June Aochi Berk, now 92 years outdated, remembers the trepidation and worry she felt 80 years in the past on Jan. 2, 1945. On that date, Berk and her relations had been launched by army order from the U.S. authorities detention facility in Rohwer, Arkansas, the place that they had been imprisoned for 3 years due to their Japanese heritage.

“We didn’t celebrate the end of our incarceration, because we were more concerned about our future. Since we had lost everything, we didn’t know what would become of us,” Berk recollects.

The Aochis had been among the many almost 126,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry who had been forcibly faraway from their West Coast houses and held in desolate inland places below Government Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942.

Roughly 72,000, or two-thirds, of these incarcerated had been, like Berk, American-born residents. Their immigrant dad and mom had been authorized aliens, precluded by regulation from changing into naturalized residents. Roosevelt’s govt order and subsequent army orders excluding them from the West Coast had been based mostly on the presumption that folks sharing the ethnic background of an enemy could be disloyal to the USA. The federal government rationalized their mass incarceration as a “military necessity,” without having to convey fees towards them individually.

In 1983 a bipartisan federal fee discovered that the federal government had no factual foundation for that justification. It concluded that the incarceration resulted from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

President Ronald Reagan indicators the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 on Aug. 10, 1988, formally apologizing to People of Japanese descent who had been incarcerated throughout World Conflict II.

Densho Encyclopedia, CC BY-NC-SA

The fee suggestions resulted within the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Signed by President Ronald Reagan, the regulation offered surviving incarcerees with an apology for the unjustified authorities actions and token $20,000 funds. This laws and numerous judicial rulings have acknowledged that the incarceration was an egregious violation of U.S. constitutional ideas, a race-based denial of due course of.

No formal, complete information

A key aspect of this tragic and disgraceful chapter of American historical past is that no one ever stored monitor of all of the individuals who had been subjected to the federal government’s wrongful actions.

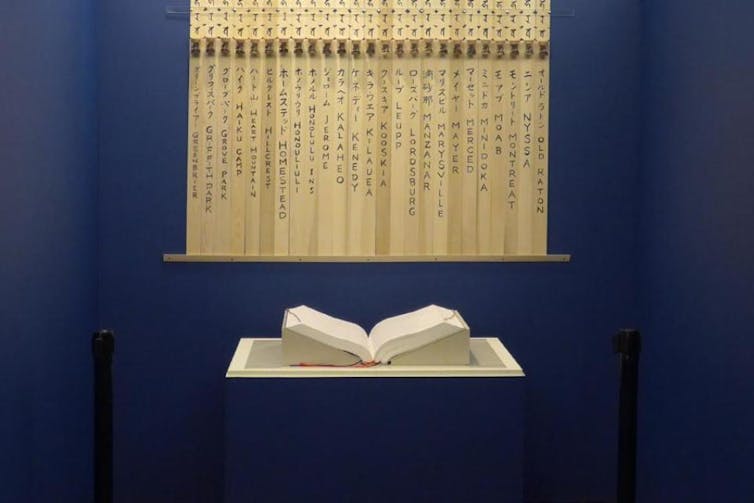

The Ireichō is in a particular house for guests to view.

Japanese American Nationwide Museum

To reckon with this injustice, the Irei Challenge: Nationwide Monument for the WWII Japanese American Incarceration was launched in 2019. This neighborhood nonprofit mission was initially incubated on the College of Southern California Shinso Ito Middle for Japanese Religions and Tradition, with a aim to create the first-ever complete listing of the names of each particular person incarcerated in America’s wartime internment and focus camps.

Taking the mission title “irei” from the Japanese phrase “to console the spirits of the dead,” the mission was impressed by stone Buddhist monuments that the detainees constructed whereas incarcerated in Manzanar, California, and Camp Amache, Colorado, to memorialize those that had died whereas wrongfully detained.

The phrase “approximately 120,000” incarcerees has typically been utilized by students, journalists and the Japanese American neighborhood as a result of the precise variety of these incarcerated has by no means been recognized. By creating an precise listing of names, the Irei Challenge has sought to verify an correct rely and to revive dignity to every one who skilled some constitutional injustice when the U.S. authorities decreased them to faceless enemies.

