SEOUL, South Korea — Itaewon, the Seoul district where 159 holiday revelers were crushed to death last Halloween, is neither silent nor haunted as the tragedy’s first anniversary looms.

The district’s main strip, a pedestrian alley lined with clubs and bars with names like Craft Hans, Jilhal Bros and Dead Man’s Fingers, was pulsating Friday night. Drinkers lined bars; stylishly dressed youths strolled; a man danced under a replica great white shark hanging from a bar ceiling.

Absent were decorations or references to the upcoming Halloween weekend, raising the prospect that this year the customary revels will be replaced by candlelight vigils.

“No predictions!” one bar owner said. “We are not too worried: We are a sports bar and will be packed for the Rugby World Cup.”

Others declined to speak.

“We don’t want to talk to media, we want to serve beer,” a bar staffer said. “The news is all bad news.”

Police, widely criticized for failing to appear in time last year, are now ubiquitous. Itaewon’s main road has one lane closed and is lined with police and emergency vehicles. Every alleyway entrance is manned by police and yellow-jacketed district office staff.

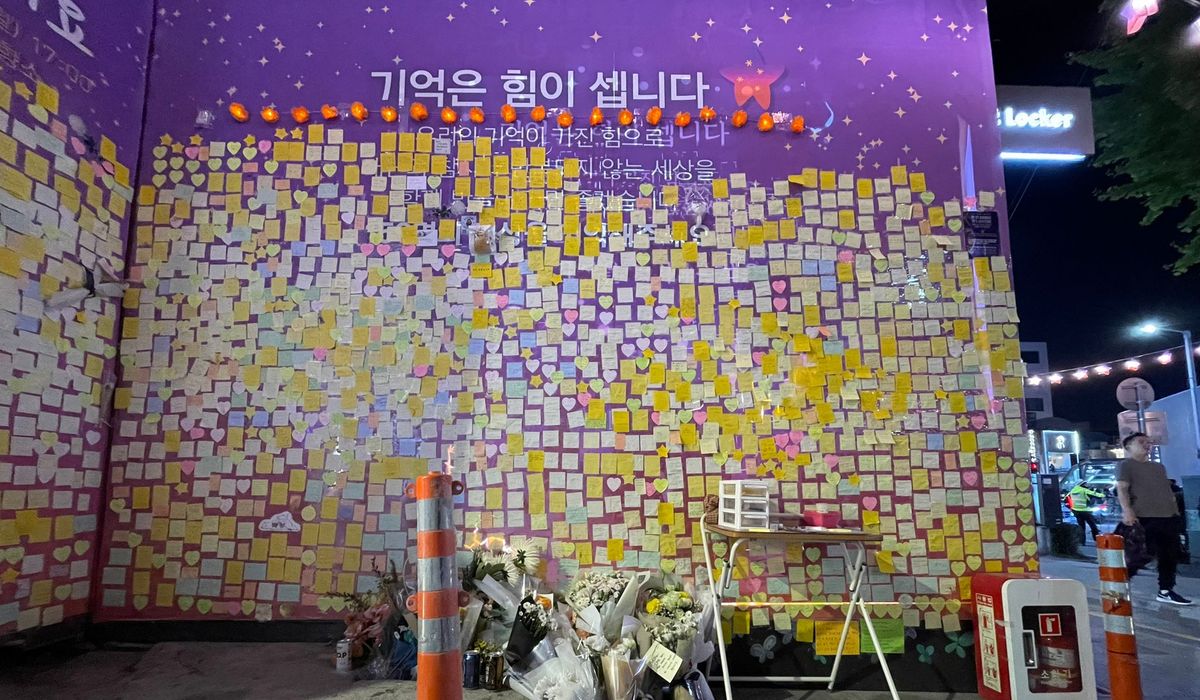

The side alley where the carnage occurred is still open to foot traffic, occupied by a restaurant, a club and a convenience store. But one wall is lined with somber Post-Its: “God bless your souls,” reads one.

Lee Ju-hyun, whose legs were injured in the crush and who still experiences trauma, will return.

“I will go to Itaewon, to the festival, this year,” Ms. Lee told foreign reporters Wednesday. “Itaewon and the Halloween festival are not guilty. Those responsible for crowd control are guilty.”

That responsibility, many say, lies with the government of conservative President Yoon Suk Yeol.

A monthslong police inquiry concluded that the tragedy was “a manmade disaster.” Sixteen public officials and two companies have been prosecuted, according to the nongovernmental organization Lawyers for a Democratic Society, and Seoul’s police chief remains under investigation by prosecutors. But an impeachment motion for the minister of public information and security was overturned in court.

Survivors, relatives and the lawyers group have unleashed a barrage of criticism over the aftermath of the tragedy. Accusing the government of mismanagement, lack of transparency and non-support and liability, they are demanding an independent investigation.

The hangover from the disaster presents a risk for a government that, next April, faces its biggest political test since taking power in 2022.

Night of horrors

Itaewon is Seoul’s most foreign-centric district — a character imparted by the decades-long presence of U.S. troops in the adjacent Yongsan military base. Other minority communities — expatriates, Muslims, LGBTQ people — flocked to the area, drawn by its freewheeling ambiance.

