Calling your new public-affairs-comedy show “The Problem With Jon Stewart” is a provocation and a pre-emption. It sounds like the title of a think-piece that could have been written at any point over the last two decades, accusing the one-time “Daily Show” host of false equivalence, or partisanship, or naïveté.

Jon Stewart knows all this, the title says; he has even teed up your hack joke for you. You are free to title your review “The Problem With ‘The Problem With Jon Stewart,’” hit “Publish” and call it a day.

This kind of defensive self-deprecation can be, well, another problem with Jon Stewart. Even as he was reinventing political and media criticism on Comedy Central’s fake newscast (before “fake news” was rebranded), he had a ready deflection for both critiques and praise: We’re just a comedy show. As he told Tucker Carlson on CNN’s “Crossfire” in 2004 — a confrontation that only burnished his reputation as a 21st-century Howard Beale — “The show that leads into me is puppets making prank phone calls.”

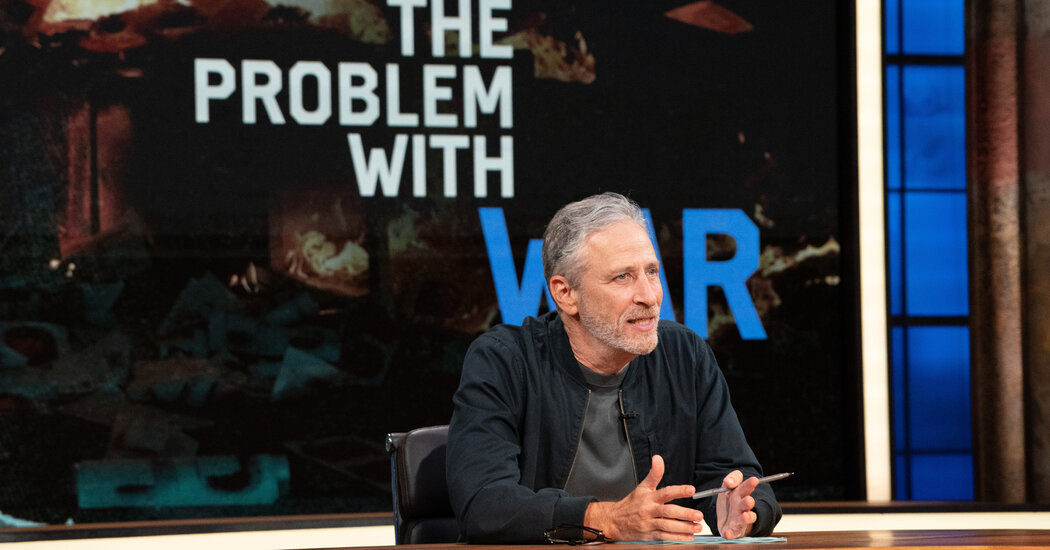

With “The Problem,” appearing every other Thursday on Apple TV+, this is no longer true, and not just in the literal sense that on streaming TV there are no lead-ins. In stature and in the new show’s spirit, he is now a pie thrower with a purpose.

Stewart has joined the ranks of personages like David Letterman, Oprah Winfrey and Barack Obama, creating high-minded programming for streaming TV. He is an éminence grise, though he makes his scruffy grise-iness a punchline. “This is what I look like now,” he tells his audience. “I don’t like it either.”

“The Problem” is his attempt to step up to that status and make a serious difference, albeit with one hand on the seltzer spritzer just in case. In its first two episodes, his show is “The Daily Show” but longer (around 45 minutes), more sustained and passionate in its attention and less funny — often intentionally, sometimes not.

The structure, Stewart says in the first episode, was inspired by a 2010 “Daily Show” in which a panel of 9/11 responders talked about their lingering health problems and Congress’s failure to approve help for them. Stewart became an advocate, on air and in Washington, for the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act.

“The Problem” teams up the satirist Stewart with the advocate Stewart. There are comic rants, taped sketches and the occasional off-color joke about the snake on the far-right symbol the Gadsden flag. But there’s also more room for other voices. Each episode centers on one issue — veterans’ health, gun violence, threats to democracy — and brings on panels of “stakeholders” affected by it.

