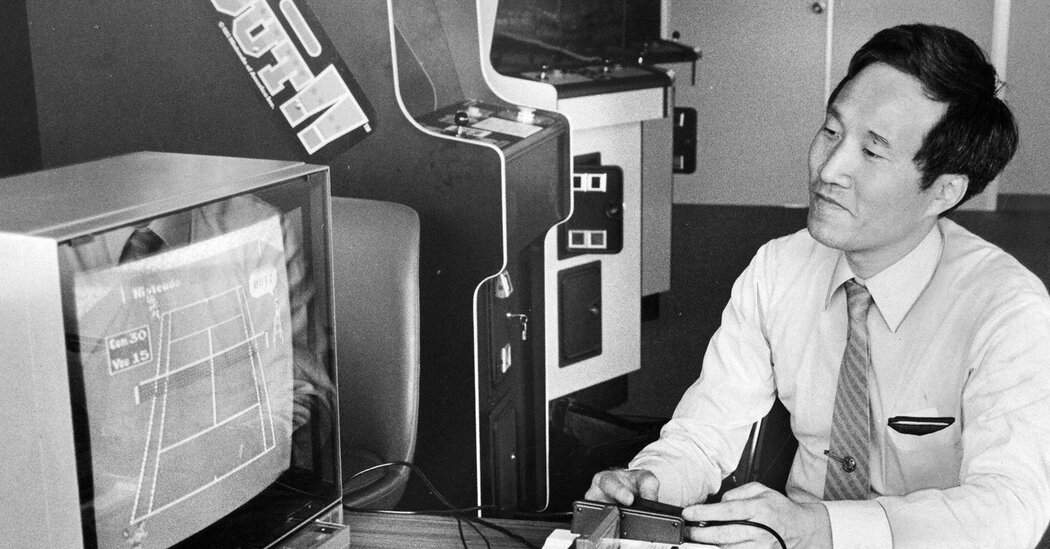

TOKYO — Masayuki Uemura, an engineer who developed the Nintendo Entertainment System, which helped start a global revolution in home gaming and laid the foundation for today’s video game industry, died on Dec. 9. He was 78.

His death was announced by Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan, where Mr. Uemura led the Center for Game Studies. No other details were given.

Video game consoles had a moment of popularity in the early 1980s, but the market collapsed because of shoddy quality control and uninspiring software that failed to provide the thrills of arcade hits like Pac-Man and Space Invaders. Truckloads of unsold game cartridges ended up in landfills, and retailers decided that home gaming systems had no future.

But in 1985, the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System in the United States changed the industry forever. The unassuming gray box with its distinctive controllers became a must-have for an entire generation of children and prompted Nintendo’s virtual monopoly over the industry for the better part of a decade as competitors pulled out of the market in response to the company’s dominance.

Mr. Uemura was the brains behind the Nintendo system, which was released in Japan in 1983. He also helped create its successor, the Super Nintendo, as well as other lesser-known products for the company.

“Nintendo succeeded in the United States because of the quality of its software, but that software never would’ve made it into the hearts of gamers without the hardware that Uemura created,” said Matt Alt, whose 2020 book, “Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World,” chronicles the rise of Nintendo.

“He was a true titan and architect of the global game industry,” Mr. Alt added in an email.

The machine made Nintendo one of the most profitable companies in Japan, and the games it ran, like Super Mario Brothers and The Legend of Zelda, have become classic franchises.

Its runaway success also established the video game console as a viable product and led to the development of today’s $40 billion console gaming market.

Masayuki Uemura was born on June 20, 1943, in Tokyo. His father, a kimono merchant who later owned a record store, moved the family to Kyoto (the home of Nintendo), hoping to avoid the bombing raids that ravaged Japan during World War II.

As a child, he showed an interest in technical pursuits. He built his own radio from components purchased for him by a student who was boarding with his family, Mr. Uemura said in an interview with Hitotsubashi University in 2016. He earned money carrying bundles of firewood down from the mountains around Kyoto and built his own pachinko machine, a game that resembles a fusion of slots and pinball.

After graduating from high school, he studied electrical engineering at Chiba Institute of Technology with the goal of designing color televisions.

He was working as a salesman at Sharp in 1971 when Gunpei Yokoi, the head engineer at Nintendo at the time, recruited him to join the company. It was then a minor maker of playing cards and other traditional Japanese games, with an ambition to create innovative new toys.

Mr. Uemura was inspired by Nintendo’s serious approach to play. But he had another motive for taking the job: He had recently married, and Sharp was planning to send him to the United States without his wife.

His decision to stay in Japan was transformative, both for himself and for Nintendo.

In 1981, when Nintendo was riding high on the popularity of the arcade game Donkey Kong in the U.S. market, the company’s president at the time, Hiroshi Yamauchi, asked Mr. Uemura to create an affordable entertainment system that would bring the arcade experience home.

The result was a red and white box known as the Famicom, short for “family computer.” While other consoles had blocky graphics that stuttered and jerked, the Famicom had smoothly animated characters and backdrops, almost like a cartoon. Its version of Donkey Kong looked just like the one in the arcade. And unlike the other gaming systems that bleeped and blooped, it could play music.

At first, the console, with a price of 14,800 yen (about $65 at the time), received a lukewarm reception in Japan — just a few hundred thousand units were sold in the first year. In interviews decades later, Mr. Uemura admitted that he had been skeptical that the Famicom would ever succeed. The early version of the system had been riddled with problems: Among them, the controllers had square buttons that tended to become stuck.

He had his first inkling of the system’s potential when his son told classmates that his father was the machine’s designer, and children from around the neighborhood asked Mr. Uemura to make house calls to fix their consoles.

“There were so many requests that I had the realization ‘This thing is really selling,’” he told Weekly Famitsu magazine in 2013.

But the system didn’t truly take off until the introduction of Super Mario Brothers in 1985. Its thrilling gameplay, catchy music and design — inspired by Japanese animation — was like “gasoline on a fire,” Mr. Uemura told Nintendo Dream Web in 2013.

He then created an upgraded and redesigned Famicom for the American market, and it sealed the system’s success, transforming Nintendo into a giant not just of gaming but also of Japanese industry. By the early 1990s the company was using 3 percent of Japan’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity and making more money than all the American movie studios combined, the author David Sheff wrote in his book “Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World” (1993).

The company then asked Mr. Uemura to design yet another upgrade. In 1990, he delivered the Super Famicom, known as the Super Nintendo in the U.S. The machine sold more than 49 million units globally, cementing Nintendo’s reputation as the world’s most influential game company and one of the most successful entertainment businesses of all time.

Mr. Uemura retired from Nintendo in 2004 and joined Ritsumeikan University, where he was director of the Center for Game Studies until his death.

Information on his survivors was not immediately available.

In a 2013 interview with the video game website Polygon for the 30th anniversary of the Famicom’s release, Mr. Uemura said that working on the project had been transformative.

“I used to be just your typical office grunt,” he said, “but then I ran into toys, and that changed my outlook on life.”