Federal Reserve officials on Wednesday slowed their campaign to cool the economy but indicated that interest rates would rise higher in 2023 than previously expected as inflation proves more stubborn than policymakers had hoped.

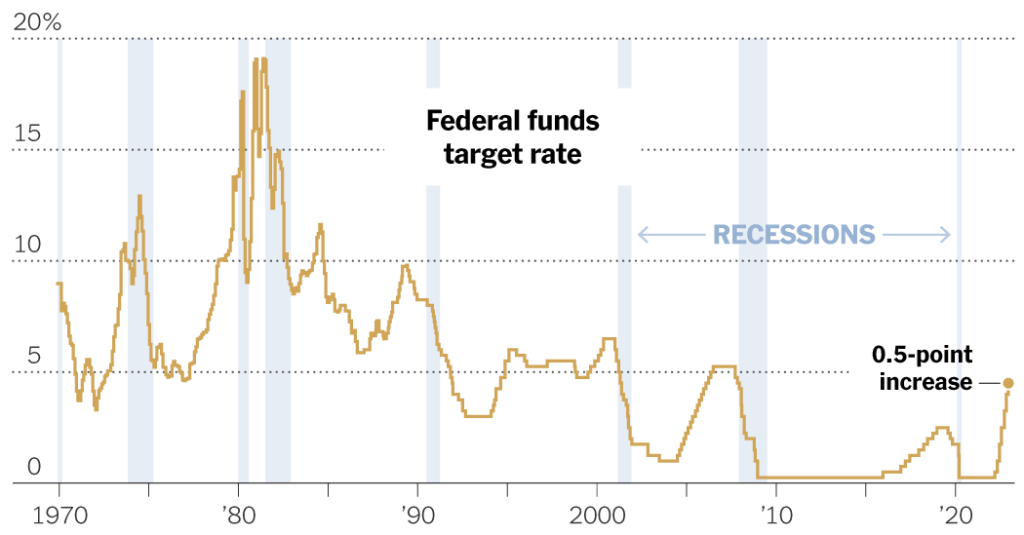

Fed officials voted unanimously at the conclusion of their two-day meeting to raise borrowing costs by half a percentage point, a pullback after four consecutive three-quarter point increases. Their policy rate is now set to a range of 4.25 to 4.5 percent, the highest it has been since 2007.

After months of moving rapidly to make money more expensive in an attempt to rein in an overheating economy, central bankers are entering a phase in which they expect to adjust policy more cautiously. That will give them time to see how the labor market and inflation are reacting to the policy changes they have already put in place.

Yet the Fed’s latest economic projections, released on Wednesday for the first time since September, sent a clear signal that slowing the pace of rate increases does not mean that officials are letting up in their battle against rapid inflation. Borrowing costs are expected to rise more drastically and inflict more economic pain than central bankers previously anticipated as policymakers attempt to wrangle stubborn price increases.

“We’ve continually expected to make faster progress on inflation than we have,” Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, said during his news conference after the release. He described the Fed’s new expectations as: “slower progress on inflation, tighter policy, probably higher rates, probably held for longer, just to get you to the kind of restriction that you need to get inflation down to 2 percent.”

Officials are now expecting to raise their policy interest rate to 5.1 percent by the end of 2023, which would mean another three-quarter-point worth of adjustments and would push it half a percentage point higher next year than officials previously anticipated. Policymakers also expect to keep borrowing costs higher for longer.

“We have more work to do,” Mr. Powell said.

The Fed’s higher rates are expected to cool the economy notably next year. Central bankers predict that unemployment will jump to 4.6 percent from 3.7 percent now, and then remain elevated for years. Growth is expected to be much weaker in 2023 than previously anticipated, pushing the economy to the brink of a recession.

“I don’t think anyone knows whether we’re going to have a recession or not, and if we do, whether it’s going to be a deep one or not,” Mr. Powell said. “It’s not knowable.”

