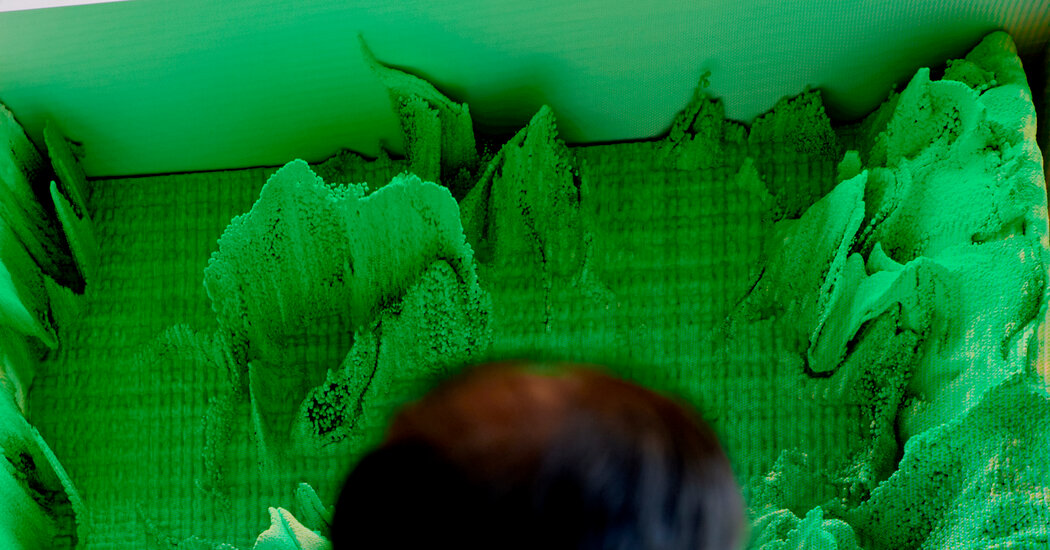

Color spills into the lobby of the Museum of Modern Art, radiating from a 3-D animation of sloshing, puffy liquid fizzing in ectoplasmic earth-tones and rancid pastels. This is Refik Anadol’s “Unsupervised,” and the roiling shapes greeting visitors from a 24-foot-high wall of LEDs are the museum’s collection of art, design and photography — analyzed, digitized, fed to an algorithm and returned as spectacular slurry.

Anadol, 37, is a digital artist known for using A.I. to turn piles of data into spectral, abstract visuals, often at huge scale. To do this, he has partnered with the likes of Microsoft, MIT and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. In 2018, for example, with Google’s help, Anadol projected mind-bending pictures based on the complete archive of the Los Angeles Philharmonic onto the exterior of Disney Hall. An upcoming show at Jeffrey Deitch in Los Angeles promises wavelike imagery stirred by observations of the Pacific Ocean.

This time, it’s MoMA’s collection behind the globs and blobs. Informed by nearly every object in the museum’s collection, “Unsupervised” automates a modernist notion of progress: input art history, output the next avant-garde. This context draws out some of the most interesting questions around “big data,” A.I. and creativity. How should we process the past? How can MoMA, the mausoleum of yesterday’s radical art, stay relevant? Not least, the impulse to make computers do something “artistic” speaks to our anxiety around what makes us human — if software can create art, then what’s left for us?

It’s a fearsome question. Anadol doesn’t answer it here. In his positivist vision, both progress and existential doubt have the breathless optimism of a TED Talk. Anadol describes his work as machine “hallucinations” and “dreams,” which is apt — the software interpolates the images it’s been given in a way that seems extra-real, vertiginous and wrong. In the argot of A.I. engineers, a program “hallucinates” when it generates falsehoods.

“Unsupervised” belongs to a burgeoning class of software known as Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN), where one part of the code tries to trick another part with imitations of whatever it’s been trained on, whether profile pictures or “Seinfeld” episodes. Here, software weaned on images and metadata — names, dimensions, materials — of MoMA’s holdings generates what it determines are new works of art. These creations are tweaked using real-time data like local weather and the motion of visitors, and displayed on the media wall in one of three morphing styles (officially, three distinct works): mottled blooms, skittering rays or molten Floam. A cosmic, swishing soundtrack issues from a pair of speakers.

In the last few years, as GAN-based programs like OpenAI’s Dall-E (get it?) and Google’s Deep Dream have become public, many users have tested the apps’ ability to reproduce or revise the greatest hits of art history, usually in the oversimplified way that “immersive experiences” riff on van Gogh or Kahlo.

The photographer Torbjørn Rødland, meanwhile, has used Dall-E to recreate masterpieces of photography and photohistory —from Henri Cartier-Bresson to William Eggleston — that reside at MoMA, but with a more critical eye.

His experiments don’t celebrate the technology, but demonstrate its shortcomings and sullenness. Try asking a text-to-image A.I. for “the decisive moment.” Whatever the technology sutures together will include the unsatisfying shadow of Cartier-Bresson, the street photographer who coined the concept — just as the contours of popular works appear when you type “Picasso” or “Kusama”; “trail cam” or “fisheye skateboard video.”

MoMA’s founding director Alfred Barr and first photo curator Beaumont Newhall started acquiring and exhibiting photography before the technical medium’s status as fine art was settled. The museum is doing the same with digital media, even as similar skepticism toward machine-made imagery echoes around A.I.-generated work. (Anadol and MoMA’s curators alluded to this reprise of history in a public conversation.)

This September, MoMA announced the sale of masterworks by Francis Bacon, Pierre Bonnard and others, under its care since 1990 (though not strictly in its collection), in order to endow its expansion into digital art. They’ve also dipped a toe into NFTs with alternate versions of “Unsupervised.”

Presumably, the project also incorporates provocative subjects — sex, violence, racism — the long and torturous 20th century as recorded by its artists. But “Unsupervised” is so abstract you’d never know that Faith Ringgold’s “American People Series #20: Die,” a bloody tableau of a 1960s uprising, may have provided shades of yellow, brown and red. In fact, MoMA says the software is designed not to produce recognizable figures. (Other public-facing GAN products similarly avoid potentially sensitive material.) It could be anything. The work’s enveloping abstraction scuttles the possibility of conceptual dignity offered by an institution founded to embrace challenging new art.

Then, every few minutes, the big screen flickers, as if straining, and the soothing colors turn into an array of charts tracking things like “energy difference” and the “current latent noise field.” Under “GAN video analysis” there are thumbnails of the jade lumps, gold lozenges and coal-colored squares “dreamed up” by the software. It’s like the way hacking is portrayed in a Hollywood film like “Jurassic Park,” with slick but simulated interfaces, so as not to bore audiences with the reality of coding.

At MoMA, home to some of the smartest art in recent history, these theatrical peeks under the machine’s hood feel patronizing. Does it really need to flicker? Is it working that hard?

On the contrary, “Unsupervised” suggests that creating the next avant-garde should be easy, if you have enough computing power. It’s as if A.I. can do our hallucinating and dreaming for us, minus the bad trips and nightmares. But the bad trips and nightmares are still there. “Unsupervised” is only a screen saver.

Refik Anadol: Unsupervised

Through March 5, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd St., Manhattan, moma.org.