This article is part of the On Tech newsletter. Here is a collection of past columns.

Google and Facebook love to talk about the cutting-edge stuff that they’re working on. Metaverse! Driverless cars! Cloud! Artificial intelligence!

The reality, though, is that these tech companies are rich and powerful because they are the biggest sellers of advertising in the world. They do essentially the same thing that William Randolph Hearst did a century ago: They draw our attention to try to sell us yoga pants. (OK, Hearst’s newspapers probably didn’t have ads for leggings.)

There’s a vigorous public debate about the benefits and serious trade-offs of the digital worlds that Google and Facebook created. It’s less jazzy to think about digital advertising that these tech titans have popularized. But like everything else about these companies, it’s complicated and important.

Alphabet, the corporate entity that includes Google, made about 80 percent of its revenue this year from the ads that we see when searching the web, watching YouTube videos, checking out Google Maps and more. Facebook generated 98 percent of its revenue from ads. (Facebook likely won’t mention this today, when it plans to discuss the company’s vision of us living, shopping and working in its virtual reality world.)

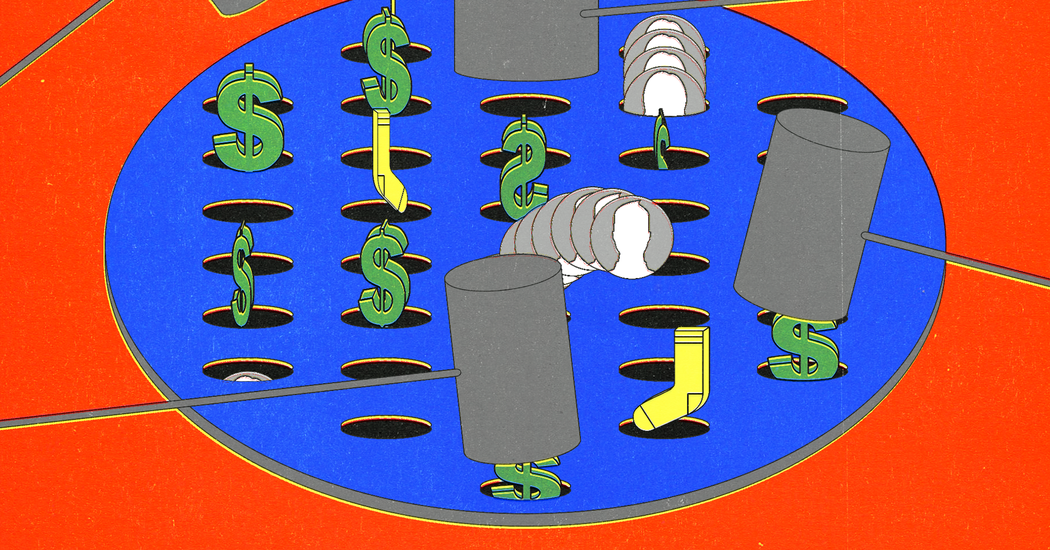

It’s not breaking news that Google and Facebook are souped-up versions of old-school advertising mediums like newspapers or radio. I am stressing the point for two reasons. First, zeroing in on their essence helps demystify those tech superpowers. Google and Facebook seem less mythical and imposing when you know that their empires are built on selling us more socks.

Second, I want us to think more about the warts-and-all effects of the Google and Facebook advertising powerhouses. The methods of advertising that the companies helped popularize — highly automated; based on information about who we are, what we do online and where we go; and at a scale unlike anything before — has changed the world around us in both good and harmful ways, without most of us really noticing.

Sure, some of the benefits are easy to see. Google and Facebook offer (arguably) helpful products and services at no cost to us, because advertising pays the bills. Ads also make stuff that we use outside Google and Facebook cheaper. Or possibly more expensive, which I’ll get to in a minute.

If you type “Miami vacations” into Google, that’s a blaring signal that you might be interested in booking a hotel room. If a hotel can pay an average of $1 per new customer for its website to show up prominently in those Google search results — versus spending $2 for each customer if it buys a television commercial — those hotel rooms might be cheaper for us.

That example is radically oversimplified, but you get the point. Even if you say that you hate ads or never use Facebook, the ads on these sites have beneficial ripple effects.

But there are also major drawbacks. To sell ads, Google and Facebook normalized the data arms race to collect as much information about us as possible, and now the bank, grocery store and weather apps are grubbing every detail they can to sell their own ads. Digital advertising also has a persistent problem with fraud and over promises that essentially impose a tax on everything that we buy.

The last thing I’ll mention is the perpetual motion machine of bigness. Google and Facebook are the biggest advertising sellers in the world largely because they are the largest gatherings of humans in the world. More people translate into more spots to sell ads.

That has created ripple effects for entertainment companies, newspapers and internet properties to try to merge or do anything they can to get bigger. I wonder if we would have a healthier economy and internet life if Comcast, TikTok and nearly every other company weren’t trying to amass the biggest audience of humans possible — partly to compete with Google and Facebook and sell more ads.

Understand the Facebook Papers

A tech giant in trouble. The leak of internal documents by a former Facebook employee has provided an intimate look at the operations of the secretive social media company and renewed calls for better regulations of the company’s wide reach into the lives of its users.

Tip of the Week

A new way for iPhone users to save a vaccine card

Brian X. Chen, the consumer technology columnist for The New York Times, is back with fresh advice on digital record keeping for Covid-19 vaccinations.

A few months ago, I shared a tip about how to securely store your digital vaccine card on your phone. As of this week, iPhone users now have a much simpler way to store their vaccine cards by adding the document to Apple’s Wallet app, its software that holds credit cards and important documents like travel itineraries.

Here’s how to set it up:

-

Download and install the latest software update for iOS (version 15.1). To do that, open the Settings app, tap General and then tap Software Update.

Before we go …

-

Never delete anything, I guess? Facebook told employees to preserve a wide range of internal documents and communications dating back to 2016, my colleagues Ryan Mac and Mike Isaac report. The company said that it did this in response to government inquiries stemming from the internal materials disseminated by Frances Haugen, a former Facebook product manager.

-

What a reality show teaches us about fame in the internet age: My colleague Amanda Hess has a thoughtful essay about a Hulu series featuring the TikTok-famous D’Amelio family, and the ways that social media is presented as a solution to mental health struggles.

-

What happens when people use coin-size Bluetooth tracking devices such as Apple’s AirTag to track their stolen cars or scooters? A Washington Post writer found out, including by following the theft of her 1999 Honda Civic. (A subscription may be required.)

Hugs to this

Does Swiss chard go with my wedding dress? A couple took their engagement photos at Berkeley Bowl, a grocery store in the Bay Area with rabid fans. (Our friends at the California Today newsletter wrote about this, too.)

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think of this newsletter and what else you’d like us to explore. You can reach us at ontech@nytimes.com.

If you don’t already get this newsletter in your inbox, please sign up here. You can also read past On Tech columns.