GIs relocated to Yellow Sea coastal bases in the 2010s, and Itaewon gentrified — it boasts a multi-story Gucci store and upscale boutiques — but never lost its abroad-at-home vibe.

It was renowned for staging South Korea’s best Halloween weekend. In 2022, there was an added frisson to the festivities as they came at the end of two years of social distancing restrictions applied during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On Oct. 29, an estimated 100,000 costumed and exuberant visitors packed the bar-lined alley, which runs parallel to Itaewon’s main street, the site of bus, subway and taxi stops. The disaster unfurled in a narrower, sloping side passageway connecting the street and the alley.

As crowds at the top massed, an “escalator effect” came into play: A compression of people funneled downhill. Revelers tumbled on top of one another in a tangle of bodies reportedly 15 feet deep. Pressure injuries and asphyxiation took a terrible toll.

Amid the nightmare, party music continued to blare. Neon lit the scene.

After casualty figures became clear, South Korea reeled. Angry questions were raised. Why was the packed district not policed more thoroughly? Why had crowd control measures not been prepared. and why had the emergency service response been so slow?

Conversely, some netizens accused partygoers of responsibility for their own misfortune, raising allegations of illicit drug use. Others complained that Halloween, a non-native festival imported from the United States, was to blame.

Political shocks

Shock waves jolted the body politic, with many drawing parallels with the 2014 sinking of the ferry Sewol, in which 299 people, mainly youths, died. Blame for that disaster hammered the first nail into the coffin of the administration of a previous conservative president, Park Geun-hye.

Memories were fresh two years later when Ms. Park was engulfed in a corruption/influence-peddling scandal. She was impeached, ejected from office, and jailed for almost five years.

A well-connected visitor to Seoul from Washington told The Washington Times this week of concerns among U.S. policymakers that 2022’s disaster fallout could have a similar impact on the fortunes of Mr. Yoon, who has cultivated stronger ties with the U.S.

Korean culture strongly champions victims, visible in politically charged memorials dotting downtown Seoul. One remembering Itaewon’s dead stands in front of City Hall. Across the street another memorializes the Sewol sinking. Down the street, another commemorates those allegedly killed by COVID vaccines. Behind the Japanese Embassy stands a statue of a “comfort woman.”

Mr. Yoon faces parliamentary elections next April, and a big loss for his party could leave him a political lame duck. Moreover, it’s feared the opposition Democratic Party could initiate impeachment proceedings if he is weakened significantly.

Error or negligence?

After the disaster, Mr. Yoon visited memorials while Premier Han Duck-soo briefed the media. The crux of the failure, Mr. Han said, was a gap in national crowd management systems.

Festival organizers are required to report to authorities prior to their event so that appropriate police assets can be deployed. However, Itaewon’s Halloween celebrations grew organically, out of the district’s bars and clubs. There was no single official organizer.

Hence, no special police presence was requested, Mr. Han said.

But there have also been allegations that the police were not in Itaewon in sufficient force because many were busy overseeing an anti-Yoon demonstration.

Yun Bok-nam of Lawyers for a Democratic Society says two companies of riot police — approximately 200 strong — monitored Itaewon in 2021. It is unclear, however, whether their role was crowd management or enforcing social distancing guidelines.

The only special police detachment in 2022 was carrying out anti-drug enforcement, fueling the anger of some of those who lost loved ones in the crash.

“Ruling party MPs have framed the victims as disorderly people, possibly involved with drugs,” said Yu Hyoung-woo, who lost a child in the tragedy. “The truth of that day is still unraveling.”

Callers to police lines, saying a disaster was underway, led to no action. The timing of the deaths remains unclear, as is the true scope of the victims.

“Victims include not just bereaved families, but survivors, those who took part in first aid, witnesses and local shopkeepers — everyone who suffered psychologically and physically,” Ms. Lee said. “All these people are being neglected.”

That sentiment is common.

“Government officials … never met the bereaved families of the victims or provided an official briefing on the tragedy,” said Mr. Yun. “Even when we approached them to talk, they have always ignored us.”

Nari Kim, an Austrian-Korean whose brother Hong Kim died last year, spoke tearily to journalists.

“It could have been prevented — no sufficient response came on time,” she said. “The government did not take it seriously, nor did they take responsibility.”

The association of bereaved family members plans a memorial event on Sunday.

𝗖𝗿𝗲𝗱𝗶𝘁𝘀, 𝗖𝗼𝗽𝘆𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁 & 𝗖𝗼𝘂𝗿𝘁𝗲𝘀𝘆: www.washingtontimes.com

𝗙𝗼𝗿 𝗮𝗻𝘆 𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗽𝗹𝗮𝗶𝗻𝘁𝘀 𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗮𝗿𝗱𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗗𝗠𝗖𝗔,

𝗣𝗹𝗲𝗮𝘀𝗲 𝘀𝗲𝗻𝗱 𝘂𝘀 𝗮𝗻 𝗲𝗺𝗮𝗶𝗹 𝗮𝘁 [email protected]