The central bank’s aggressive stance comes as central bankers worry that inflation will remain high for years to come. Though price increases are already beginning to moderate from the four-decade highs they reached this summer, the Fed’s economic projections make clear that policymakers think it is going to take years to return inflation fully to their 2 percent goal.

Despite the tough talk from the Fed, investors on Wednesday seemed unconvinced. Stock prices in the S&P 500 fluctuated higher and lower as Mr. Powell spoke at a news conference before ending the day down 0.6 percent.

And though the Fed expects to keep rates above 5 percent through the end of 2023, investors are still betting that the central bank will stop raising rates sooner and begin cutting them earlier.

“Financial markets want black and white, and you’re working in shades of gray,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at KPMG, explaining that investors are not internalizing the Fed’s nuanced message.

That divergence could be a problem for central bankers. Higher stock prices and lower market-based interest rates make money cheaper and easier to borrow, helping to stimulate the economy — the opposite of the Fed’s goal as it tries to lower inflation.

“You hear the mantra, ‘Don’t fight the Fed,’ but at the moment the market is willing to fight the Fed,” said Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Amherst Pierpont Securities. “It’s an interesting dissonance that creates a risk for the market.”

Mr. Powell has repeatedly emphasized that his central bank is determined to keep fighting inflation until it is thoroughly vanquished, and on Wednesday he underlined that wrestling price pressures back under control is likely to take some time.

The Fed has recently received evidence that inflation is moderating, including in fresh Consumer Price Index data released Tuesday. Economists have spent months of waiting for rapid price increases in goods — from used cars to apparel — to slow as supply chains healed, which finally seems to be happening. Housing inflation is also poised to cool in 2023 as a recent slowdown in market-based rents shows up in official data, which should allow services inflation to begin to moderate.

But Mr. Powell said during his news conference that Fed officials need “substantially more evidence” to feel confident that inflation is on a sustained downward path.

In particular, a sharper economic deceleration may be needed for quick service price increases to fade fully. The job market is very strong and wages are growing rapidly, which could keep prices rising for things like haircuts, restaurant meals and financial help. That’s because as they pay their workers more, companies are likely to charge more to try to protect their profits.

“We do see a very, very strong labor market, one where we haven’t seen much softening,” Mr. Powell said. “Really there’s an imbalance in the labor market between supply and demand, so that part of it, which is the biggest part, is likely to take a substantial period to get down.”

Mr. Powell said, “That’s really why we’re writing down those high rates and why we’re expecting that they’ll have to remain high for a time.”

Even if the Fed can set the economy down relatively gently, officials expect their path to cause at least some pain in the labor market. While that is an unattractive prospect, central bankers believe it is necessary to prevent price increases from beginning to feed on themselves.

If consumers get used to rapid inflation and begin asking for bigger raises, and companies make bigger and more regular price adjustments to cover rising input and labor bills, fast price increases could become entrenched.

In the 1970s, officials allowed inflation to remain more rapid than usual for years on end, which created what economists have since called an “inflationary psychology.” When oil prices spiked for geopolitical reasons, an already elevated inflation base and high inflation expectations helped price increases to climb drastically. Fed policymakers ultimately raised rates to nearly 20 percent and pushed unemployment to double digits to bring prices back under control.

Officials today want to avoid a rerun of that painful experience. That’s why they have signaled that they do not want to give up on their fight against inflation too early.

“I wish there were a completely painless way to restore price stability,” Mr. Powell said. “There isn’t.”

You may also like

-

Public colleges report sharpest decline in tuition revenue since 1980

-

Unleashing the Future of Forex Trading: The Thrive FX Capital Revolution

-

Knife blunted: Some new versions of Swiss Army multi-tool will not have a blade

-

After Barstool Sports sponsorship fizzles, Snoop Dogg brand is attached to Arizona Bowl, fo shizzle

-

Warren Buffett says AI may be better for scammers than society. And he's seen how