The deep-dive approach is new for Stewart but not for the world of TV advocomedy he’s rejoining, shaped in part by “Daily Show” alums like John Oliver, Hasan Minhaj and Wyatt Cenac. (The resemblance to Cenac’s former HBO series “Problem Areas” was not lost on its host, who tweeted a clip of himself saying, “If you want somebody to take a Black guy saying something meaningful on TV seriously, you really need to have a white guy say basically the same thing right after.”)

The biggest value-add Jon Stewart brings, honestly, is Jon Stewart — his fame and ability to direct a spotlight. The panels are the most distinctive part of “The Problem,” drawing on the host’s later-era curiosity and empathy.

The first episode concentrates on veterans whose health-coverage claims are being denied by the government after their exposure to “burn pits,” in which troops incinerated toxic waste using jet fuel.

It’s agonizing to hear vets (whom, Stewart notes, politicians love to pay lip service to) talk of lung scarring and suicide attempts, saying they feel ignored and disposed. “Once you’re out, they do not care,” says the retired Army Sgt. Isiah James. An interview with Denis McDonough, the secretary of veterans affairs, shows an engaged, pressing interrogation style that took Stewart years to evolve.

Surprisingly, the comedy is the shakiest part early on. The first monologue hits air pockets of wan laughter — maybe the audience was unsure what to expect, maybe it was jarred by the contrast between the grim subject matter and the punch lines. Either way, it throws the momentum off. “I thought you people liked me!” Stewart jokes. They clearly do, but the feeling that a crowd is working to enjoy a monologue never makes for a great show.

The second episode is more caustically funny but also more scattershot. The topic is “freedom,” which means a tirade, à la vintage “Daily Show,” on anti-vaccinators who are prolonging the pandemic in the name of liberty, followed by a lengthy panel on the rise of authoritarianism in the United States and abroad. It’s more wide net than deep dive.

In both episodes, the comedy seems to be working on a parallel track to the journalism rather than building with it to a climax, as on Oliver’s “Last Week Tonight.” But the satire in the second episode hits harder, including a bit in which the actress Jenifer Lewis lambastes the protesters who have likened mask mandates to slavery: “They picked cotton. You just have to wear it.”

Did I like this better because it was closer to what I was used to from “The Daily Show”? Or because, like all viewers fist-pumping as their favorite late-night comic “destroys” somebody, I just like hearing someone acerbically agree with me?

Stewart, to his credit, seems uncomfortable with preaching to the like-minded, joking at one point that his audience is “a very broad-based selection of Upper West Side Jews.”

There’s a recurring self-consciousness about the limitations of comedy here, which comes up during an earnest discussion in the writers’ room. (These behind-the-scenes segments show a more diverse staff than on the old “Daily Show,” another oft-cited Problem With Jon Stewart.) The host gestures to a list on the whiteboard and cracks: “This is the problem with the comedy hybrid shows. The whole time we’re talking about this, I’m just looking at: No. 1 with an asterisk, ‘Snake penis.’”

On the other hand: Snake penis! It has always been a mistake for people, critics like me included, to treat Stewart’s serious aims and his jokes as if they were separate. Good comedy comes out of caring about something enough to think creatively about it. “The Daily Show” may not have set out to fix problems, but it gave viewers a toolbox, teaching them media literacy and bringing them the news with incision and analysis.

Of course, that only went so far. Stewart and Stephen Colbert’s “Rally for Sanity” before the 2010 midterms presaged an era of politics that rewarded demagogy and bad faith. (“We won,” he quips, when a guest references the rally on “The Problem.”) His last “Daily Show,” which included a valediction urging viewers to see through bluster and lies, aired the same night as the first presidential-primary debate of Donald Trump.

I can understand the pull of trying to proactively make a difference, to do something more than mere comedy. But for now — and talk shows need a long breaking-in period — maybe the best thing Stewart and “The Problem” can do is refine an entertainment sharp enough to draw the attention that he wants to redirect.

This, too, is a contribution. If “The Problem” results in a new equivalent of the Zadroga bill someday, great. But they also serve who only sit and mock.