Indeed, the rituals of courtly love were used to break Anne. The tight circle of poets and musicians and noblemen paying her obeisance was portrayed by her enemies as a ring of romantic assignations. Anne still hoped Henry was trying to “test” or “prove” her, Gristwood tells us, as she was escorted to the all-too-real Tower of London and the executioner’s block. The ever-chivalrous Henry, however, decreed that Anne should die by the sword — not the ax. Even as her show trial was in process, Gristwood notes, “the French swordsman hired to behead her was already on the way from Calais.”

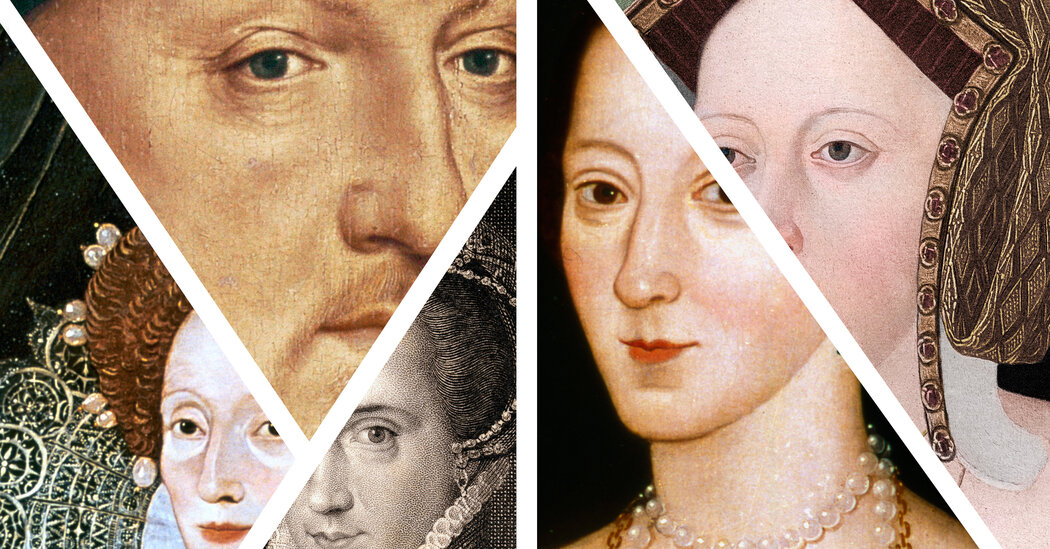

“The Tudors in Love” is at its best at these moments, when Gristwood’s prism of courtly love is smashed by the cruelty of power politics and we get the gripping — and heartbreaking — history of trapped royal women over more than a century. We learn how Anne’s predecessor, Catherine of Aragon, fights for dignity and identity from the moment she is shipped from Spain at age 15 as wedding chattel to marry Arthur, Henry’s older brother and heir to the throne. When Arthur dies five months later of indeterminate causes, Catherine endures seven years of “penurious uncertainty” in a foreign land without status or any clear future until, out of the blue, the 18-year-old Henry decides to solidify his legitimacy by marrying her.

We have seen and read so many depictions of Catherine as a sobbing victim that it’s refreshing here to be reminded that once married to Henry, she reigned over a cultured, respectful court, loved by her lusty young husband and influential with him in the international diplomacy of the period. Reading of the bravura of these days makes it all the more piercing when doomed pregnancies, followed by the birth of a mere girl, start to destabilize Catherine’s position and prepare the way for Henry’s explosive sexual solutions and her own abandonment.

Gristwood likewise manages to humanize Catherine’s Catholic daughter, “Bloody” Mary, usually remembered only for incinerating Protestant martyrs. Disinherited by her father, forcibly parted from her mother, Gristwood’s Mary burns with vivid emotional suffering as she endures two phantom pregnancies, a grotesque psychic replay of her mother’s maternal shame. “Still in pain, still with a swollen belly, Mary — pitifully, embarrassingly — was still also in hope, perhaps as the French ambassador heard early in May, the whole thing, swollen belly and all, had been the result of ‘some woeful malady.’” One of the saddest things about Mary was that her attempt to forge a marriage with Philip of Spain was conducted with all the artifice of courtly love — but she herself longed only for the real thing.

Better by far for a female monarch to abjure marriage altogether, revive Arthurian myth and be feted by her knights as an eternal belle dame sans merci. That’s the choice that Elizabeth I famously made, though for two decades of her 45-year reign there was constant pressure to make the right political match. As Gristwood writes: “The courtly lady was meant to be capricious, demanding, testing her lover’s utter fidelity. Caprice and demand were Elizabeth’s specialty.”

Deftly she played her favorites against each other, affording them intimacies of influence with boundaries it was hard at times to deconstruct. When Elizabeth was young and beautiful, the parade of suitors was easier to keep happy with inklings of consummation; but as the construct of the Virgin Queen solidified, one senses her aging knights wearying of the game that kept them vassals of her ego. Stray verses of her poetry, quoted by Gristwood, suggest her own emotional sacrifice to maintain the balance of power. “I am, and am not, freeze, and yet I burn/Since from myself my other self I turn.”

Elizabeth had chosen the mask and by the time she was in her 60s her raddled face, likely painted in white lead, her wig of orange curls, the corsets, stomachers and hoops that created the Gloriana myth were supposed to make her inviolable. But like so many fading beauties before her, she found herself suddenly vulnerable to the charm of a younger man on the make, the “ardent and athletic” Earl of Essex. There is a last terrible scene between them after he falls from favor for mishandling an expedition to the Azores. Banned from her sight after reaching for his sword in her presence, the hothead gallops to her palace in the early hours of the morning and challenges the guards to let him through chamber after chamber until he reaches the inner sanctum of the queen’s bed. There he sees her, without her wig, “her own sparse gray hair around her wrinkled face.” With that moment of truth, he guaranteed his own execution. It was a cruel codicil to the fantasy of courtly love.