hunter Dozier in May, Abreu suffered a black eye, a face laceration and a bruised knee. He tried to play the second game of the doubleheader that day and was overruled by LaRussa and the medical staff, but he was back in the lineup the next day.

“It’s been time and again where there’s been situations where you think this guy is going to to be down for potentially an extended period of time, and he seemingly wills himself back to label health,” Hahn said. “It’s remarkable.”

Although Abreu declined to talk (“sorry brother,” he said in Spanish), his teammates and coaches said what they appreciated the most about him was his consistency: as an everyday player, as a hitter who can slow his heart rate in key moments, and as a quieter example to a young and boisterous team.

Anderson, another key centerpiece of the White Sox roster, said before and during games he asks Abreu for his plan against opposing pitchers and adapts it for himself. Infielder-outfielder Leury Garcia, who has played with Abreu since 2014, said he will often show up to the team’s spring training facility in Arizona at 6 a.m. only to discover Abreu showed up an hour earlier to lift weights.

On several occasions after long games, starter Lucas Giolito said he was on his way out when he spotted Abreu lifting weights or hitting in the indoor batting cages well after midnight because he was displeased with his at-bats that night.

“He’s one of the guys that when I look back on my career, I’m going to feel very fortunate to share the locker room with him for a number of years,” said Giolito, who along with All-Stars Lance Lynn and Carlos Rodon, forms a rotation that has been among the best in baseball. “The loyalty he has to this team, it’s pretty unmatched.”

Abreu has repeatedly said that he wants to finish his career with the White Sox. After his initial deal expired following the 2019 season, he agreed to a three-year $50-million contract.

“The last time he was a free agent, Jose said, ‘Even if they don’t re-sign me, I’m going to sign myself back here,’” Hahn said, before laughing. “And Jerry Reinsdorf, our owner said, ‘I don’t want Jose ever playing a game in another team’s uniform.’ And I pointed out this probably is not how you teach negotiation in college negotiation classes. But I won’t be surprised if a similar mentality is in play the next time.”

For Abreu, the White Sox are a perfect fit. The team has a long history of acquiring Cuban players — starting with a trade for outfielder Minnie Minoso, who was considered the first Black Latino star in the major leagues in 1951 — and Abreu has carried on that torch with pride.

So when the White Sox traded for Moncada, a former teammate of Abreu’s in Cuba, in July 2017, Abreu insisted on picking him up from the airport instead of the team sending a car. Abreu has taken Luis Robert, another Cuban; Moncada and Jimenez, who is from the Dominican Republic, under his wing and calls them his sons — and the group of players in their mid 20s have blossomed with the White Sox.

When Romy Gonzalez was called up to the major leagues this month, he said Abreu approached him on his first day with the team and told him, “If you ever need anything, let me know.” And over the coming weeks, Abreu and Gonzalez, a Cuban American raised in Miami, have talked more, including about their shared heritage.

“He’s always giving us wisdom and taking care of the entire team, especially the younger players without much experience and who don’t know a lot about how things are here,” Robert added.

After four White Sox players were named All-Stars in July, closer Liam Hendriks said Abreu got each of them — Anderson, Lynn, Rodon and himself — a nice bottle of liquor signed by the team. Although Hendriks said he can’t drink it because of a liver condition, he appreciated Abreu’s thoughtfulness and will display the memento on his mantle at home. And perhaps in the postseason, Abreu can finally be paid back.

“He takes care of us,” Hendriks said. “And now we’re hoping that we can bring him back some glittery jewelry at the end of this season.”