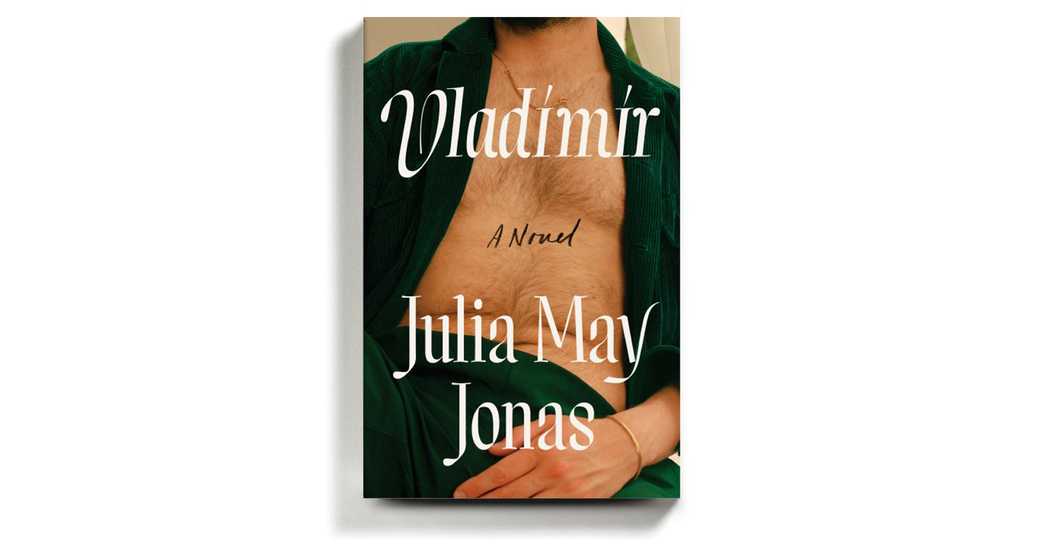

VLADIMIR

By Julia May Jonas

239 pages. Simon & Schuster. $27.

To read “Vladimir” (or any number of campus novels published in the past decade), you’d have to conclude that teaching humanities at the college level is pure hell. A person spends years in training only to land — if she’s lucky! — toiling for peanuts in a place where she never intended to live, drowning in administrative duties and serving at the pleasure of entitled and fickle students. To quote Peggy Lee: Is that all there is?

The thesis of Lee’s 1969 hit can be summarized as: Life is an unbroken series of disenchanting events, and the best solution is to “break out the booze and have a ball” with your friends. The unnamed narrator of Julia May Jonas’s debut novel, a 58-year-old literature professor at a college in upstate New York, adopts this philosophy of living.

We meet the narrator at a tough juncture. Her husband, John, is the chair of the school’s English department, and he’s in hot water for having relationships with students — relationships that occurred in the past, before the school explicitly banned such interactions, but details of which have recently surfaced and culminated in a petition signed by more than 300 people calling for his removal.

The narrator doesn’t care much about John’s dalliances. He’s more of a roommate than a husband, and the two have always had an agreement in which extramarital flings are tacitly permitted. What infuriates her are the women who have come forward. “I wish they could see themselves not as little leaves swirled around by the wind of a world that does not belong to them, but as powerful, sexual women interested in engaging in a little bit of danger, a little bit of taboo, a little bit of fun.” She finds their “post hoc prudery” nauseating.

This is a familiar situation by now: the (enraging to some, rightful to others) idea that past behavior might be punishable under newly imposed and unforeseen standards. But it is not what most interests Jonas.

She is more keen on examining the indignities of surviving a culture that viciously patrols female appetites of every kind: for sex, food, affection, happiness, power, professional recognition. The narrator begins by explaining her attraction to a “certain kind” of man — one who is “composed of desire,” who cannot imagine a “world that is not completely and totally guided by a sense of wanting and getting.” A man like her husband, in other words. But as John’s legal problems multiply, the narrator realizes that this construction of hedonistic masculinity may be on the verge of extinction.

Enter Vladimir Vladinski, a hot young experimental novelist and junior professor of literature. The narrator embarks on a course of seduction, getting anti-cellulite massages and a spray tan, dieting and exercising and monitoring her appearance with masochistic vigilance. Vladimir becomes not only a locus of long-suppressed horniness but also a tool of vengeance. The vengeance is directed specifically at her husband, and more generally at a world that denies women (especially of a certain age) the ecstasy of transgression.

The novel opens with Vladimir unconscious and shackled to a chair. How he arrived in this position, we don’t yet understand — but we know who put him there. In her narrator, Jonas has attempted to craft a woman of monstrous rapacity — someone in the tradition of Ruth in Fay Weldon’s “The Life and Loves of a She-Devil” or Undine Spragg in Edith Wharton’s “The Custom of the Country”: a character who forces us to question why qualities like excess and fury smell of villainy only when attached to women.

Among contemporary novelists, Lionel Shriver is the queen of these sour apple antiheroines. Her characters tend to be resentful, intelligent, picky, prickly and disdainful of weakness. They are also irresistible in a way that the narrator of “Vladimir” isn’t, perhaps because Jonas can’t quite persuade the reader of her professor’s reckless id.

Yes, she goes after Vladimir. Yes, she forcibly restrains him using a pair of zip ties that just happen to be at hand when she needs them. (Do most professors have zip ties hanging around?) But other than this one desperate act, she’s a sheep in wolf’s clothing. “I am the most selfish human being I know,” she remarks unconvincingly, given the novel’s ample evidence that she’s a forgiving spouse, a patient instructor and a considerate mother.

“My prey, my prize, my Vladimir,” she purrs upon capturing the younger man. But then she dithers. What seems like thrilling conviction dissolves into ambivalence. It’s hard to imagine Lady Macbeth or Annie Wilkes of “Misery” — literary sisters in monomania — pausing to take stock of their actions and thinking, as Jonas’s narrator does, “I simply needed some real food and to sleep — the excitement had taken too much out of this old girl.”

Jonas is an acidic observer of the body’s torments, and in dramatizing the perils of appetite she channels a story as potent (and ancient) as that of Adam and Eve. But what begins as an ode to transgression (yes, please!) takes a last-minute turn into an oddly conservative morality tale. The two transgressors of “Vladimir” find no artistic rewards or psychological freedom in their line-crossing. Instead, they wind up humiliated and maimed, while the afflicted parties remain safely ensconced in their institutions, apparently triumphant in victimhood.