There’s something undeniably ironic about a Supreme Court justice publishing a book defending the court as unflaggingly dedicated to its guiding principles and then, less than a year later, signing on to a dissent that explicitly lays out how “this court betrays its guiding principles.”

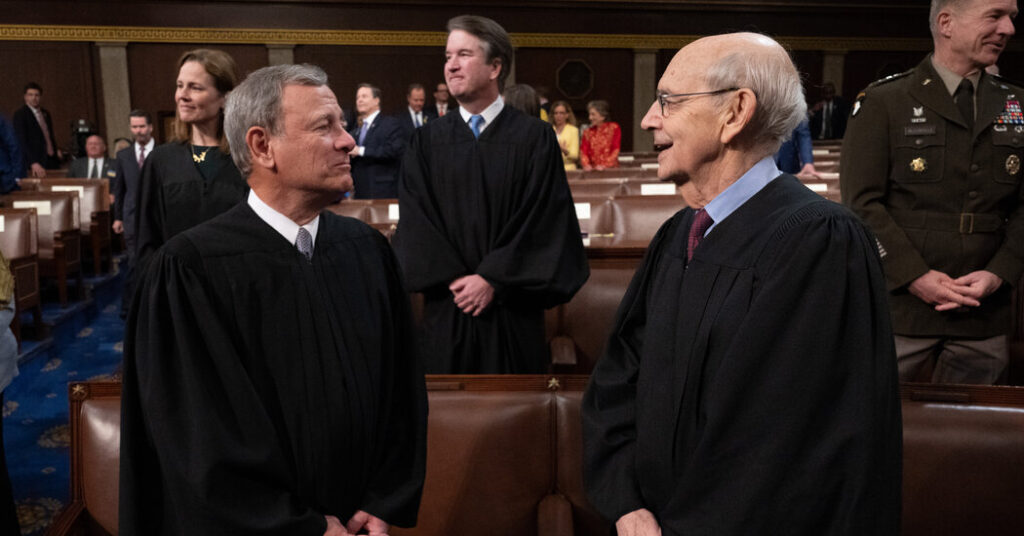

But then Justice Stephen G. Breyer, the author of the terribly timed “The Authority of the Court and the Peril of Politics,” which was published last September, has become a font of unintended irony. Last week, when the conservative majority on the Supreme Court handed down its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, effectively overturning Roe v. Wade and undoing a nearly 50-year-old constitutional right, it had been nine months — or 40 weeks and three days, to be exact — since Breyer’s treatise was born.

In an author’s note, Breyer mentions in passing that the book began as remarks for the 2021 Scalia Lecture at Harvard Law School. What he neglects to say is that the conservative Justice Antonin Scalia was known for exactly the kind of ideological reasoning whose very existence Breyer so assiduously tries to deny. “If I catch myself headed toward deciding a case on the basis of some general ideological commitment, I know I have gone down the wrong path, and I correct course,” Breyer writes. “My colleagues think the same way.”

The pugnacious Scalia was also known as a stylist, which Breyer decidedly is not; the lines in Breyer’s book are so unrelentingly bland that I began to wonder if the forgettable prose was deliberate — an attempt to steer clear of anything too sharp or intriguing, for fear of disrupting his careful tone of earnest sincerity. “The Authority of the Court” reads like what it is — an avuncular polemic constructed by an exemplary technocrat, blithely secure in the nobility of his intentions. In light of the Supreme Court’s recent bombshell decisions upending precedents on abortion rights and New York’s concealed-carry gun laws, the book takes on an added layer of unreality, as if Breyer brought a PowerPoint to a knife fight.

Parts of “The Authority of the Court” seem to be drawn from one of his earlier books, “Making Our Democracy Work,” published in 2010, in which he explained that respect for the rule of law was hard-won and shouldn’t be taken for granted. If you didn’t know any better, you wouldn’t get the sense from Breyer’s new book that much has changed in the last decade.

