Melvin Van Peebles was a lot of things — filmmaker, novelist, musician, playwright, painter, stock options trader, raconteur — but above all else, he was a showman, a masterful self-promoter and unapologetic huckster. When he died Tuesday at 89, he was a week from the release of the Criterion Collection’s new box set “Melvin Van Peebles: Essential Films” (available on Blu-ray Sept. 28), and Van Peebles, who always displayed a sharp sense of humor about himself and the world around him, might have appreciated the timing — his passing also served as one last act of ballyhoo for the man and his work.

“Essential Films” offers, as per usual for Criterion, a treasure trove of supplementary materials: audio commentaries, early short films, interviews, archival footage and the like. But the feature films collected in it — his first four, made in a remarkable burst of creativity between 1967 and 1973 — are the main attraction. As so many of the obituaries and tributes that have appeared this week give Van Peebles his (rightful) due as a cinematic maverick, an indie film groundbreaker and a Black film godfather, the Criterion set stands as a testament to his considerable skill, first and foremost, as a filmmaker. These four works display his technical prowess, social incisiveness and storytelling acumen. But most of all, they display his astonishing range.

He began, as most filmmakers do, by reflecting his influences. “The Story of a Three-Day Pass” was made in France, based on one of the novels he wrote there as an American abroad in the mid-1960s, and the fingerprints of the French new wave are all over it: a playful way with montage, a sense of visual humor and (especially) a deeply embedded sense of cool, as he shoots his hero, resplendent in his shades and fedora, strolling the streets of Paris like a Godard protagonist.

But as with most great filmmakers, those influences are a mere starter pistol, the fog from which Van Peebles’s own voice emerges — most important, in his exploration of the complexities and complications of Blackness. He writes his G.I. (played by Harry Baird), as a model soldier, and dramatizes his inner conflict with a series of scenes in which the G.I. is attacked by his own reflection in the mirror (“You’re the captain’s Uncle Tom,” the id figure snarls). The film’s most personal moments are its quietest, as his camera observes his protagonist as a man out of his element and out of his place, in a country where even the other Black people he encounters regard him with suspicion.

Van Peebles would follow those threads into his next film. The critical success of “The Story of a Three-Day Pass” landed him that most elusive of beasts, a deal with a mainstream studio, and the result was “Watermelon Man,” a tricky mash-up of high-concept comedy and social satire. The Black nightclub comedian Godfrey Cambridge stars, initially in whiteface, as a racist, self-satisfied insurance salesman who wakes up one morning and finds himself, inexplicably, Black from head to toe.

The stylistic shift between films is striking — this is a broader, sillier movie, swapping his debut’s jazzy score with wacky music cues, and its austere black-and-white photography for a supersaturated, suburban Day-Glo look. And Herman Raucher’s script works within traditional, setup-punchline comic rhythms — at first. But there’s real bite and real anger underneath, as the experience of being Black in America quickly (and unsurprisingly) radicalizes our central character, whose co-workers turn on him, whose neighbors harass him, and whose ostensibly liberal wife leaves him. The film ends with our hero embracing Black Power.

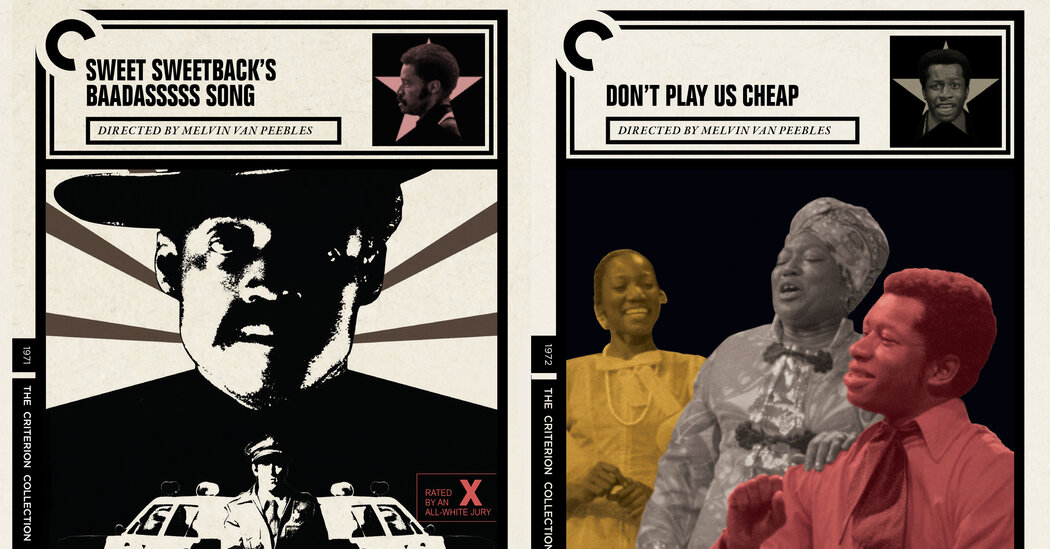

But its themes were timely, and sadly timeless: police brutality, institutional racism, media manipulation, sexual exploitation and stereotypes. The lowdown, homemade production (Van Peebles not only wrote and directed but also starred, edited and co-produced) crackled with a furious energy. Van Peebles keenly tapped into the moment’s post-Martin Luther King Jr. politics of racial radicalism, dedicating the film to “all the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of the Man,” and when it was rated X — usually the commercial kiss of death — he wore that designation in the advertising like a badge of honor, proclaiming his film was “Rated X by an all-white jury.”

The direct appeal worked, and “Sweet Sweetback” grossed more than $15 million (a spectacular return on its reported $500,000 budget). It’s also credited with helping kick off the so-called “blaxploitation” cycle — and Van Peebles could have easily participated in that commercially lucrative era, cranking out further crime pictures and revenge narratives. Instead, he went in an entirely opposite direction, following up “Sweet Sweetback” with “Don’t Play Us Cheap,” a film adaptation of one of his French novels.

Van Peebles wrote it as a musical comedy and rehearsed it like a Broadway show — and it ran there while he was editing the film version. So the film is an odd, rowdy fusion of performance document, movie musical and religious parable, filled with theatrical conventions (proscenium staging and lighting; big, boisterous performances; confessional ballads and high-spirited showstoppers) but also his signature cinematic flourishes.

The film was barely released in 1973; he wouldn’t direct another one until 1989. But in its own way, “Don’t Play Us Cheap” was as daring and out of the ordinary as “Sweet Sweetback” — another example of a filmmaker who refused to play by the rules, to do what was expected, to zig when he could zag. In many ways, the four Melvin Van Peebles works collected in the Criterion box have little in common: a French drama, a broad comedy, a ragged indie, a raucous musical. Yet every single film is undeniably his.