VENICE — The 78 bronze funnels were ready, the pump tested and the backdrop was almost done. So when it looked as if war was most likely coming to Ukraine, Maria Lanko, one of the curators of the Ukrainian pavilion at the Venice Biennale, was determined to get the artist Pavlo Makov’s fountain sculpture safely out of the country.

In a recent interview in New York, Lanko described how she loaded the funnels in three boxes and packed them into her car. “We expected something might start,” she said. “There was a lot of tension and Putin gave us many hints.”

On the evening of the war’s first day, as explosions besieged the city, Lanko set off driving from Kyiv with her dog and a colleague, the pavilion’s art director, Sergiy Mishakin. “I started the journey without a precise route,” said Lanko. “I had to decide which road was safest.”

So began a harrowing three-week journey — driving 10 hours a day on back roads, staying in places without heat — that ultimately took Lanko out of Ukraine and to Vienna, where the sculpture’s materials were sent onward to Italy.

“It’s because of her that we are here now,” Makov said in an interview in Venice this month. “She took all these funnels and said, ‘We will do it anyway.’ And then we got to work and we did it,” he said.

It wasn’t quite that simple: Seventy-eight funnels do not, on their own, make a fountain. They needed to be fitted with modern hydraulics, and there were restrictions on installing those in the historic Arsenale where the work will be shown. With only weeks to go before the Biennale opening, the curators had to find a company that could assemble the structure in time.

Back in Kharkiv, in northeastern Ukraine, where he lives, Makov had considered staying put. But after days of bombings — and concerned about his 92-year-old-mother, who refused to leave her fourth-floor walk-up downtown — he decided to get his family to safety.

Makov; his wife; his mother; Tatiana Borzunova, the graphic designer of the pavilion’s catalog; her mother; and a cat all piled into his car, with only a few personal effects, choices dictated by the madness of the moment. “You open the drawers, and you think what will you take and you understand you don’t want to take anything,” he recalled. “I didn’t take anything. I left everything.”

They, too, headed for Venice via Vienna, where a home was found for the mothers.

Lanko, in the meantime, had found a company in Milan to create the fountain’s structure. It cost considerably more than she had budgeted, and she said the Biennale stepped up to pay for it.

“Maria can go through the wall if she needs it,” Makov said.

The structure arrived in Venice last week, just in time for the Biennale preview. The event opens to the public on Saturday, and runs through Nov. 27.

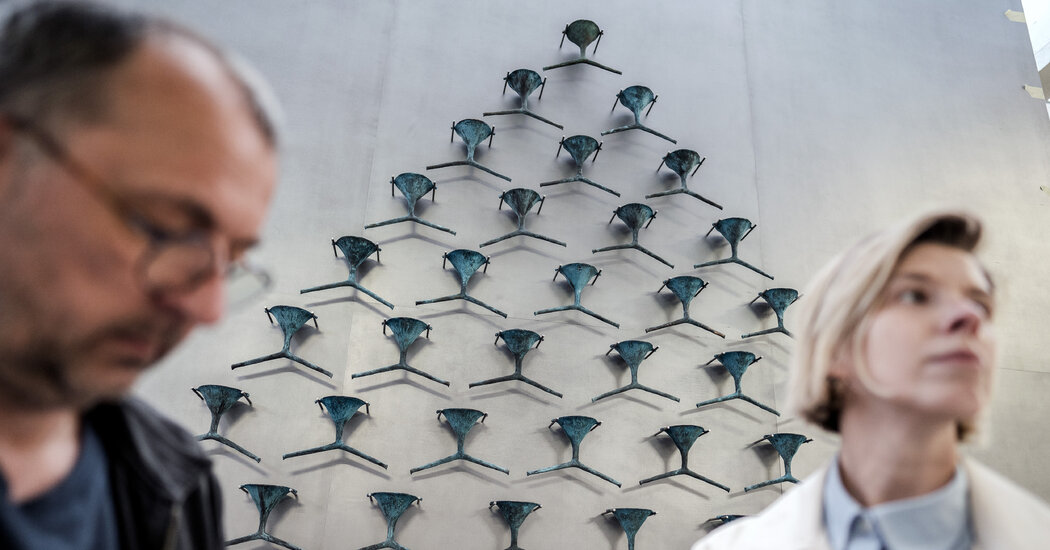

The installation for the Ukrainian pavilion — titled “Fountain of Exhaustion” — is an updated version of a sculpture Makov made in 1995.