Donald J. Trump is mentioned only once, in a passage about Bush v. Gore, the 5-4 decision that effectively handed the 2000 election to George W. Bush. Some observers point to Bush v. Gore as a key event in the Supreme Court’s eroding legitimacy. Breyer waves away such criticisms, remarking proudly that “the court refused to hear or decide cases arising out of the 2020 election between Donald Trump and Joe Biden” — as if Gore’s request to continue counting votes in Florida and Trump’s command to overturn an election amount to basically the same thing.

Pointing to the fact that the Supreme Court sometimes rules in favor of conservative plaintiffs and sometimes rules in favor of liberal ones, Breyer says that “these inconsistencies convince me that it is wrong to think of the court as a political institution” — a sentence that exemplifies his reasoning. The Supreme Court cannot be political, he writes, because the justices aren’t political creatures; any of their disagreements arise from “jurisprudential differences.”

Yes, justices might have their own “views,” and there might be a political dimension to the nomination process, but Breyer insists that none of that truly matters: “My experience from more than 30 years as a judge has shown me that anyone taking the judicial oath takes it very much to heart. A judge’s loyalty is to the rule of law, not the political party that helped to secure his or her appointment.” OK, Breyer, if you say so.

The book is notably light on current specifics, glossing the thorny issue of “whether particular decisions are right or wrong” in favor of offering “general suggestions” about the importance of compromise and the need to “listen to others.” After recounting approvingly how Americans have become accustomed to accepting even those decisions they might vehemently disagree with, Breyer identifies “at least two threats that present cause for concern”: a growing distrust in government institutions and the way that journalists report on the courts. “What, then, can we do to stop the attrition of confidence?” One curious thing about Breyer’s argument is his insistence that the problem is somehow external to the Supreme Court itself — that the issue is one of observers’ “confidence,” not the institution’s own contributions to its crisis of legitimacy.

“The Authority of the Court” is so thinly supported that I had to wonder whether Breyer, who announced in January that he would retire after this term ends, conceived of this book as a last-gasp attempt to gently show his fellow justices how fragile trust in the court had become. Perhaps he believed that by declaring his faith in institutional integrity and judicial oaths, and studiously avoiding any overt conflicts, he might get them to recognize “the peril of politics” without resorting to unseemly alarm-ringing by a sitting judge.

It’s the only way that such a wan book by such a smart jurist makes any sense. It also accounts for a curious passage near the end, in which he quotes Albert Camus’s “The Plague” and compares the plague to … what? The novel was Camus’s allegory for the resistance to fascism. Breyer doesn’t come right out and say anything so incendiary, though he cryptically intones that “the rule of law is an important weapon, though not the only weapon, in our continuous fight against the plague germ.”

You have to wonder what Justice Clarence Thomas, who refused to recuse himself from hearing cases about an election that his wife sought to overturn, thinks about subtweets like this — if, that is, he’s had time to read Breyer’s book. After all, this Supreme Court, with Thomas comfortably ensconced in the conservative majority, has been keeping itself busy.

Reading Breyer’s book now, in the summer of 2022, also brings to mind a scene from a profile that ran in The New Yorker back in 2010. In it, the writer Jeffrey Toobin describes how he had visited Breyer in New Hampshire, where the justice has a log cabin, and the two men went out into the nearby pond in an old canoe.

“As we turned to head home, the blade of Breyer’s paddle broke off and sank,” Toobin writes, observing that Breyer seemed “unperturbed — indeed, barely noticing the disintegration of his equipment.” Luckily, they hadn’t ventured out too far; they were still near the shore instead of up a creek.

You may also like

-

Christian Cassarly: An Author’s Journey of Resilience, Inspiration, and Imagination

-

Unveiling the True Stories of Vietnam: An Interview with Doyle Glass, Author of “Swift Sword”

-

Breaking Barriers: Yuval Kanev’s ‘Helpless Earth: Reckless Science’ Provokes Urgent Dialogues on Technological Accountability

-

Astronomy for Teenagers: Galactic Odyssey – Inspiring Tales of Celestial Trailblazers

-

Books Over Bucks: Professor Aman’s Journey with First Book School