With the aim of leaving nobody out, a dozen part-time researchers on the Irei crew searched information within the Nationwide Archives and within the collections of different authorities establishments. Working with Ancestry.com and FamilySearch, Irei researchers have developed progressive methodologies and protocols to confirm identities, the locations of detention and, importantly, the correct spelling of names. Greater than 100 volunteers assembled and fact-checked the info.

As only one instance of creating certain the historic report is appropriate, a search by Nationwide Archive microfilm information revealed that “Baby Girl Osawa” was born to a mom incarcerated within the momentary detention facility often known as the Pomona Meeting Middle. Sadly, the newborn lived just a few hours.

Leaving nobody out signifies that this toddler is now among the many almost 6,000 further folks that the Irei Challenge has documented as amongst those that had been incarcerated. As of November 2024, the quantity is 125,761; because the analysis continues, the variety of documented incarcerees will proceed to develop.

As a 10-year-old, June Aochi Berk lived on this secure on the Santa Anita Racetrack.

Picture courtesy of June Aochi Berk

The ache of putting up with and remembering

With none means to return to their prewar neighborhood in Hollywood, California, the Aochis went to Denver, Colorado, the place buddies supplied to assist them get again on their ft. They and the opposite incarcerees girded themselves to face prejudice and hostile therapy that had solely intensified in the course of the conflict, to the purpose of terrorism.

“After the war, we just had to concentrate on restarting our lives, and we had to put the trauma of the incarceration behind us,” Berk defined.

For Berk, her fellow incarcerees and their descendants, the Irei Challenge supplies some acknowledgment of the lack of dignity suffered by people, households and communities.

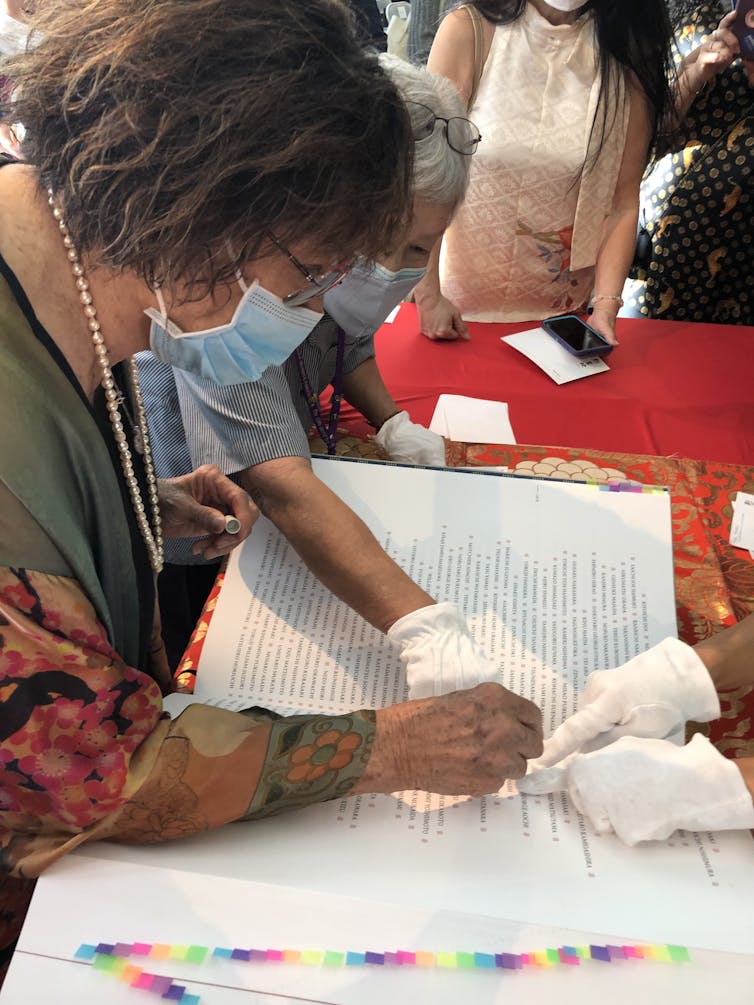

June Aochi Berk stamps subsequent to her dad and mom’ names within the Ireichō.