It consists of an eight-foot pyramid of descending tiers of funnels, whose spouts feed water to the funnels below them. Water streams into the top funnel, but by the time it has arrived at the lowest tier, the flow has slowed to a trickle.

Makov had the idea for the fountain in 1994, he said. He had been inspired by the local situation in Kharkiv in the first difficult years after the collapse of the Soviet Union: “There was this lack of willpower in the society, this lack of vitality,” he said, that the city’s fountains, which weren’t working at the time, seemed to manifest.

The title of the work reflects “what I felt at the time,” he said.

He made other versions over the years. One, exhibited at the National Gallery in Kyiv in 2003, was bought by the Pinchuk Art Center, a private museum in the city, and a huge version incorporating over 200 funnels was shown in Lviv, in western Ukraine, in 2017.

With each iteration, its meaning broadened, to symbolize “the lack of vitality in Europe, and the exhaustion of humans in a democratic world,” Makov said.

And the message has metamorphosed once again with the Biennale installation.

“It connects to Venice, because the city is in a state of exhaustion,” Makov said: Take away the tourist industry, “and there is nothing left.” This version was a, “tribute to the city. It may be sad, but it is honest.”

The fragility of the watery city, engaged in a struggle against increasingly hostile elements, touches another chord, Makov said, “our exhaustion with our relationship with nature.”

How the Ukraine War Is Affecting the Cultural World

Valentin Silvestrov. Ukraine’s best-known living composer, Mr. Silvestrov made his way from his home in Kyiv to Berlin, where he is now sheltering. In recent weeks, his consoling music has taken on new significance for listeners in his war-torn country.

“Now we’re all concerned about the war, but three years ago, we were very much concerned about that fact that the ice is melting. And the ice is still melting, and in 10 years, it will still be melting,” he said. “We are failing to take responsibility for our relations with nature,” he said.

Since arriving in Venice a month ago, Makov said he has taken on the unexpected role of national spokesman. “I don’t feel myself an artist here, I feel much more a citizen of Ukraine, and that it’s my duty that Ukraine is represented at the Biennale,” he said.

Lanko said that this year’s Biennale was an important moment for Ukraine, the chance to showcase the country’s artistic talent and convey the message that a nation under siege can still make a creative contribution. “There is no knowledge about Ukrainian culture and art in the world,” she said. “It’s still considered to be part of the Russian cultural space. Being in places such as Venice, we can speak up with our art and our words.”

At the Giardini, the gardens where most large nations have their Biennale pavilions, Lanko has also realized an open-air installation called “Piazza Ucraina” along with the other curators of the Ukrainian Pavilion, Borys Filonenko and Lizaveta German.

The installation features a series of pillars that will be covered in posters, vetted by the curators, reflecting on the war. At the center, a mock-up of a monument covered by sandbags symbolizes Ukraine’s attempts to protect its heritage.

Roberto Cicutto, the Biennale’s president, said in a statement that it was “a space dedicated to Ukrainian artists and their resistance to the aggression” that “will help raise awareness in the world against the war and all that comes with it.”

Cecilia Alemani, curator of the Biennale’s main exhibition, said that throughout its 127-year existence, the event had “registered the shocks and revolutions of history like a seismographer. Our hope is that, with ‘Piazza Ucraina,’ we can create a platform of solidarity for the people of Ukraine in the earth of the Giardini.”

As long as the war continues, so will uncertainty; Makov said he wasn’t sure of what comes next. After the Biennale opens on Saturday, “there’s no plans whatsoever, and I decided not even to think about it. I will see,” he said.

Lanko said she hoped she could return to Kyiv soon. For now — even as she continues to worry about her family and friends back home — she is trying to focus on the positive: She made it to Venice with Makov’s work; the Ukrainian Pavilion will not stand empty. “I wake up, give myself an hour to cry, and then do things,” she said. “It was important to finally make it, despite the circumstances. Not everyone has the opportunity to leave Ukraine and to have a voice.”