Picture courtesy of June Aochi Berk

“We were taught not to complain,” remembers Berk, “and yet it’s painful now to think about the endless ways in which we were mistreated. Do you know what it is like to be forced to live in a horse stable?”

Within the years following their incarceration, survivors would

typically cite how every incarcerated household was rendered anonymous when the federal government issued them a household quantity that supplanted their surname. Betty Matsuo, incarcerated at 16 and detained within the Stockton Meeting Middle and Rohwer Relocation Middle, informed the congressional fee, “I lost my identity. At that time, I didn’t even have a Social Security number, but the (War Relocation Authority) gave me an ID number. That was my identification. I lost my privacy and my dignity.”

For others, suppressing their anger, frustration and disgrace at being handled like a felony after they had not executed something flawed impaired their well being and relationships. Mary Tsukamoto, incarcerated at 27 and detained within the Fresno Meeting Middle and Jerome Relocation Middle, felt powerless after the conflict as the federal government actions had been constantly held up as justified, despite the fact that there was by no means any factual foundation for suspecting the Japanese American neighborhood of wholesale disloyalty. In 1986, she testified earlier than a congressional committee that for many years “we have lived within the shadows of this humiliating lie.” Tsukamoto thought it was necessary to “gain back dignity as a people who can all dream of a (n)ation that truly upholds the promise of … (j)ustice for (a)ll.”

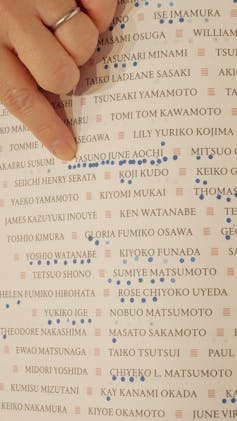

Stamped blue dots subsequent to June Aochi’s title characterize individuals who have visited the Ireichō to honor her.

Picture courtesy of June Aochi Berk

Therapeutic and reconciliation

To see the names of those that had been incarcerated in a ceremonial ebook known as the Ireichō, which implies “record of consoling spirits” in Japanese, is to acknowledge their struggling. The Ireichō has been on show for the previous two years on the Japanese American Nationwide Museum in Los Angeles.

Any member of the general public might make a reservation to put a blue dot stamp beneath the names, symbolically representing the Japanese custom of leaving stones at memorial websites. Though anybody might stamp names with none relationship to an incarceree, many surviving incarcerees have assembled their descendants and buddies collectively to stamp names of prolonged relations.

“The Ireichō has become an iterative form of a monument, drawing visitors as if they are pilgrims to a sacred site,” mentioned Ann Burroughs, the museum’s president and CEO.

Members of the Aochi household gathered in December 2024 to stamp June Aochi Berk’s title and people of her dad and mom within the Ireichō.

Picture courtesy of June Aochi Berk

Berk was one of many first to stamp the ebook, selecting to honor her dad and mom, Chujiro Aochi and Kei Aochi. “My parents set such a resilient example, and by paying this tribute to them, I am able to do something positive to help overcome all of the difficult memories,” Berk defined. For the neighborhood, every stamp is a small however significant act towards repairing the indignities suffered by every incarceree and reconciling with the previous.

Plans are for the Ireichō to go on a nationwide tour, with the aim of getting every title stamped at the least as soon as. Different elements of the Irei Challenge embrace the Ireizo, an interactive and searchable on-line archive, and the Ireihi, mild sculptures slated to be positioned at eight former World Conflict II confinement websites beginning in 2026.

On Dec. 1, 2024, Berk gathered her 5 kids and eight grandchildren with their companions to stamp her title and to put further stamps by the names of her dad and mom. She mentioned, “My children and grandchildren have a better understanding now of what happened to us during the war. This is a time of history we should never forget, lest our government ever takes such actions again and inflicts this painful experience upon any other person or group.”